Text von Joseph Wulf. Geschrieben 1943 in Oświęcim / Auschwitz III

זונענשטראַלן לײַכטן, װאַרמען, [1]

מענטשן־גופֿים קינד און אַלט,

און מיר דאׇ אײנגעשלאׇסן

אונדזער האַרץ איז דאׇך נישט קאַלט.

נשמות פֿלאַמען װי די זון אַלײן.

רײַסן, ברעכן טראׇץ דער פּײַן

װײַל עס פֿלאַטערט שױן אׇט די פֿאׇן

פֿון דער פֿרײַהײַט װאׇס קומט אׇן.

שנײַען װײַס פֿאַלן שטיל און זאַנפֿט

אױף די שװאַרצע װעלט װאׇס איז שלעכט.

און מיר דאׇ אײנגעשלאׇסן

װאַכן װי שטערנען אין די נעכט.

נשמות פֿלאַמען װי די זון אַלײן.

רײַסן, ברעכן טראׇץ דער פּײַן

װײַל עס פֿלאַטערט שױן אׇט די פֿאׇן

פֿון דער פֿרײַהײַט װאׇס קומט אׇן.

[1] Zunenshtraln laykhtn, varmen,

Mentshn-gufim kind un alt,

Un mir do ayngeshlosn

Undzer harts iz dokh nisht kalt.

Neshomes flamen vi di zun aleyn

Raysn, brekhn trots der payn

Vayl es flatert shoyn ot di fon

Fun der frayhayt vos kumt on.

Shnayen vays faln shtil un zanft

Oyf di shvartse velt vos iz shlekht.

Un mir do ayngeshlosn

Vakhn vi shternen in di nekht.

Neshomes flamen vi di zun aleyn

Raysn, brekhn trots der payn

Vayl es flatert shoyn ot di fon

Fun der frayhayt vos kumt on.

Mentshn-gufim kind un alt,

Un mir do ayngeshlosn

Undzer harts iz dokh nisht kalt.

Neshomes flamen vi di zun aleyn

Raysn, brekhn trots der payn

Vayl es flatert shoyn ot di fon

Fun der frayhayt vos kumt on.

Shnayen vays faln shtil un zanft

Oyf di shvartse velt vos iz shlekht.

Un mir do ayngeshlosn

Vakhn vi shternen in di nekht.

Neshomes flamen vi di zun aleyn

Raysn, brekhn trots der payn

Vayl es flatert shoyn ot di fon

Fun der frayhayt vos kumt on.

envoyé par CCG/AWS Staff - 4/3/2024 - 13:44

Langue: italien

Traduzione italiana / Italian translation / Traduction italienne / Italiankielinen käännös:

Riccardo Venturi, 4-3-2024 14:03

Riccardo Venturi, 4-3-2024 14:03

Raggi di sole

Raggi di sole illuminano e riscaldano

Corpi umani, vecchi e bambini.

E noi rinchiusi qua dentro,

Però il nostro cuore non è freddo.

Le anime ardono proprio come il sole,

Si spezzano, si rompono per la pena

Perché qui già sventola la bandiera

Della libertà che sta arrivando.

Bianche nevi cadono quiete e lievi

Sul nero mondo malvagio.

E noi, rinchiusi qua dentro,

Vegliamo come stelle nelle notti.

Le anime ardono proprio come il sole,

Si spezzano, si rompono per la pena

Perché qui già sventola la bandiera

Della libertà che sta arrivando.

Testo di Joseph Wulf. Scritta nel 1943 a Oświęcim / Auschwitz.

Raggi di sole illuminano e riscaldano

Corpi umani, vecchi e bambini.

E noi rinchiusi qua dentro,

Però il nostro cuore non è freddo.

Le anime ardono proprio come il sole,

Si spezzano, si rompono per la pena

Perché qui già sventola la bandiera

Della libertà che sta arrivando.

Bianche nevi cadono quiete e lievi

Sul nero mondo malvagio.

E noi, rinchiusi qua dentro,

Vegliamo come stelle nelle notti.

Le anime ardono proprio come il sole,

Si spezzano, si rompono per la pena

Perché qui già sventola la bandiera

Della libertà che sta arrivando.

