As it befell upon one time,

About mid-summer of the year,

Every man was taxt of his crime,

For stealing the good Lord Bishop's mare.

The good Lord Screw he sadled a horse,

And rid after this same scrime;

Before he did get over the moss,

There was he aware of Sir Hugh of the Grime.

'Turn, O turn, thou false traytor,

Turn, and yield thyself unto me;

Thou hast stolen the Lord Bishops mare,

And now thou thinkest away to flee.'

'No, soft, Lord Screw, that may not be!

Here is a broad sword by my side,

And if that thou canst conquer me,

The victory will soon be try'd.'

'I ner was afraid of a traytor bold,

Although thy name be Hugh in the Grime;

I'le make thee repent thy speeches foul,

If day and life but give me time.'

'Then do thy worst, good Lord Screw,

And deal your blows as fast as you can;

It will be try'd between me and you

Which of us two shall be the best man.'

Thus as they dealt their blows so free,

And both so bloody at that time,

Over the moss ten yeomen they see,

Come for to take Sir Hugh in the Grime.

Sir Hugh set his back against a tree,

And then the men encompast him round;

His mickle sword from his hand did flee,

And then they brought Sir Hugh to the ground.

Sir Hugh of the Grime now taken is

And brought back to Garlard town;

[Then cry'd] the good wives all in Garlard town,

'Sir Hugh in the Grime, thou 'st ner gang down.

'

The good Lord Bishop is come to the town,

And on the bench is set so high;

And every man was taxt to his crime,

At length he called Sir Hugh in the Grime.

'Here am I, thou false bishop,

Thy humours all to fulfill;

I do not think my fact so great

But thou mayst put it into thy own will.'

The quest of jury-men was calld,

The best that was in Garlard town;

Eleven of them spoke all in a breast,

'Sir Hugh in the Grime, thou 'st ner gang down.

'

Then another questry-men was calld,

The best that was in Rumary;

Twelve of them spoke all in a breast,

'Sir Hugh in the Grime, thou'st now guilty.'

Then came down my good Lord Boles,

Falling down upon his knee:

'Five hundred peices of gold would I give,

To grant Sir Hugh in the Grime to me.'

'Peace, peace, my good Lord Boles,

And of your speeches set them by!

If there be eleven Grimes all of a name,

Then by my own honour they all should dye.'

Then came down my good Lady Ward,

Falling low upon her knee:

'Five hundred measures of gold I'le give,

To grant Sir Hugh of the Grime to me.'

'Peace, peace, my good Lady Ward,

None of your proffers shall him buy!

For if there be twelve Grimes all of a name,

By my own honour they all should dye.'

Sir Hugh of the Grime's condemnd to dye,

And of his friends he had no lack;

Fourteen foot he leapt in his ward,

His hands bound fast upon his back.

Then he lookt over his left shoulder,

To see whom he could see or spy;

Then was he aware of his father dear,

Came tearing his hair most pittifully.

'Peace, peace, my father dear,

And of your speeches set them by!

Though they have bereavd me of my life,

They cannot bereave me of heaven so high.'

He lookt over his right shoulder,

To see whom he could see or spye;

There was he aware of his mother dear,

Came tearing her hair most pittifully.

'Pray have me remembred to Peggy, my wife;

As she and I walkt over the moor,

She was the cause of [the loss of] my life,

And with the old bishop she plaid the whore.

'Here, Johnny Armstrong, take thou my sword,

That is made of the mettle so fine,

And when thou comst to the border-side,

Remember the death of Sir Hugh of the Grime.

About mid-summer of the year,

Every man was taxt of his crime,

For stealing the good Lord Bishop's mare.

The good Lord Screw he sadled a horse,

And rid after this same scrime;

Before he did get over the moss,

There was he aware of Sir Hugh of the Grime.

'Turn, O turn, thou false traytor,

Turn, and yield thyself unto me;

Thou hast stolen the Lord Bishops mare,

And now thou thinkest away to flee.'

'No, soft, Lord Screw, that may not be!

Here is a broad sword by my side,

And if that thou canst conquer me,

The victory will soon be try'd.'

'I ner was afraid of a traytor bold,

Although thy name be Hugh in the Grime;

I'le make thee repent thy speeches foul,

If day and life but give me time.'

'Then do thy worst, good Lord Screw,

And deal your blows as fast as you can;

It will be try'd between me and you

Which of us two shall be the best man.'

Thus as they dealt their blows so free,

And both so bloody at that time,

Over the moss ten yeomen they see,

Come for to take Sir Hugh in the Grime.

Sir Hugh set his back against a tree,

And then the men encompast him round;

His mickle sword from his hand did flee,

And then they brought Sir Hugh to the ground.

Sir Hugh of the Grime now taken is

And brought back to Garlard town;

[Then cry'd] the good wives all in Garlard town,

'Sir Hugh in the Grime, thou 'st ner gang down.

'

The good Lord Bishop is come to the town,

And on the bench is set so high;

And every man was taxt to his crime,

At length he called Sir Hugh in the Grime.

