It's Lamkin was a mason good as ere built wi’ stane;

He built Lord Wearie's castle, but payment got he nane.

"O pay me, Lord Wearie, come, pay me my fee",

"I canna pay you, Lamkin, for I maun gang o'er the sea."

"O pay me now, Lord Wearie, come, pay me out o’ hand",

"I canna pay you, Lamkin, unless I sell my land."

"O gin ye winna pay me, I here sall mak a vow,

Before that ye come hame again, ye sall ha’e cause to rue."

Lord Wearie's got a bonny ship to sail the saut sea faem;

Bade his ladie weel the castle keep, ay till he should come hame.

But the nourice was a fause limmer as e’er hung on a tree;

She laid a plot wi' Lamkin, whan her lord was o’er the sea.

She laid a plot wi' Lamkin, whan the servants were awa',

Loot him in at a little shot-window an brought him to the ha'.

"O where's a' the men o' this house, that ca' me Lamkin?"

"They're at the barn-well thrashing; 'twill be lang ere they come in."

"O whare's the women o' this house, that ca' me Lamkin?"

"They're at the far well washing; 'twill be night or they come hame."

"An whare's the bairns o' this house, that ca' me Lamkin?"

"They're at the school reading; 'twill be night or they come hame."

"O whare's the lady o' this house, that ca’s me Lamkin?"

"Shee's up in her bower sewing, but we soon can bring her down."

Then Lamkin's tane a sharp knife that hang down by his gaire,

An he has gi’en the bonny babe a deep wound and a sair.

Then Lamkin he rocked, and the fause nourice sang,

Till frae ilka bore o' the cradle the red blood outsprang.

Then out it spak the lady, as she stood on the stair:

"What ails my bairn, nourice, that he's greeting sae sair?"

"O still my bairn, nourice, o still him wi' the pap!"

"He winna still, lady, for this nor for that."

"O still my bairn, nourice, o still him wi' the wand!"

"He winna still, lady, for a' his father's land."

"O still my bairn, nourice, o still him wi' the bell!"

"He winna still, lady, till ye come down yoursel."

O, the firsten step she steppit, shee steppit on a stane;

Bit the neisten step she steppit, she met him Lamkin.

"O mercy, mercy, Lamkin, hae mercy upon me!

Tho you've ta’en my young son's life, ye may let mysel be."

"O sall I kill her, nourice, or sall I let her be?"

"O kill her, kill her, Lamkin, for shee's ne’er was good to me."

"O scour the bason, nourice, an mak it fair an clean,

For to keep this lady's heart's blood, for she's come o' noble kin."

"There need nae bason, Lamkin, lat it run through the floor;

What better is the hart's blood o' the rich than o' the poor?"

But ere three months were at an end, Lord Wearie came again;

But dowie, dowie was his heart when first he came hame.

"O wha's blood is this?", he says, "that lies in my chamer?"

"It is your lady's heart's bluid; 'tis as clear as the lamer."

"An wha's blood is this", he says, "that lies in my ha'?"

"It is your young son's heart's blood; 'tis the cleirest ava. "

O sweetly sang the blackbird that sat upon the tree;

But sairer grat Lamkin, whan he was condemned to die.

An bonie sang the mavis, out o' the thorny brake;

Bit sairer grat the nourice, when she was tied to the stake.

He built Lord Wearie's castle, but payment got he nane.

"O pay me, Lord Wearie, come, pay me my fee",

"I canna pay you, Lamkin, for I maun gang o'er the sea."

"O pay me now, Lord Wearie, come, pay me out o’ hand",

"I canna pay you, Lamkin, unless I sell my land."

"O gin ye winna pay me, I here sall mak a vow,

Before that ye come hame again, ye sall ha’e cause to rue."

Lord Wearie's got a bonny ship to sail the saut sea faem;

Bade his ladie weel the castle keep, ay till he should come hame.

But the nourice was a fause limmer as e’er hung on a tree;

She laid a plot wi' Lamkin, whan her lord was o’er the sea.

She laid a plot wi' Lamkin, whan the servants were awa',

Loot him in at a little shot-window an brought him to the ha'.

"O where's a' the men o' this house, that ca' me Lamkin?"