Langue: anglais

English translation / Traduzione inglese / Traduction anglaise / Englanninkielinen käännös:

Riccardo Venturi, 4-4-2024 22:08

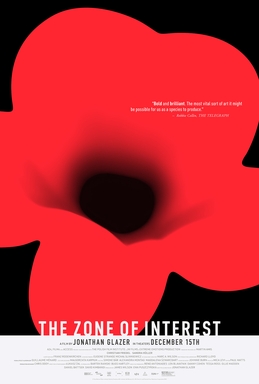

Translator’s note. This is a strictly literal translation of the song. In the motion picture The Zone of Interest, only a part of the song is heard while being played on the piano by the Polish young girl. There’s a rather free and artistic version of the verses in the subtitles, given here in a footnote.

Riccardo Venturi, 4-4-2024 22:08

Translator’s note. This is a strictly literal translation of the song. In the motion picture The Zone of Interest, only a part of the song is heard while being played on the piano by the Polish young girl. There’s a rather free and artistic version of the verses in the subtitles, given here in a footnote.

The song, and the Holocaust survivor, behind the year’s most stunning moment in film

How Joseph Wulf’s Yiddish song ‘Sunbeams,’ composed at Auschwitz, ended up in Jonathan Glazer’s ‘Zone of Interest’

Forward, Jewish Independent Nonprofit - PJ Grisar, December 19, 2023

The Zone of Interest, Jonathan Glazer’s drama about the humdrum home life of Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Höss, starts and ends with composer Mica Levi’s chorus of shrieking voices and synthesizers that lead the viewer in and out of the hell roiling just out of frame. The sound design as a whole — crowded with distant screams, gunshots and barking dogs — paints a picture of what the screen never dares show. But the film’s most arresting aural moment is a simple melody played on piano by a young Polish girl.

Before she plays, a voice speaking in Yiddish introduces the tune as the work of Joseph Wulf, written in 1944 in Auschwitz III. As the music starts, lyrics appear in subtitles: “Sunbeams, radiant and warm/Human bodies, young and old; And who are imprisoned here, Our hearts are yet not cold.” It is the film’s sole moment of direct Jewish testimony, and it is astonishingly voiceless. It was also, very nearly, forgotten.

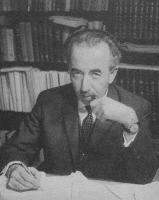

‘The Zone of Interest’ asks: Why would a family want to live at Auschwitz? Joseph Wulf, born in 1912 in Chemnitz and raised in Krakow, had a rabbinical education and was trained as an agronomist. His life changed course with the Nazi invasion. He and other Jews were restricted to the Krakow ghetto, where he knew the folk poet and songwriter Mordecai Gebirtig and painter Abraham Neumann. Wulf managed to escape and join the resistance but was captured in 1943 and deported to Buna-Monowitz, a subcamp of Auschwitz, for slave labor.

In the camp, Wulf vowed, if he survived, to commit his life to exposing Nazi crimes. As a member of the Jewish Historical Commission in Krakow after the war and a co-founder of the Centre for the History of Polish Jews in Paris, Wulf helped preserve the already famed work of Gebirtig and a lesser known composer named Jakub Weingarten. For all his diligence as a historian, Wulf didn’t rush to document his own songs from his time at Auschwitz.