'Here am I, thou false bishop,

Thy humours all to fulfill;

I do not think my fact so great

But thou mayst put it into thy own will.'

The quest of jury-men was calld,

The best that was in Garlard town;

Eleven of them spoke all in a breast,

'Sir Hugh in the Grime, thou 'st ner gang down.

'

Then another questry-men was calld,

The best that was in Rumary;

Twelve of them spoke all in a breast,

'Sir Hugh in the Grime, thou'st now guilty.'

Then came down my good Lord Boles,

Falling down upon his knee:

'Five hundred peices of gold would I give,

To grant Sir Hugh in the Grime to me.'

'Peace, peace, my good Lord Boles,

And of your speeches set them by!

If there be eleven Grimes all of a name,

Then by my own honour they all should dye.'

Then came down my good Lady Ward,

Falling low upon her knee:

'Five hundred measures of gold I'le give,

To grant Sir Hugh of the Grime to me.'

'Peace, peace, my good Lady Ward,

None of your proffers shall him buy!

For if there be twelve Grimes all of a name,

By my own honour they all should dye.'

Sir Hugh of the Grime's condemnd to dye,

And of his friends he had no lack;

Fourteen foot he leapt in his ward,

His hands bound fast upon his back.

Then he lookt over his left shoulder,

To see whom he could see or spy;

Then was he aware of his father dear,

Came tearing his hair most pittifully.

'Peace, peace, my father dear,

And of your speeches set them by!

Though they have bereavd me of my life,

They cannot bereave me of heaven so high.'

He lookt over his right shoulder,

To see whom he could see or spye;

There was he aware of his mother dear,

Came tearing her hair most pittifully.

'Pray have me remembred to Peggy, my wife;

As she and I walkt over the moor,

She was the cause of [the loss of] my life,

And with the old bishop she plaid the whore.

'Here, Johnny Armstrong, take thou my sword,

That is made of the mettle so fine,

And when thou comst to the border-side,

Remember the death of Sir Hugh of the Grime.

Contributed by Bernart Bartleby - 2018/3/22 - 22:45

Language: Italian

Traduzione italiana di Riccardo Venturi

23 marzo 2018 20:55

23 marzo 2018 20:55

HUGH GRAEME

Così ebbe a accadere una volta

Quando l'annata è verso mezz'estate,

Si accusavano un po' tutti quanti

D'aver rubato la giumenta del buon signor Vescovo.

Il bravo Lord Screw, lui, sellò un cavallo

E cavalcò in cerca di quella stessa lotta; [1]

Prima di arrivare sulla brughiera

Si accorse che c'era Sir Hugh Graeme.

“Vòltati, vòltati, tu, bugiardo e traditore,

Vòltati, e arrenditi a me;

Tu hai rubato la giumenta del signor Vescovo,

E ora pensi di svignartela.”

“Eh no, calma Lord Screw! Non può essere!

Qui c'è una grossa spada al mio fianco,

E sei sei capace di impadronirti di me,

Si vedrà presto chi vincerà.”

“Non ho mai temuto un traditore audace,

Anche se ti chiami Hugh Graeme;

Ti farò pentire dei tuoi stupidi discorsi,

Se solo il giorno e la vita me ne daranno il tempo.”

“E allora fai del tuo peggio, buon Lord Screw,

E distribuisci i tuoi colpi il più veloce che puoi;

Si vedra chi dei due, fra me e te,

Sarà il migliore.”

E quindi, mentre si tiravan colpi a rondemà [2]

E tutt'e due all'ultimo sangue [3] in quel frangente,

Sulla brughiera vedono dieci agrari in armi [4]

Che arrivano per catturare Sir Hugh Graeme.

Sir Hugh si ritrovò con la schiena contro un albero

E allora gli uomini lo circondarono;

La grossa spada gli scivolò dalla mano

E allora Sir Hugh lo misero a terra.

Sir Hugh Graeme ora è catturato

E riportato alla città di Carlisle; [5]

[E allora urlavano] tutte le brave donne di Carlisle,

“Sir Hugh Grame, non sei mai stato sconfitto.”

Il buon signor Vescovo è arrivato in città,

E si è messo lassù in alto su uno scanno;

Tutti quanti eran sottoposti alle accuse,

E dopo un bel po' chiamò Sir Hugh Graeme.

“Eccomi qua, bugiardo d'un vescovo,

Per soddisfare tutte le tue fregole;

Non penso di avere fatto granché di male,

Ma tu puoi rigirarla come ti pare.”

Fu chiesto il parere dei giurati,

I migliori che c'erano a Carlisle;

Undici di loro parlarono all'unisono:

“Sir Hugh Graeme, non sei mai stato sconfitto”.

Allora furono chiamati altri giurati,

Il migliore che c'era sulla Roman Fell [6];

Dodici di loro parlarono all'unisono:

“Sir Hugh Graeme, ora sei colpevole.”

Allora il mio buon Lord Boles,

Si alzò da sedere e si mise in ginocchio:

“Darei cinquecento monete d'oro

Per farmi dare Sir Hugh Graeme.”

“Calmo, calmo, mio buon Lord Boles,

Smettetela con questi discorsi!