"They're at the barn-well thrashing; 'twill be lang ere they come in."

"O whare's the women o' this house, that ca' me Lamkin?"

"They're at the far well washing; 'twill be night or they come hame."

"An whare's the bairns o' this house, that ca' me Lamkin?"

"They're at the school reading; 'twill be night or they come hame."

"O whare's the lady o' this house, that ca’s me Lamkin?"

"Shee's up in her bower sewing, but we soon can bring her down."

Then Lamkin's tane a sharp knife that hang down by his gaire,

An he has gi’en the bonny babe a deep wound and a sair.

Then Lamkin he rocked, and the fause nourice sang,

Till frae ilka bore o' the cradle the red blood outsprang.

Then out it spak the lady, as she stood on the stair:

"What ails my bairn, nourice, that he's greeting sae sair?"

"O still my bairn, nourice, o still him wi' the pap!"

"He winna still, lady, for this nor for that."

"O still my bairn, nourice, o still him wi' the wand!"

"He winna still, lady, for a' his father's land."

"O still my bairn, nourice, o still him wi' the bell!"

"He winna still, lady, till ye come down yoursel."

O, the firsten step she steppit, shee steppit on a stane;

Bit the neisten step she steppit, she met him Lamkin.

"O mercy, mercy, Lamkin, hae mercy upon me!

Tho you've ta’en my young son's life, ye may let mysel be."

"O sall I kill her, nourice, or sall I let her be?"

"O kill her, kill her, Lamkin, for shee's ne’er was good to me."

"O scour the bason, nourice, an mak it fair an clean,

For to keep this lady's heart's blood, for she's come o' noble kin."

"There need nae bason, Lamkin, lat it run through the floor;

What better is the hart's blood o' the rich than o' the poor?"

But ere three months were at an end, Lord Wearie came again;

But dowie, dowie was his heart when first he came hame.

"O wha's blood is this?", he says, "that lies in my chamer?"

"It is your lady's heart's bluid; 'tis as clear as the lamer."

"An wha's blood is this", he says, "that lies in my ha'?"

"It is your young son's heart's blood; 'tis the cleirest ava. "

O sweetly sang the blackbird that sat upon the tree;

But sairer grat Lamkin, whan he was condemned to die.

An bonie sang the mavis, out o' the thorny brake;

Bit sairer grat the nourice, when she was tied to the stake.

Contributed by CCG/AWS Staff - 2009/4/16 - 18:21

Language: Italian

Versione italiana di Riccardo Venturi (1993)

Da Child Ballads - Ballate popolari inglesi e scozzesi

Da Child Ballads - Ballate popolari inglesi e scozzesi

LAMBERTUCCIO

Lambertuccio era un bravo muratore, come nessuno sapeva lavorare;

Costruì il castello di Lord Wearie, ma lui non lo pagò.

"Pagami, Lord Wearie, pagami ciò che mi è dovuto",

"Non posso pagarti, Lambertuccio, ché devo andar per mare."

"Pagami ora, Lord Wearie, pagami della tua mano",

"Non posso pagarti, Lambertuccio, se non vendo le mie terre."

"Se tu non vuoi pagarmi, qui, adesso, faccio un voto:

Prima del tuo ritorno, io sarò la tua rovina."

Lord Wearie ha una bella nave per solcar la spuma del mare;

Disse alla sua signora di badare al castello fino al suo ritorno.

Ma la balia era una strega come mai avevan penduto da un albero;

Fece una tresca con Lambertuccio quando il padrone era per mare.

Fece una tresca con Lambertuccio quando la servitù non c'era,

Lo fece entrare da una postierla e lo portò nel castello.

"Dove sono gli uomini di casa, che mi chiamano Lambertuccio?"

"Sono a sarchiare il grano, e non torneranno presto."

"E dove sono le donne di casa, che mi chiamano Lambertuccio?"

"Sono lontano a lavare, e prima di sera non torneranno."

"E dove sono i bambini di casa, che mi chiamano Lambertuccio?"

"Sono a scuola a studiare, e prima di sera non torneranno."

"E dov'è la padrona di casa, che mi chiama Lambertuccio?"