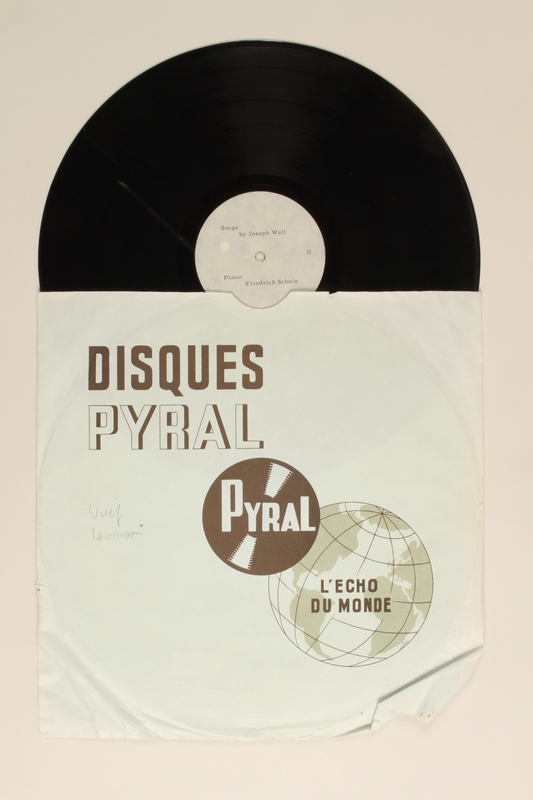

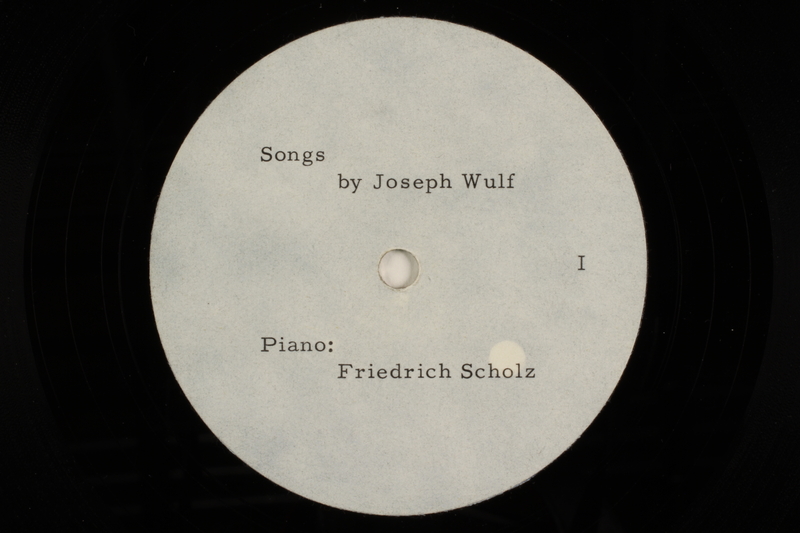

“They are extremely obscure,” said Bret Werb, the staff musicologist of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC. “He himself never did anything with them other than these home recordings.”

Around 2002, Werb found a reference to recordings Wulf made in the footnotes of a German dissertation. He wrote the author and learned the information came from a documentary by German journalist Henryk Broder, who had the tapes. Wulf, who organized singalongs for other laborers in the camps, recorded Hasidic melodies and songs by Gebirtig and Weingarten between 1966 and 1967 at a theater in West Berlin, accompanied by pianist Friedrich Schulz. He also taped two of his own, “Sunbeams” and a sentimental song about missing his wife. It is only through the recordings that we know the songs exist and have the audio of Wulf introducing and singing them. The voice heard in Zone of Interest was Wulf’s own.

“When he speaks the introduction, he’s like a dead man,” Werb said. “And then when he sings — he’s obviously not a professional singer — he’s not in tune or anything like that, but it’s so emotional.”

In July of 2021, Bridget Samuels, the music supervisor for The Zone of Interest, reached out to Werb looking for a piece of historical music. She wanted something that was from Auschwitz, in Yiddish and, preferably, unknown. Wulf’s song was the only thing that fit the bill. Werb says it’s an “unusual item,” in that a large percentage of music from the camps is in Polish, well known or had original words but a pre-existing melody.

There was a problem, however: the production needed a manuscript of the music for the scene. Most songs from the camps were unlikely to have been set down on paper.

“What they did was they made up these things and memorized them,” Werb said of inmates in the camps. “They didn’t write them down, and if they did write them down, they didn’t write the notes down.”

But, Werb was able to transcribe Wulf’s melody and the art department put together a prop — Werb found Wulf’s signature in a signed book to use on it — that looks authentic.

When we spoke, Werb hadn’t yet seen the film, for which he is credited, but was surprised by the context in which it was used. Its function, after many long scenes of the Höss family plundering the goods of prisoners — their lipstick, their perfume, even their false teeth — is to introduce a more abstract product of the camps: a mode of spiritual resistance we don’t see directly. Played on the piano by a young Polish girl, who found the music while planting fruit for the prisoners in the ditches where they dig, it is a radical expression of hope.

“We who are imprisoned here, are wakeful as the stars at night,” the subtitles read, as the piano plays under the unsounded words. “Souls afire, like the blazing sun, tearing, breaking through their pain, for soon we’ll see that waving flag, the flag of freedom yet to come.”

Wulf fled a death march in 1945 and spent decades as a historian chronicling, among other subjects, how Nazi ideology left its stamp on art. Settling in Germany in the 1950s, he published the first documentary works on the Holocaust in German and campaigned to have a research center devoted to the study of Nazism in Wannsee, where Nazi authorities solidified the Final Solution, but was met with resistance. (The museum he imagined came to be in 1992, and its library is named for him.)