Se ci fossero undici Graeme con lo stesso nome,

Allora, sul mio onore, dovrebbero tutti morire.”

E allora la mia buona Lady Ward

Si alzò da sedere e si mise in ginocchio:

“Darei cinquecento misure d'oro

Per farmi dare Sir Hugh Graeme.”

“Calma, calma, mia buona Lady Ward,

Nessuna delle vostre profferte ve lo farà comprare!

Perché, se ci fossero dodici Graeme con lo stesso nome,

Allora, sul mio onore, dovrebbero tutti morire.”

Sir Hugh Graeme è condannato a morte,

E di amici suoi, non gliene mancavano;

Quattordici piedi ballavano come a fargli la guardia, [7]

E lui stava con le mani legate strette dietro la schiena.

Allora lui si guardò dietro alla spalla sinistra

Per vedere chi poteva vedere o scorgere;

Si accorse allora del suo amato padre

Che arrivava strappandosi i capelli da far davvero pena.

“Càlmati, càlmati, mio amato padre,

E lascia da parte ogni discorso!

Anche se mi hanno privato della vita

Non possono privarmi dell'Alto de' Cieli.”

Si guardò dietro alla spalla destra

Per vedere chi poteva vedere o scorgere;

Si accorse allora della sua amata madre

Che arrivava strappandosi i capelli da far davvero pena.

“Ti prego di farmi ricordare da Peggy, mia moglie;

Di quando io e lei passeggiavamo per la brughiera,

E' stato per lei che ho perso la vita,

E con il vecchio vescovo faceva la puttana.

“Vieni qui, Johnny Armstrong [8], prendi tu la mia spada,

Che è fatta di ottima tempra,

E quando vieni dalle parti della Frontiera,

Rammentati della morte di Sir Hugh Graeme.”

Così ebbe a accadere una volta

Quando l'annata è verso mezz'estate,

Si accusavano un po' tutti quanti

D'aver rubato la giumenta del buon signor Vescovo.

Il bravo Lord Screw, lui, sellò un cavallo

E cavalcò in cerca di quella stessa lotta; [1]

Prima di arrivare sulla brughiera

Si accorse che c'era Sir Hugh Graeme.

“Vòltati, vòltati, tu, bugiardo e traditore,

Vòltati, e arrenditi a me;

Tu hai rubato la giumenta del signor Vescovo,

E ora pensi di svignartela.”

“Eh no, calma Lord Screw! Non può essere!

Qui c'è una grossa spada al mio fianco,

E sei sei capace di impadronirti di me,

Si vedrà presto chi vincerà.”

“Non ho mai temuto un traditore audace,

Anche se ti chiami Hugh Graeme;

Ti farò pentire dei tuoi stupidi discorsi,

Se solo il giorno e la vita me ne daranno il tempo.”

“E allora fai del tuo peggio, buon Lord Screw,

E distribuisci i tuoi colpi il più veloce che puoi;

Si vedra chi dei due, fra me e te,

Sarà il migliore.”

E quindi, mentre si tiravan colpi a rondemà [2]

E tutt'e due all'ultimo sangue [3] in quel frangente,

Sulla brughiera vedono dieci agrari in armi [4]

Che arrivano per catturare Sir Hugh Graeme.

Sir Hugh si ritrovò con la schiena contro un albero

E allora gli uomini lo circondarono;

La grossa spada gli scivolò dalla mano

E allora Sir Hugh lo misero a terra.

Sir Hugh Graeme ora è catturato

E riportato alla città di Carlisle; [5]

[E allora urlavano] tutte le brave donne di Carlisle,

“Sir Hugh Grame, non sei mai stato sconfitto.”

Il buon signor Vescovo è arrivato in città,

E si è messo lassù in alto su uno scanno;

Tutti quanti eran sottoposti alle accuse,

E dopo un bel po' chiamò Sir Hugh Graeme.

“Eccomi qua, bugiardo d'un vescovo,

Per soddisfare tutte le tue fregole;

Non penso di avere fatto granché di male,

Ma tu puoi rigirarla come ti pare.”

Fu chiesto il parere dei giurati,

I migliori che c'erano a Carlisle;

Undici di loro parlarono all'unisono:

“Sir Hugh Graeme, non sei mai stato sconfitto”.

Allora furono chiamati altri giurati,

Il migliore che c'era sulla Roman Fell [6];

Dodici di loro parlarono all'unisono:

“Sir Hugh Graeme, ora sei colpevole.”

Allora il mio buon Lord Boles,

Si alzò da sedere e si mise in ginocchio:

“Darei cinquecento monete d'oro

Per farmi dare Sir Hugh Graeme.”

“Calmo, calmo, mio buon Lord Boles,

Smettetela con questi discorsi!

Se ci fossero undici Graeme con lo stesso nome,

Allora, sul mio onore, dovrebbero tutti morire.”

E allora la mia buona Lady Ward

Si alzò da sedere e si mise in ginocchio:

“Darei cinquecento misure d'oro

Per farmi dare Sir Hugh Graeme.”