"È a cucire nella sua stanza, presto la faremo scender giù."

Lambertuccio prese un coltello affilato che teneva al ginocchio,

Ha tirato una coltellata a quel bel bambino e l'ha ferito.

Lambertuccio lo cullava, la falsa balia cantava,

Finché il rosso sangue non sgorgò da ogni fessura della culla.

Allora esclamò la signora, mentre stava sulle scale:

"Cos'ha mio figlio, balia, ché piange così forte?

"Calma il bamnino, balia, calmalo con la poppa!"

"Non si calmerà, signora, per nessuna cosa al mondo."

"Calma il bambino, balia, calmalo con la bacchetta!"

"Non si calmerà, signora, per tutte le terre di suo padre."

"Calma il bambino, balia, calmalo col campanellino!"

"Non si calmerà, signora, finché tu non verrai giù."

Il primo passo che fece, lo fece sul pavimento;

Il secondo passo che fece, s'imbattè in Lambertuccio.

"Pietà, pietà, Lambertuccio! Abbi pietà di me!

Anche se hai ucciso mio figlio, lascia vivere me."

"La devo uccidere, balia, o la devo risparmiare?"

"Uccidila, Lambertuccio, non mi ha mai trattato bene."

"Lava il bacile, balia, puliscilo e fallo lucido,

Per tenerci il sangue della bella signora, che è di nobile casato."

"Non ce n'è bisogno, Lambertuccio, fallo colare per terra;

C'è forse differenza tra il sangue dei ricchi e dei poveri?"

E dopo tre mesi infine Lord Wearie tornò a casa;

Triste, triste era il suo cuore quando a casa ritornò.

"Di chi è questo sangue", chiede, "che c'è nella sua camera?"

"È il sangue di tua moglie, che è chiaro come l'ambra."

"E di chi è questo sangue", chiede, "che c'è nella mia sala?"

"È il sangue di tuo figlio, ed è il più chiaro di tutti."

E dolce cantava il merlo che se ne stava sull'albero;

Ma amaro piangeva Lambertuccio, quando fu messo alla forca.

E dolce cantava il tordo fuori dal cespuglio di spine;

Ma amaro piangeva la balia quando fu messa al rogo.

Lambertuccio era un bravo muratore, come nessuno sapeva lavorare;

Costruì il castello di Lord Wearie, ma lui non lo pagò.

"Pagami, Lord Wearie, pagami ciò che mi è dovuto",

"Non posso pagarti, Lambertuccio, ché devo andar per mare."

"Pagami ora, Lord Wearie, pagami della tua mano",

"Non posso pagarti, Lambertuccio, se non vendo le mie terre."

"Se tu non vuoi pagarmi, qui, adesso, faccio un voto:

Prima del tuo ritorno, io sarò la tua rovina."

Lord Wearie ha una bella nave per solcar la spuma del mare;

Disse alla sua signora di badare al castello fino al suo ritorno.

Ma la balia era una strega come mai avevan penduto da un albero;

Fece una tresca con Lambertuccio quando il padrone era per mare.

Fece una tresca con Lambertuccio quando la servitù non c'era,

Lo fece entrare da una postierla e lo portò nel castello.

"Dove sono gli uomini di casa, che mi chiamano Lambertuccio?"

"Sono a sarchiare il grano, e non torneranno presto."

"E dove sono le donne di casa, che mi chiamano Lambertuccio?"

"Sono lontano a lavare, e prima di sera non torneranno."

"E dove sono i bambini di casa, che mi chiamano Lambertuccio?"

"Sono a scuola a studiare, e prima di sera non torneranno."

"E dov'è la padrona di casa, che mi chiama Lambertuccio?"

"È a cucire nella sua stanza, presto la faremo scender giù."

Lambertuccio prese un coltello affilato che teneva al ginocchio,

Ha tirato una coltellata a quel bel bambino e l'ha ferito.

Lambertuccio lo cullava, la falsa balia cantava,

Finché il rosso sangue non sgorgò da ogni fessura della culla.

Allora esclamò la signora, mentre stava sulle scale:

"Cos'ha mio figlio, balia, ché piange così forte?

"Calma il bamnino, balia, calmalo con la poppa!"