On October 10, 1974, Wulf jumped from the window of his apartment in Berlin. A few months before his suicide, he had written to his son, despairing over how little impact his life’s work had on German academics, who, historians have since reasoned, believed his scholarship as a Jewish survivor to be biased.

“I have published 18 books about the Third Reich and they have had no effect. You can document everything to death for the Germans,” Wulf wrote. “There can be the most democratic government in Bonn – the mass murderers walk around free, live in their little houses, and grow flowers.”

As critic Jason Adams has noted, Wulf’s words could easily serve as a logline for Zone of Interest or a sequel set in the postwar period. But Rudolf Höss didn’t get to enjoy a long life after the war. He was hanged in 1947 in the last ever public execution in Poland after serving as a witness in Nuremberg; the evidence against him included an affidavit where Höss admitted to the “gassing and burning” of prisoners,.

While short on direct accounts of Höss’ crimes, the film hints that efforts like Wulf’s were not in vain. How strange, though, that it was a work Wulf never thought to publish, the melody and words he remembered, that will now serve as his best-known testimony.

How Joseph Wulf’s Yiddish song ‘Sunbeams,’ composed at Auschwitz, ended up in Jonathan Glazer’s ‘Zone of Interest’

Forward, Jewish Independent Nonprofit - PJ Grisar, December 19, 2023

The Zone of Interest, Jonathan Glazer’s drama about the humdrum home life of Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Höss, starts and ends with composer Mica Levi’s chorus of shrieking voices and synthesizers that lead the viewer in and out of the hell roiling just out of frame. The sound design as a whole — crowded with distant screams, gunshots and barking dogs — paints a picture of what the screen never dares show. But the film’s most arresting aural moment is a simple melody played on piano by a young Polish girl.

Before she plays, a voice speaking in Yiddish introduces the tune as the work of Joseph Wulf, written in 1944 in Auschwitz III. As the music starts, lyrics appear in subtitles: “Sunbeams, radiant and warm/Human bodies, young and old; And who are imprisoned here, Our hearts are yet not cold.” It is the film’s sole moment of direct Jewish testimony, and it is astonishingly voiceless. It was also, very nearly, forgotten.

‘The Zone of Interest’ asks: Why would a family want to live at Auschwitz? Joseph Wulf, born in 1912 in Chemnitz and raised in Krakow, had a rabbinical education and was trained as an agronomist. His life changed course with the Nazi invasion. He and other Jews were restricted to the Krakow ghetto, where he knew the folk poet and songwriter Mordecai Gebirtig and painter Abraham Neumann. Wulf managed to escape and join the resistance but was captured in 1943 and deported to Buna-Monowitz, a subcamp of Auschwitz, for slave labor.

In the camp, Wulf vowed, if he survived, to commit his life to exposing Nazi crimes. As a member of the Jewish Historical Commission in Krakow after the war and a co-founder of the Centre for the History of Polish Jews in Paris, Wulf helped preserve the already famed work of Gebirtig and a lesser known composer named Jakub Weingarten. For all his diligence as a historian, Wulf didn’t rush to document his own songs from his time at Auschwitz.

“They are extremely obscure,” said Bret Werb, the staff musicologist of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC. “He himself never did anything with them other than these home recordings.”

Around 2002, Werb found a reference to recordings Wulf made in the footnotes of a German dissertation. He wrote the author and learned the information came from a documentary by German journalist Henryk Broder, who had the tapes. Wulf, who organized singalongs for other laborers in the camps, recorded Hasidic melodies and songs by Gebirtig and Weingarten between 1966 and 1967 at a theater in West Berlin, accompanied by pianist Friedrich Schulz. He also taped two of his own, “Sunbeams” and a sentimental song about missing his wife. It is only through the recordings that we know the songs exist and have the audio of Wulf introducing and singing them. The voice heard in Zone of Interest was Wulf’s own.

“When he speaks the introduction, he’s like a dead man,” Werb said. “And then when he sings — he’s obviously not a professional singer — he’s not in tune or anything like that, but it’s so emotional.”

In July of 2021, Bridget Samuels, the music supervisor for The Zone of Interest, reached out to Werb looking for a piece of historical music. She wanted something that was from Auschwitz, in Yiddish and, preferably, unknown. Wulf’s song was the only thing that fit the bill. Werb says it’s an “unusual item,” in that a large percentage of music from the camps is in Polish, well known or had original words but a pre-existing melody.