“Calma, calma, mia buona Lady Ward,

Nessuna delle vostre profferte ve lo farà comprare!

Perché, se ci fossero dodici Graeme con lo stesso nome,

Allora, sul mio onore, dovrebbero tutti morire.”

Sir Hugh Graeme è condannato a morte,

E di amici suoi, non gliene mancavano;

Quattordici piedi ballavano come a fargli la guardia, [7]

E lui stava con le mani legate strette dietro la schiena.

Allora lui si guardò dietro alla spalla sinistra

Per vedere chi poteva vedere o scorgere;

Si accorse allora del suo amato padre

Che arrivava strappandosi i capelli da far davvero pena.

“Càlmati, càlmati, mio amato padre,

E lascia da parte ogni discorso!

Anche se mi hanno privato della vita

Non possono privarmi dell'Alto de' Cieli.”

Si guardò dietro alla spalla destra

Per vedere chi poteva vedere o scorgere;

Si accorse allora della sua amata madre

Che arrivava strappandosi i capelli da far davvero pena.

“Ti prego di farmi ricordare da Peggy, mia moglie;

Di quando io e lei passeggiavamo per la brughiera,

E' stato per lei che ho perso la vita,

E con il vecchio vescovo faceva la puttana.

“Vieni qui, Johnny Armstrong [8], prendi tu la mia spada,

Che è fatta di ottima tempra,

E quando vieni dalle parti della Frontiera,

Rammentati della morte di Sir Hugh Graeme.”

[1] Il testo riportato dal Child presenta qui un misspelling, serime; nei testi è riportato usualmente alla forma scrime, antiquato termine per “lotta, combattimento”. E' quello poi passato in francese come escrime, a indicare lo sport della scherma.

[2] Termine tipicamente livornese, ma è a mio parere l'unico che rende bene quel che si dice nel testo originale. Il termine livornese deriva peraltro dal francese: à ronde main.

[3] All'epoca, il termine bloody aveva ancora il significato proprio di “sanguinoso, cruento”. Quel che significa adesso lo sanno tutti. Si narra di un turista italiano a Londra che aveva chiesto al cameriere di un ristorante ”A bloody steak”, intendendo una “bistecca al sangue”. Il cameriere rispose: ”Would you like some fucking chips with it, too?”

[4] Difficile tradurre bene yeoman (termine derivato storicamente da young man. In genere indica(va) un piccolo proprietario terriero che prestava servizio in fanteria, oppure si armava a difesa degli interessi del grande latifondista appartenente alla grande aristocrazia.

[5] Il testo della versione A di questa ballata è corrotto, inesatto, sgrammaticato, dialettale. Garlard è Carlisle, l'importante e storica città del Cumberland (a soli 16 km di distanza dallo Scottish Border). Il suo nome è di origine brittònica, qualcosa come Car L(e)uel “città di Luel”. Si ricordi che, comunque, la pronuncia standard di “Carlisle” è [kar'la:jl].

[6] Nei pressi di Carlisle sorge la Roman Fell, “Altura Romana”, testimone di un'antichità remota. E' detta localmente Romary, o Rumary.

[7] L'apparente incongruenza del testo (“he leapt” ecc.) è probabilmente dovuta al fatto che il pronome di III plurale, they, di origine scandinava (isl. Þeir) si è generalizzato in inglese in epoca molto tarda, e a livello dialettale non lo è nemmeno adesso. Si potrebbe qui avere un derivato dalla forma autentica anglosassone, hīe “essi, loro”.

[8] Altro outlaw, a sua volta protagonista della sua ballata “in proprio”, Johnie Armstrong (Child #169). Le “Border Ballads” possono in un certo senso essere viste come un corpus epico popolare.

[2] Termine tipicamente livornese, ma è a mio parere l'unico che rende bene quel che si dice nel testo originale. Il termine livornese deriva peraltro dal francese: à ronde main.

[3] All'epoca, il termine bloody aveva ancora il significato proprio di “sanguinoso, cruento”. Quel che significa adesso lo sanno tutti. Si narra di un turista italiano a Londra che aveva chiesto al cameriere di un ristorante ”A bloody steak”, intendendo una “bistecca al sangue”. Il cameriere rispose: ”Would you like some fucking chips with it, too?”

[4] Difficile tradurre bene yeoman (termine derivato storicamente da young man. In genere indica(va) un piccolo proprietario terriero che prestava servizio in fanteria, oppure si armava a difesa degli interessi del grande latifondista appartenente alla grande aristocrazia.

[5] Il testo della versione A di questa ballata è corrotto, inesatto, sgrammaticato, dialettale. Garlard è Carlisle, l'importante e storica città del Cumberland (a soli 16 km di distanza dallo Scottish Border). Il suo nome è di origine brittònica, qualcosa come Car L(e)uel “città di Luel”. Si ricordi che, comunque, la pronuncia standard di “Carlisle” è [kar'la:jl].

[6] Nei pressi di Carlisle sorge la Roman Fell, “Altura Romana”, testimone di un'antichità remota. E' detta localmente Romary, o Rumary.