"Non si calmerà, signora, per nessuna cosa al mondo."

"Calma il bambino, balia, calmalo con la bacchetta!"

"Non si calmerà, signora, per tutte le terre di suo padre."

"Calma il bambino, balia, calmalo col campanellino!"

"Non si calmerà, signora, finché tu non verrai giù."

Il primo passo che fece, lo fece sul pavimento;

Il secondo passo che fece, s'imbattè in Lambertuccio.

"Pietà, pietà, Lambertuccio! Abbi pietà di me!

Anche se hai ucciso mio figlio, lascia vivere me."

"La devo uccidere, balia, o la devo risparmiare?"

"Uccidila, Lambertuccio, non mi ha mai trattato bene."

"Lava il bacile, balia, puliscilo e fallo lucido,

Per tenerci il sangue della bella signora, che è di nobile casato."

"Non ce n'è bisogno, Lambertuccio, fallo colare per terra;

C'è forse differenza tra il sangue dei ricchi e dei poveri?"

E dopo tre mesi infine Lord Wearie tornò a casa;

Triste, triste era il suo cuore quando a casa ritornò.

"Di chi è questo sangue", chiede, "che c'è nella sua camera?"

"È il sangue di tua moglie, che è chiaro come l'ambra."

"E di chi è questo sangue", chiede, "che c'è nella mia sala?"

"È il sangue di tuo figlio, ed è il più chiaro di tutti."

E dolce cantava il merlo che se ne stava sull'albero;

Ma amaro piangeva Lambertuccio, quando fu messo alla forca.

E dolce cantava il tordo fuori dal cespuglio di spine;

Ma amaro piangeva la balia quando fu messa al rogo.

Language: English

Long Lankin

"When we were kids, the story of Long Lankin became somehow mixed up with that of Starlight Castle, the romantic ruins of which stand along Hollywell Dene, in Seaton Sluice, Northumberland.

The story we were told (and would indeed tell) was that at some pont in the mid 1700s, the notorious Sir Francis Delaval needed a home for one of his many concubines and so made a wager with a local stone-mason that if could build him a castle overnight, he would be paid thrice over the odds, but, should the mason fail, he would get nothing. Seemingly the mason made his task easier by having large sections of the castle prefabricated, so all that remained was to assemble these overnight, hence the name Starlight Castle. Hearing of this, however, Sir Francis called him a cheat and refused payment. In revenge, the mason brutally murdered the subsequent incumbent of the castle (whose ghost is said to haunt the spot to this day) for which crime the mason, who is remembered as Curry, was hung in a gibbet at a place on the nearby coast known to this day as Curry's Point.

There is historical fact here, as anyone will find out who Googles Delaval Starlight Castle, but the rest would appear to come wholesale from the ballad of Long Lankin - apart from the detail of Curry, who did indeed hang in a gibbet at Curry's Point, but for the murder of a local landlord some years before the building of Starlight Castle.

I must add that I knew the story long before ever I heard the ballad, so in my mind Long Lankin is forever associated with Starlight Castle, and Curry's Point with the dastardly mason therein. This is further complicated by assuming Starlight Castle was the ruins as depicted in this film, which is why I suggested that as the location rather than the actual Starlight Castle which does't have the right vibe."

Sedayne - From YouTube

The story we were told (and would indeed tell) was that at some pont in the mid 1700s, the notorious Sir Francis Delaval needed a home for one of his many concubines and so made a wager with a local stone-mason that if could build him a castle overnight, he would be paid thrice over the odds, but, should the mason fail, he would get nothing. Seemingly the mason made his task easier by having large sections of the castle prefabricated, so all that remained was to assemble these overnight, hence the name Starlight Castle. Hearing of this, however, Sir Francis called him a cheat and refused payment. In revenge, the mason brutally murdered the subsequent incumbent of the castle (whose ghost is said to haunt the spot to this day) for which crime the mason, who is remembered as Curry, was hung in a gibbet at a place on the nearby coast known to this day as Curry's Point.

There is historical fact here, as anyone will find out who Googles Delaval Starlight Castle, but the rest would appear to come wholesale from the ballad of Long Lankin - apart from the detail of Curry, who did indeed hang in a gibbet at Curry's Point, but for the murder of a local landlord some years before the building of Starlight Castle.