There was a problem, however: the production needed a manuscript of the music for the scene. Most songs from the camps were unlikely to have been set down on paper.

“What they did was they made up these things and memorized them,” Werb said of inmates in the camps. “They didn’t write them down, and if they did write them down, they didn’t write the notes down.”

But, Werb was able to transcribe Wulf’s melody and the art department put together a prop — Werb found Wulf’s signature in a signed book to use on it — that looks authentic.

When we spoke, Werb hadn’t yet seen the film, for which he is credited, but was surprised by the context in which it was used. Its function, after many long scenes of the Höss family plundering the goods of prisoners — their lipstick, their perfume, even their false teeth — is to introduce a more abstract product of the camps: a mode of spiritual resistance we don’t see directly. Played on the piano by a young Polish girl, who found the music while planting fruit for the prisoners in the ditches where they dig, it is a radical expression of hope.

“We who are imprisoned here, are wakeful as the stars at night,” the subtitles read, as the piano plays under the unsounded words. “Souls afire, like the blazing sun, tearing, breaking through their pain, for soon we’ll see that waving flag, the flag of freedom yet to come.”

Wulf fled a death march in 1945 and spent decades as a historian chronicling, among other subjects, how Nazi ideology left its stamp on art. Settling in Germany in the 1950s, he published the first documentary works on the Holocaust in German and campaigned to have a research center devoted to the study of Nazism in Wannsee, where Nazi authorities solidified the Final Solution, but was met with resistance. (The museum he imagined came to be in 1992, and its library is named for him.)

On October 10, 1974, Wulf jumped from the window of his apartment in Berlin. A few months before his suicide, he had written to his son, despairing over how little impact his life’s work had on German academics, who, historians have since reasoned, believed his scholarship as a Jewish survivor to be biased.

“I have published 18 books about the Third Reich and they have had no effect. You can document everything to death for the Germans,” Wulf wrote. “There can be the most democratic government in Bonn – the mass murderers walk around free, live in their little houses, and grow flowers.”

As critic Jason Adams has noted, Wulf’s words could easily serve as a logline for Zone of Interest or a sequel set in the postwar period. But Rudolf Höss didn’t get to enjoy a long life after the war. He was hanged in 1947 in the last ever public execution in Poland after serving as a witness in Nuremberg; the evidence against him included an affidavit where Höss admitted to the “gassing and burning” of prisoners,.

While short on direct accounts of Höss’ crimes, the film hints that efforts like Wulf’s were not in vain. How strange, though, that it was a work Wulf never thought to publish, the melody and words he remembered, that will now serve as his best-known testimony.

Sunbeams [1]

Sunbeams light up and warm

Human bodies, old people and children.

And we are locked in here,

But our hearts are not cold.

Our souls burn just like the sun,

They tear, they break from pain

Because the flag is already waving here

Of the freedom that is to come.

White snows fall quietly and softly

On the black evil world.

And we, locked in here,

Watch like stars in the nights.

Our souls burn just like the sun,

They tear, they break from pain

Because the flag is already waving here

Of the freedom that is to come.

Lyrics by Joseph Wulf. Written 1943 in Oświęcim / Auschwitz III.

Sunbeams light up and warm

Human bodies, old people and children.

And we are locked in here,

But our hearts are not cold.

Our souls burn just like the sun,

They tear, they break from pain

Because the flag is already waving here

Of the freedom that is to come.

White snows fall quietly and softly

On the black evil world.

And we, locked in here,

Watch like stars in the nights.

Our souls burn just like the sun,

They tear, they break from pain

Because the flag is already waving here

Of the freedom that is to come.

[1] From the subtitles in the movie scene:

Sunbeams, radiant and warm,

Human bodies, young and old

And we, who are imprisoned here,

Our hearts are yet not cold.

We, who are imprisoned here

Are wakeful like starts at night

Souls afire, like the blazing sun

Tearing, breaking through their pain

For soon we’ll see the waving flag,

The flag of freedom yet to come.

Sunbeams, radiant and warm,

Human bodies, young and old

And we, who are imprisoned here,

Our hearts are yet not cold.

We, who are imprisoned here

Are wakeful like starts at night

Souls afire, like the blazing sun

Tearing, breaking through their pain

For soon we’ll see the waving flag,

The flag of freedom yet to come.