[7] L'apparente incongruenza del testo (“he leapt” ecc.) è probabilmente dovuta al fatto che il pronome di III plurale, they, di origine scandinava (isl. Þeir) si è generalizzato in inglese in epoca molto tarda, e a livello dialettale non lo è nemmeno adesso. Si potrebbe qui avere un derivato dalla forma autentica anglosassone, hīe “essi, loro”.

[8] Altro outlaw, a sua volta protagonista della sua ballata “in proprio”, Johnie Armstrong (Child #169). Le “Border Ballads” possono in un certo senso essere viste come un corpus epico popolare.

Language: English (Inglese Scozzese)

HUGHIE GRAME (or HUGHIE THE GRAEME)

The Laird o' Hume he's a huntin' gone

Over the hills and mountains clear,

And he has ta'en Sir Hugh the Grame

For stealin' o' the Bishop's mear.

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

They hae ta'en Sir Hugh the Grame

And led him doon through Strievling toon,

Fifteen o' them cried oot at ance,

"Sir Hugh the Grame he must gae doon!"

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

"Were I to die," said Hugh the Grame

"My parents would think it a very great lack"

Full fifteen feet in the air he jumped

Wi' his hands bound fast behind his back.

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

Then oot and spak the Lady Black,

And o' her will she was right free,

"A thousand pounds, my lord, I'll give

If Hugh the Grame set free to me."

"Haud your tongue, ye Lady Black

And ye'll let a' your pleading be!

Though ye would gie me thousands ten

It's for my honour he would die."

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

Then oot it spak her Lady Hume

And aye a sorry woman was she,

"I'll gie ye a hundred milk-white steeds

Gin ye'll gie Sir Hugh the Grame to me."

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

"O Haud your tongue, ye Lady Hume

And ye'll let a' your pleading be!

Though a' the Grames were in this court,

He should be hanged high for me."

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

He lookit ower his left shoulder

It was to see what he could see,

And there he saw his auld faither

Weeping and wailing bitterly.

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

"O, haud your tongue, my auld faither

And ye'll let a' your mournin' be!

For if they bereave me o' my life

They canna haud the heavens frae me."

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

"You'll gie my brother, John, the sword

That's pointed with the metal clear,

And bid him come at eight o'clock

And see me pay the Bishop'e mear."

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

"And brother James, tak' here the sword

That's pointed wi' the metal brown

Come up the morn at eight o'clock

And see your brother putten down."

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

Ye'll tell this news to Maggie, my wife

Neist time ye gang to Strievling toon,

She is the cause I lose my life

She wi' the Bishop played the loon.

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

The Laird o' Hume he's a huntin' gone

Over the hills and mountains clear,

And he has ta'en Sir Hugh the Grame

For stealin' o' the Bishop's mear.

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

They hae ta'en Sir Hugh the Grame

And led him doon through Strievling toon,

Fifteen o' them cried oot at ance,

"Sir Hugh the Grame he must gae doon!"

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

"Were I to die," said Hugh the Grame

"My parents would think it a very great lack"

Full fifteen feet in the air he jumped

Wi' his hands bound fast behind his back.

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

Then oot and spak the Lady Black,

And o' her will she was right free,

"A thousand pounds, my lord, I'll give

If Hugh the Grame set free to me."

"Haud your tongue, ye Lady Black

And ye'll let a' your pleading be!

Though ye would gie me thousands ten

It's for my honour he would die."

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

Then oot it spak her Lady Hume

And aye a sorry woman was she,

"I'll gie ye a hundred milk-white steeds

Gin ye'll gie Sir Hugh the Grame to me."

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

"O Haud your tongue, ye Lady Hume

And ye'll let a' your pleading be!

Though a' the Grames were in this court,

He should be hanged high for me."

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

He lookit ower his left shoulder

It was to see what he could see,

And there he saw his auld faither

Weeping and wailing bitterly.

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

"O, haud your tongue, my auld faither

And ye'll let a' your mournin' be!

For if they bereave me o' my life

They canna haud the heavens frae me."

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

"You'll gie my brother, John, the sword

That's pointed with the metal clear,

And bid him come at eight o'clock

And see me pay the Bishop'e mear."

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

"And brother James, tak' here the sword

That's pointed wi' the metal brown

Come up the morn at eight o'clock

And see your brother putten down."

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

Ye'll tell this news to Maggie, my wife

Neist time ye gang to Strievling toon,

She is the cause I lose my life

She wi' the Bishop played the loon.

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

Contributed by B.B. - 2018/3/23 - 08:22

Language: English

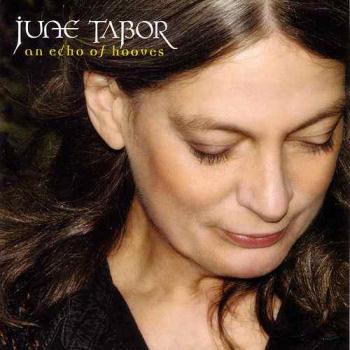

La versione di June Tabor, trovata su Mainly Norfolk: English and Scottish Folk and Other Good Music

HUGHIE GRAEME

Lords are to the mountains gone,

A-hunting of the fallow deer;

They have grippit Hughie Graeme

For stealing of the bishop's mare.