I must add that I knew the story long before ever I heard the ballad, so in my mind Long Lankin is forever associated with Starlight Castle, and Curry's Point with the dastardly mason therein. This is further complicated by assuming Starlight Castle was the ruins as depicted in this film, which is why I suggested that as the location rather than the actual Starlight Castle which does't have the right vibe."

Sedayne - From YouTube

LONG LANKIN

Said the lord unto his lady as he rode over the moss,

“Beware of Long Lankin that lives amongst the gorse.

Beware the moss, beware the moor, beware of Long Lankin.

Be sure the doors are bolted well lest Lankin should creep in.”

Said the lord unto his lady as he rode away,

“Beware of Long Lankin that lives amongst the hay.

Beware the moss, beware the moor, beware of Long Lankin.

Be sure the doors are bolted well lest Lankin should creep in.”

“Where's the master of the house?” says Long Lankin.

“He's away to London,” says the nurse to him.

“Where's the lady of the house?” says Long Lankin.

“She's up in her chamber,” says the nurse to him.

“Where's the baby of the house?” says Long Lankin.

“He's asleep in the cradle,” says the nurse to him.

“We will pinch him, we will prick him, we will stab him with a pin.

And the nurse shall hold the basin for the blood all to run in.”

So they pinched him, then they pricked him, then they stabbed him with a pin.

And the false nurse held the basin for the blood all to run in.

“Lady, come down the stairs,” says Long Lankin.

“How can I see in the dark?” she says unto him.

“You have silver mantles,” says Long Lankin,

“Lady, come down the stairs by the light of them.”

Down the stairs the lady came thinking no harm,

Lankin he stood ready to catch her in his arm.

There was blood all in the kitchen,

There was blood all in the hall.

There was blood all in the parlour

Where my lady she did fall.

Now Long Lankin shall be hanged

From the gallows oh so high.

And the false nurse shall be burned

In the fire close by.

Said the lord unto his lady as he rode over the moss,

“Beware of Long Lankin that lives amongst the gorse.

Beware the moss, beware the moor, beware of Long Lankin.

Be sure the doors are bolted well lest Lankin should creep in.”

Said the lord unto his lady as he rode away,

“Beware of Long Lankin that lives amongst the hay.

Beware the moss, beware the moor, beware of Long Lankin.

Be sure the doors are bolted well lest Lankin should creep in.”

“Where's the master of the house?” says Long Lankin.

“He's away to London,” says the nurse to him.

“Where's the lady of the house?” says Long Lankin.

“She's up in her chamber,” says the nurse to him.

“Where's the baby of the house?” says Long Lankin.

“He's asleep in the cradle,” says the nurse to him.

“We will pinch him, we will prick him, we will stab him with a pin.

And the nurse shall hold the basin for the blood all to run in.”

So they pinched him, then they pricked him, then they stabbed him with a pin.

And the false nurse held the basin for the blood all to run in.

“Lady, come down the stairs,” says Long Lankin.

“How can I see in the dark?” she says unto him.

“You have silver mantles,” says Long Lankin,

“Lady, come down the stairs by the light of them.”

Down the stairs the lady came thinking no harm,

Lankin he stood ready to catch her in his arm.

There was blood all in the kitchen,

There was blood all in the hall.

There was blood all in the parlour

Where my lady she did fall.

Now Long Lankin shall be hanged

From the gallows oh so high.

And the false nurse shall be burned

In the fire close by.

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2009/4/16 - 18:46

Questa versione è quella interpretata dagli "Steeleye Span" nel disco "Commoners Crown" nel 1975 con la voce di Maddy Prior.

Flavio Poltronieri - 2015/9/12 - 13:09

×

![]()

Note for non-Italian users: Sorry, though the interface of this website is translated into English, most commentaries and biographies are in Italian and/or in other languages like French, German, Spanish, Russian etc.

Child #93

Tradizionale inglese

English Traditional

[XII/XV sec./century ?]