Langue: français

Version française – RAYONS DE SOLEIL – Marco Valdo M.I. – 2024

d’après la traduction italienne Raggi di sole – Riccardo Venturi – 2024

d’un poème en yiddish « זונענשטראַלן » - Zunenshtraln - de Joseph Wulf - 1943

Ce poème de Joseph Wulf a été écrit en 1943 à Oświęcim / Auschwitz III.

d’après la traduction italienne Raggi di sole – Riccardo Venturi – 2024

d’un poème en yiddish « זונענשטראַלן » - Zunenshtraln - de Joseph Wulf - 1943

RAYONS DE SOLEIL SUR LA VOIE

Edward Hopper – 1929

Edward Hopper – 1929

Ce poème de Joseph Wulf a été écrit en 1943 à Oświęcim / Auschwitz III.

RAYONS DE SOLEIL

Les rayons du soleil éclairent, réchauffant

Des corps humains, vieillards et enfants.

Et nous sommes enfermés là,

Mais nos cœurs ne sont pas froids.

Comme le soleil, les âmes brûlent ;

Elles se brisent, dans la douleur, elles se brisent,

Car ici le drapeau flotte déjà

De la liberté qui viendra.

Les neiges blanches tombent tranquilles et légères

Sur le monde noir et maléfique.

Et nous enfermés ici,

Nous veillons étoiles dans la nuit.

Comme le soleil, les âmes brûlent ;

Elles se brisent, dans la douleur, elles se brisent,

Car ici le drapeau flotte déjà

De la liberté qui viendra.

Les rayons du soleil éclairent, réchauffant

Des corps humains, vieillards et enfants.

Et nous sommes enfermés là,

Mais nos cœurs ne sont pas froids.

Comme le soleil, les âmes brûlent ;

Elles se brisent, dans la douleur, elles se brisent,

Car ici le drapeau flotte déjà

De la liberté qui viendra.

Les neiges blanches tombent tranquilles et légères

Sur le monde noir et maléfique.

Et nous enfermés ici,

Nous veillons étoiles dans la nuit.

Comme le soleil, les âmes brûlent ;

Elles se brisent, dans la douleur, elles se brisent,

Car ici le drapeau flotte déjà

De la liberté qui viendra.

envoyé par Marco Valdo M.I. - 4/3/2024 - 20:43

Langue: allemand

Deutsche Version / Versione tedesca / German version / Version allemande / Saksankielinen versio:

Riccardo Venturi, 5-3-2024 19:41

Riccardo Venturi, 5-3-2024 19:41

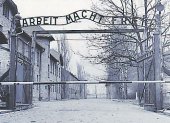

Rudolf Höß war der Schöpfer des berüchtigten Slogans an den Toren von Auschwitz.

Sonnenstrahlen leuchten und wärmen

Menschenkörper, Greise und Kinder.

Und wir sind hier eingesperrt,

Unser Herz ist doch nicht kalt.

Seelen brennen wie die Sonne,

Reißen, brechen durch ihren Schmerz,

Denn schon flattert hier die Flagge

Der ankommenden Freiheit.

Weisser Schnee fällt still und sanft

Auf die schwarze böse Welt.

Und wir sind hier eingesperrt,

Wachen wie Sterne in der Nacht.

Seelen brennen wie die Sonne,

Reißen, brechen durch ihren Schmerz,

Denn schon flattert hier die Flagge

Der ankommenden Freiheit.