They have bound him hand and foot,

And led him up through Carlisle town;

All the lads along the way

Cried, “Hughie Graeme you shall hang.”

“Loose my right hand free, he says,

Put my broadsword in my hand;

There's none in Carlisle town this day,

Dare tell the tale to Hughie Graeme.”

Up and spake the good Whitefoord,

As he sat by the Bishop's knee,

“Five hundred white stots [young oxen] I'll give you,

If you'll give Hughie Graeme to me.”

“Hold your tongue, my noble lord,

And of your pleading let it be,

Although ten Graemes were in this court,

Hughie Graeme this day shall die.”

Up and spake the fair Whitefoord,

As she sat by the Bishop's knee;

“Five hundred white pence I'll give you,

If you'll let Hughie Graeme go free.”

“Hold your tongue, my lady fair,

And of your weeping let it be;

Although ten Graemes were in this court,

It's for my honour he must die.”

They've ta'en him to the hanging hill

And led him to the gallows tree;

Ne'er the colour left his cheek,

Nor ever did he blink his eye.

Then he's looked him round about,

Al for to see what he could see;

There he saw his father dear,

Weeping, weeping bitterly.

“Hold your tongue, my father dear,

And of your weeping let it be;

It sorer, sorer grieves my heart

Than all that they could do to me.

And you may give my brother John

My sword that's made of the metal clear;

And bid him come at twelve of the clock

And see me pay the Bishop's mare.

And you may give my brother James

My sword that's made of the metal brown;

And bid him come at four of the clock

And see his brother Hugh cut down.

Remember me to Maggy my wife,

The next time ye come o'er the moor;

Tell her, she stole the Bishop's mare,

Tell her, she was the Bishop's whore.

And you may tell my kith and kin,

I never did disgrace their blood;

And when they meet the Bishop's cloak,

Leave it shorter by the hood.”

Lords are to the mountains gone,

A-hunting of the fallow deer;

They have grippit Hughie Graeme

For stealing of the bishop's mare.

They have bound him hand and foot,

And led him up through Carlisle town;

All the lads along the way

Cried, “Hughie Graeme you shall hang.”

“Loose my right hand free, he says,

Put my broadsword in my hand;

There's none in Carlisle town this day,

Dare tell the tale to Hughie Graeme.”

Up and spake the good Whitefoord,

As he sat by the Bishop's knee,

“Five hundred white stots [young oxen] I'll give you,

If you'll give Hughie Graeme to me.”

“Hold your tongue, my noble lord,

And of your pleading let it be,

Although ten Graemes were in this court,

Hughie Graeme this day shall die.”

Up and spake the fair Whitefoord,

As she sat by the Bishop's knee;

“Five hundred white pence I'll give you,

If you'll let Hughie Graeme go free.”

“Hold your tongue, my lady fair,

And of your weeping let it be;

Although ten Graemes were in this court,

It's for my honour he must die.”

They've ta'en him to the hanging hill

And led him to the gallows tree;

Ne'er the colour left his cheek,

Nor ever did he blink his eye.

Then he's looked him round about,

Al for to see what he could see;

There he saw his father dear,

Weeping, weeping bitterly.

“Hold your tongue, my father dear,

And of your weeping let it be;

It sorer, sorer grieves my heart

Than all that they could do to me.

And you may give my brother John

My sword that's made of the metal clear;

And bid him come at twelve of the clock

And see me pay the Bishop's mare.

And you may give my brother James

My sword that's made of the metal brown;

And bid him come at four of the clock

And see his brother Hugh cut down.

Remember me to Maggy my wife,

The next time ye come o'er the moor;

Tell her, she stole the Bishop's mare,

Tell her, she was the Bishop's whore.

And you may tell my kith and kin,

I never did disgrace their blood;

And when they meet the Bishop's cloak,

Leave it shorter by the hood.”

Contributed by B.B. - 2018/3/23 - 08:49

Il buon BB è riuscito a beccare una Child Ballad che non avevo mai tradotto a partire dal 1982 o giù di lì: gliene va dato il dovuto atto e onore. In realtà non avevo mai pensato di occuparmi di questa Border Ballad, lo riconosco: le Border Ballads sono in generale molto belle, ma anche abbastanza ripetitive nel descrivere le vicende di quella terra senza legge tra i secoli XVI e XVII. Terra senza legge, quindi terreno straordinariamente fertile per ogni tipo di ballata epica, esattamente come il Wild West americano, come i Balcani, come l'Italia meridionale ai tempi della "guerra al brigantaggio". Ci sono due considerazioni fondamentali da fare sulle Border Ballads: la prima è che fioriscono in un periodo dove tutti si sbudellavano allegramente con tutti, senza nessuna questione di "torto" o "ragione": era così e basta. La seconda è che la balladry, come sempre, e come in ogni epoca e paese, tendeva a prendere comunque le parti dell'outlaw, a prescindere. Nella balladry, l'autorità costituita, emanazione di un potere visto sempre come lontano e ostile, non è stata mai amata, Robin Hood docet ma docunt anche molti altri "banditi" di ogni luogo (si veda la santificazione maremmana del Tiburzi, che alla fin fine è risultato essere poco più che un guardiano al servizio degli agrari). Insomma, dico che bisogna sempre stare un po' attenti e "situarsi" con attenzione storica. Il "buon bandito" delle leggende romantiche non è mai esistito e bisogna tenerlo bene in mente. Quanto alla ballata in sé, mi sto dedicando alla traduzione con un po' di oliatura alle giunture, sono un po' arrugginito col "Ballad English" e chiedo venia. Ho riportato il titolo alla dizione del Child ("Hughie Grame") e suddiviso il testo in quartine come di solito si fa (e come faceva il Child). Nei testi delle Child Ballads, di solito le quartine sono numerate progressivamente, ma qui non farebbe un bell'effetto grafico a mio parere. La numerazione childiana è stata tolta dal titolo e riportata in testa alle indicazioni autoriali, come è sempre stato fatto in questo sito.