Testo / Lyrics: Jamieson, I, 176

di Riccardo Venturi

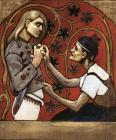

Poiché è compito e intento di questo sito proporre le “radici” di ogni suo argomento, andando a ritroso nelle tradizioni popolari di tutti i paesi, proponiamo qui questa terribile storia (Jamieson, I, 176; Child #93) che ci riporta ai tempi (circa tra il XII e il XV secolo) in cui i castelli dei nobili inglesi e scozzesi venivano costruiti da maestranze provenienti dalle Fiandre. Il nome del protagonista, Lamkin, sembra infatti essere il diminutivo fiammingo (Lambkijn, Lamkijn) di “Lambert”; anche se la sua assonanza con l'inglese “Lambkin”, ovvero “agnellino”, aggiunge un pizzico di tragica ironia a tutta la storia (e dal testo della ballata, appare chiaro che il protagonista è assai infastidito dall'essere chiamato in questo modo, e che è tutt'altro che un agnellino).

Una “vertenza sindacale”, la abbiamo chiamata: il punto di partenza della storia è infatti semplicissimo e consueto in tutte le epoche. Un lavoratore si spacca la schiena per costruire il bel castello al nobilastro di turno, in questo caso tale Lord Wearie, e giunto al momento di essere pagato gli viene risposto picche con una sequela di pretesti: il signor padrone “deve andare per mare”, “non ha soldi”, “deve vendere le terre”. Però, intanto, il castello se lo è fatto costruire. Nulla di più “moderno”, no? L'operaio lavora, e il padrone se ne va per gli affari suoi senza dargli un soldo.

Tempi assai rudi, quelli di Lamkin. Quando il padrone “se ne va per mare”, la questione viene risolta con una terrificante e spietata vendetta su due innocenti, la moglie e il figlio piccolo di Lord Wearie, massacrati senza pensarci due volte. Complice di Lamkin è la balia, dalla quale proviene un'altra interessante notizia: se infatti Lamkin ha dei dubbi nell'uccidere Lady Wearie, è proprio la balia che lo spinge infine a farlo perché l'altezzosa Lady (la quale sta implorando pietà e si guarda bene dal voler seguire la triste sorte del suo povero bambino) "non la aveva mai trattata bene".

Non è, questa, una ballata per stomachi deboli. Alla fine, dopo il classico rituale che, in un testo medievale, è pressoché d'obbligo (raccogliere il sangue di Lady Wearie in una bacinella d'argento per evitare che del sangue aristocratico coli sul pavimento, un'indegnità punita con il trasporto dell'anima all'inferno in un fiume di sangue; ma ancora una volta la balia interviene, spingendo Lamkin a non farne di nulla perché "il sangue dei ricchi è uguale a quello dei poveri", un'altra interessantissima affermazione in una ballata di tale antichità), Lamkin e la sua complice vengono messi, rispettivamente, alla forca e al rogo. Resta il motivo scatenante di tutta la spaventosa vicenda; la "guerra del lavoro" assume spesso le sembianze di una vera guerra.

Talmente scatenante, che rimane lo stesso anche nelle versioni più recenti trasportate nel Nuovo Mondo (particolarmente sull'isola di Terranova, nel New England e negli Stati del Sud e del Middle West): sempre un lavoratore che non viene pagato dal padrone. Ed anche in Scozia, vale a dire nella terra d'origine, Lamkin, a differenza di molti altri canti popolari oramai scomparsi, è stata udita anche in tempi piuttosto recenti, con il titolo di Long Lankin e probabilmente incrociata con la vicenda storica della costruzione del castello di Lord Delaval, Starlight Castle (avvenuta nel XVIII secolo). Ma con il titolo di Long Longkin si trova già nei Percy Papers. Scrive The Contemplator a proposito di "False Lamkin" (un altro titolo con cui è nota la ballata):È cantata tradizionalmente da un uomo (che interpreta il narratore, Lamkin e Lord Wearie) e da una donna (che interpreta Lady Wearie e la balia) su di un'aria molto grave e suggestiva, seppur rapida, drammatizzata in alcune strofe da un fiddle, sicuramente tra le più belle delle Child Ballads. La si può ascoltare in formato midi dal Contemplator. [RV]