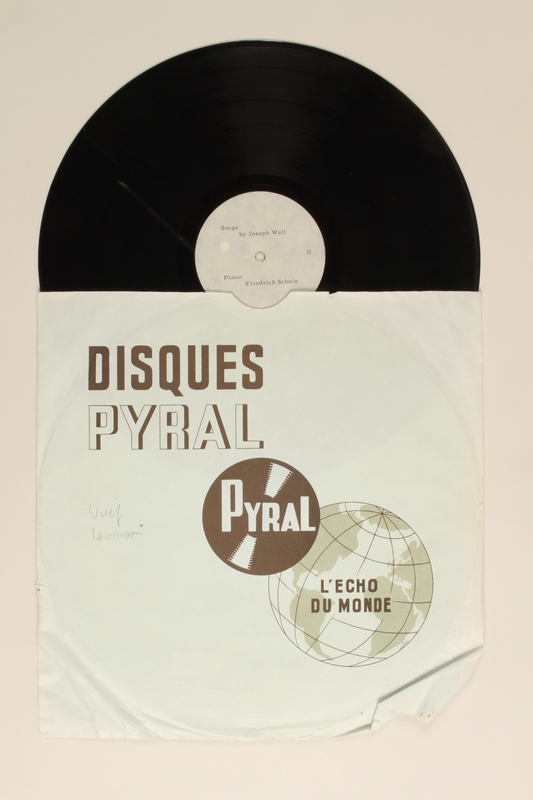

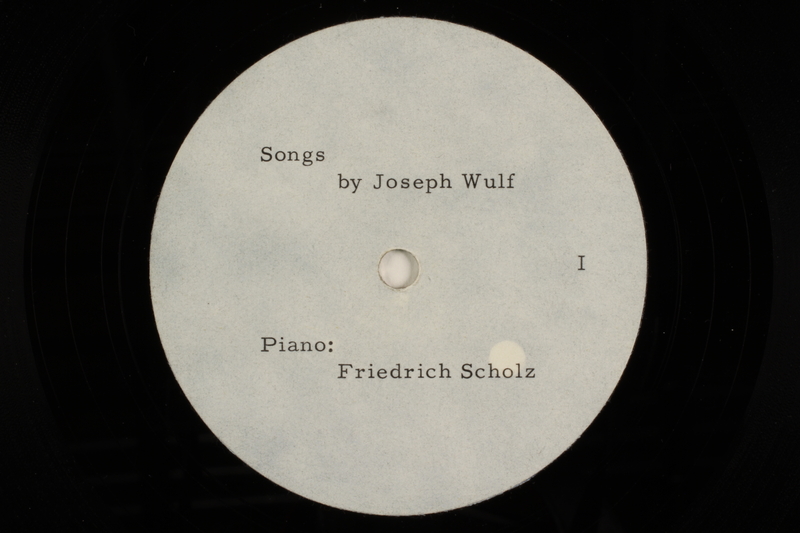

Songs by Joseph Wulf

Dysques Pyral - L'écho du monde

Paris ca. 1950

Dysques Pyral - L'écho du monde

Paris ca. 1950

Riccardo Venturi - 4/3/2024 - 23:18

Nel film la canzone è solo strumentale. La ragazza polacca ritrova fortunosamente lo spartito e suona la melodia al pianoforte. Le parole tradotte liberamente appaiono nei sottotitoli.

Lorenzo - 4/3/2024 - 23:49

Io, invece, ho corretto un verso che avevo capito male: da Shnayen vays farshtiln un zamn a Shnayen vays faln shtil un zanft "bianche nevi cadono quiete e lievi [leggere / morbide ecc.]". Di conseguenza, ho adattato tutte le traduzioni presenti nella pagina. Mi scuso per questo fraintendimento.

Riccardo Venturi - 5/3/2024 - 02:16

"We stand here as men who refute their Jewishness and the Holocaust being hijacked by an occupation which has led to conflict, for so many innocent people.”

'Zone of Interest' director Jonathan Glazer spoke out about Israel's weaponisation of the Holocaust in his Oscar acceptance speech.

La zona di interesse e la musica del genocidio. Un immenso grazie per tutte queste informazioni a Riccardo.

Aggiungo questo link che racconta il lavoro per la creazione della colonna sonora

Aggiungo questo link che racconta il lavoro per la creazione della colonna sonora

La colonna sonora de La zona d’interesse è di un livello altissimo. Tapparsi le orecchie non è un’opzione possibile

È il suono del genocidio programmato. La ricerca sonora di Johnnie Burn e lo score vertiginoso di Mica Levi ci tengono in tensione, incollati alla seduta e ci fanno chiedere come sia (stato) possibile accettare questo orrore. Dal 22 febbraio al cinema.

Paolo Rizzi - 14/3/2024 - 13:28

Paolo Rizzi - 14/3/2024 - 13:33

×

![]()

[1943]

Testo e musica / Lyrics and music / Paroles et musique / Sanat ja sävel: Joseph Wulf

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, gift of Henryk M. Broder

From the Joseph Wulf phonograph records collection that Henryk M. Broder

donated to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 2002.