Riccardo Venturi - 2018/3/23 - 19:14

Grazie Riccardo, chissà perchè ma ti avrei visto bene a cavalcare, menar le mani, bere ed amoreggiare sui Borders tra XVI e XVII secolo... Forse avresti avuto l'autorevolezza per mettere un po' ordine anche lassù, così come sei solito fare sulle pagine delle CCG/AWS!

Ciau!

Ciau!

B.B. - 2018/3/23 - 21:19

Ma guarda che queste erano le attività usuali del mio avo, l'Anonimo Scozzese del XVI Secolo! Ivi compreso catalogare e manoscrìvere Border Ballads, quell'ingrato di Francesco Giacomo Infante poteva anche citarlo una piccola volta nella sua raccolta, ma dico io...

Riccardo Venturi - 2018/3/23 - 21:28

La ballata è classificata nel corpus childiano al numero 191 in svariate varianti ma sono solo due le versioni più diffuse nel folk revival: quella di Robert Burns e quella di Walter Scott.

Anche per le melodie non c'è univocità.

Per la pubblicazione nello Scots Musical Museum il bardo di Scozia raccoglie la ballata di Hughie Graeme dalla tradizione orale dell’Ayrshie, rimaneggiando alcune strofe e aggiungendone di sue, così June Tabor e i Malinky seguono la versione testuale di Burns così come i Corries che ci rilasciano una versione più condensata

Ewan MacColl registra due versioni testuali della ballata con due diverse melodie

con Ewan MacColl & Peggy Seeger – Hughie the Graeme in Classic Scots Ballads, 1956 {for tune cf. Bronson’s #4}riprende la melodia trascritta da Gavin Greig dalla testimonianza delle signora Lyall di Skene, vicino ad Aberdeen (Aberdeenshire) e invece in in The English and Scottish Popular Ballads (The Child Ballads), Volume II {Bronson’s #6} segue un motivo imparato da Thomas Armstrong di Newcastle

https://terreceltiche.altervista.org/h...

Anche per le melodie non c'è univocità.

Per la pubblicazione nello Scots Musical Museum il bardo di Scozia raccoglie la ballata di Hughie Graeme dalla tradizione orale dell’Ayrshie, rimaneggiando alcune strofe e aggiungendone di sue, così June Tabor e i Malinky seguono la versione testuale di Burns così come i Corries che ci rilasciano una versione più condensata

Ewan MacColl registra due versioni testuali della ballata con due diverse melodie

con Ewan MacColl & Peggy Seeger – Hughie the Graeme in Classic Scots Ballads, 1956 {for tune cf. Bronson’s #4}riprende la melodia trascritta da Gavin Greig dalla testimonianza delle signora Lyall di Skene, vicino ad Aberdeen (Aberdeenshire) e invece in in The English and Scottish Popular Ballads (The Child Ballads), Volume II {Bronson’s #6} segue un motivo imparato da Thomas Armstrong di Newcastle

https://terreceltiche.altervista.org/h...

Cattia Salto - 2019/2/26 - 17:49

Language: Italian

HUGHIE GRAEME Child #191 B (June Tabor)

I nostri Lord sono andati sulle montagne

A cacciare il daino

Hanno arrestato Hughie Graeme,

Per aver rubato la giumenta del vescovo.

Lo hanno legato mani e piedi

E riportato alla città di Carlisle (1);

I ragazzi (e le ragazze) lungo il cammino,

Urlavano, ‘Hughie Graeme, sarai impiccato’!

“Liberate la mia mano destra-dice lui-

e mettetemi lo spadone in mano;

Non c’è nessuno a Carlisle questo giorno

Che oserà raccontare favole a (2) Hughie Graeme.”

Si alzò a parlare il buon Lord Whitefoord,

E s’inginocchiò davanti al vescovo:

“Darei cinquecento giovani buoi

Se voi mi darete Sir Hugh Graeme.”

V

“Frenate la lingua, mio buon Lord

Smettetela con questa supplica!

Anche se ci fossero dieci Graeme in questa corte,

Hugh Graeme morirà oggi.”