Piano: Friedrich Scholz (1926-2008)

Disques Pyral, ca. 1950

Nel 1943, Joseph Wulf, ebreo germano-polacco nato a Chemnitz nel 1912, è prigioniero a Auschwitz III (il sottocampo di Buna-Monowitz). Lui e la sua famiglia erano stati deportati dal ghetto di Cracovia, dove erano diventati amici di Mordechai Gebirtig e del pittore Abraham Neumann. Joseph Wulf era un perito agrario ed un esperto in studi ebraici (tanto che la famiglia voleva farne un rabbino). Joseph Wulf si unì al movimento partigiano ebraico; una volta deportato, decise di dedicare la vita alla rivelazione e alla denuncia, con ogni mezzo possibile, dei crimini nazisti. Sopravvissuto alla deportazione e alle “marce della morte” (assieme alla moglie e al giovanissimo figlio; tutto il resto della famiglia perì nel campo), nel dopoguerra fondò la Commissione Storica Ebraica a Cracovia, e fu cofondatore del Centro Storico degli Ebrei Polacchi a Parigi; e fu proprio a Parigi, circa nel 1950, che registrò una serie di canzoni in lingua yiddish, soprattutto per preservare le opere di Mordechai Gebirtig e Jakub Weingarten; ma aveva scritto personalmente anche un paio di canzoni, che ugualmente registrò facendosi accompagnare al pianoforte dal compositore Friedrich Scholz; tra di esse, Zunenshtraln (“Raggi di sole”), che avrebbe avuto in sorte di diventare famosa ottant’anni dopo, grazie a un film.

Il film è La zona d’interesse (The Zone of Interest, 2023) di Jonathan Glazer, presentato in concorso al festival di Cannes del 2023 (dove ha ottenuto il Grand Prix) e che è attualmente candidato a 5 Oscar. Verso la fine del film, una bambina polacca suona al piano una canzone al piano: è Zunenshtraln. Durante la decennale realizzazione del film (nel quale l’orrore che si svolge accanto all’idilliaca tenuta del direttore di Auschwitz, Rudolf Höß, la “zona di interesse” -Interessengebiet di 25 chilometri quadrati che dà il titolo al film, viene tenuto nascosto alla famiglia, e soltanto udito), Jonathan Glazer cercava specificamente una canzone scritta nel campo, rimasta pressoché sconosciuta. La trovò presso lo United States Holocast Memorial Museum, scritta e interpretata dal suo autore (che, nella registrazione, la introduce brevemente in tedesco). Nonostante Joseph Wulf sia stato tra i primissimi ad aver testimoniato direttamente degli orrori di Auschwitz, le sue canzoni (assieme a tutte le altre di Mordechai Gebirtig, da lui registrate) sono rimaste del tutto ignote fino al 2002, quando Henryk M. Broder donò tutto il materiale in suo possesso al museo americano. Joseph Wulf, pur avendo dedicato tutto il resto della sua vita alla testimonianza, era rimasto sempre molto scettico riguardo al suo reale impatto: soleva infatti dire di “avere scritto 18 libri sulla tragedia di Auschwitz, che non sono serviti a nulla”. Il 10 ottobre 1974, si suicidò gettandosi da una finestra del suo appartamento berlinese.

Le ricerche di Jonathan Glazer sembrano comunque essere state indirizzate da una donna, di nome Alexandria, che il regista aveva incontrato durante le lunghissime riprese del film. Questa donna, che all’età di 12 anni era membro della resistenza polacca, era solita recarsi a raccogliere mele per lasciarle di nascosto ai prigionieri che morivano di fame. Fu lei a scoprire la canzone scritta da Joseph Wulf. Alexandria aveva 90 anni quando incontrò Joseph Glazer, e morì poco dopo. Joseph Wulf, la moglie e il figlio fuggirono da Auschwitz il 18 gennaio 1945, poco dopo essere sopravvissuti a una “marcia della morte”; furono nascosti ed aiutati da una famiglia di contadini polacchi.

Con il film di Jonathan Glazer, la canzone di Joseph Wulf è salita alla ribalta mondiale. Di essa si trovava oramai tutto: registrazione, dati e una parzialissima e libera versione in inglese (tratta dai sottotitoli del film, relativamente ai versi che vi si sentono cantati in yiddish). Tutto, tranne -naturalmente- il testo: assolutamente impossibile reperirlo, se mai sia esistito da qualche parte in rete o altrove. Abbiamo quindi deciso di trascriverlo all’ascolto diretto dalla registrazione messa a disposizione dal Museo dell’Olocausto degli Stati Uniti d’America (Accession Number: 2002.190 | RG Number: RG-91.0107 ). Con questo speriamo di aver messo a disposizione un documento importante, realizzando anche un video. [RV]