Si alzò a parlare la bella Whitefoord

E s’inginocchiò davanti al vescovo:

“Darei cinquecento misure d’argento

Se farete liberare Hugh Graeme.”

“Frenate la lingua, mia bella Lady

E smettetela con la lagna!

Anche se ci fossero dodici Graeme in questa corte,

E’ per il mio onore, che deve morire”

Lo hanno portato alla collina della forca

E messo sotto la forca

Mai il colore lasciò le sue guance

E nemmeno strizzò gli occhi

Allora lui si guardò dietro alla spalla sinistra

Per vedere cosa riusciva scorgere;

Si accorse allora del suo amato padre

Che piangeva, piangeva amaramente

“Taci, mio amato padre,

E smettila di piangere!

Ciò mi addolora assai più (3)

Di tutto quello che potrebbero farmi

E tu darai a mio fratello John

la mia spada che è fatta d’acciaio

e pregalo di venire alle 12 in punto

Per vedermi pagare la giumenta del Vescovo

E tu darai a mio fratello James

la mia spada che è fatta d’acciaio brunito

e pregalo di venire alle 4 in punto

Per vedere suo fratello Hugh penzolare”

“Ricordami a Maggy mia moglie;

La prossima volta che passerai per la brughiera,

Dille che lei rubò la giumenta del Vescovo (4),

dille che era lei la puttana del Vescovo.

E dirai ai miei cari

Che non ho mai disonorato il loro lignaggio

E quando incontreranno il mantello del Vescovo

Che lo accorcino dal cappuccio (5)”

A cacciare il daino

Hanno arrestato Hughie Graeme,

Per aver rubato la giumenta del vescovo.

Lo hanno legato mani e piedi

E riportato alla città di Carlisle (1);

I ragazzi (e le ragazze) lungo il cammino,

Urlavano, ‘Hughie Graeme, sarai impiccato’!

“Liberate la mia mano destra-dice lui-

e mettetemi lo spadone in mano;

Non c’è nessuno a Carlisle questo giorno

Che oserà raccontare favole a (2) Hughie Graeme.”

Si alzò a parlare il buon Lord Whitefoord,

E s’inginocchiò davanti al vescovo:

“Darei cinquecento giovani buoi

Se voi mi darete Sir Hugh Graeme.”

V

“Frenate la lingua, mio buon Lord

Smettetela con questa supplica!

Anche se ci fossero dieci Graeme in questa corte,

Hugh Graeme morirà oggi.”

Si alzò a parlare la bella Whitefoord

E s’inginocchiò davanti al vescovo:

“Darei cinquecento misure d’argento

Se farete liberare Hugh Graeme.”

“Frenate la lingua, mia bella Lady

E smettetela con la lagna!

Anche se ci fossero dodici Graeme in questa corte,

E’ per il mio onore, che deve morire”

Lo hanno portato alla collina della forca

E messo sotto la forca

Mai il colore lasciò le sue guance

E nemmeno strizzò gli occhi

Allora lui si guardò dietro alla spalla sinistra

Per vedere cosa riusciva scorgere;

Si accorse allora del suo amato padre

Che piangeva, piangeva amaramente

“Taci, mio amato padre,

E smettila di piangere!

Ciò mi addolora assai più (3)

Di tutto quello che potrebbero farmi

E tu darai a mio fratello John

la mia spada che è fatta d’acciaio

e pregalo di venire alle 12 in punto

Per vedermi pagare la giumenta del Vescovo

E tu darai a mio fratello James

la mia spada che è fatta d’acciaio brunito

e pregalo di venire alle 4 in punto

Per vedere suo fratello Hugh penzolare”

“Ricordami a Maggy mia moglie;

La prossima volta che passerai per la brughiera,

Dille che lei rubò la giumenta del Vescovo (4),

dille che era lei la puttana del Vescovo.

E dirai ai miei cari

Che non ho mai disonorato il loro lignaggio

E quando incontreranno il mantello del Vescovo

Che lo accorcino dal cappuccio (5)”

(1) Robert Burns colloca il processo più a nord, a Stirling (‘Strievelin toun’ )

(2) credo che l’espressione equivalga al nostro “fare la festa” nel senso di uccidere

(3) vedere il padre in lacrime è per Ugo più doloroso della prospettiva di finire impiccato

(4) pesante insulto nei confronti del vescovo che in altre versioni non era così esplicito

(5)che gli taglino la testa!

(2) credo che l’espressione equivalga al nostro “fare la festa” nel senso di uccidere

(3) vedere il padre in lacrime è per Ugo più doloroso della prospettiva di finire impiccato

(4) pesante insulto nei confronti del vescovo che in altre versioni non era così esplicito

(5)che gli taglino la testa!

Contributed by Cattia Salto - 2019/2/26 - 17:59

Language: Italian

HUGHIE GRAME (or HUGHIE THE GRAEME)(versione Ewan MacColl & Peggy Seeger – Hughie the Graeme in Classic Scots Ballads, 1956)

Ewan MacColl riprende la melodia trascritta da Gavin Greig dalla testimonianza delle signora Lyall di Skene, vicino ad Aberdeen (Aberdeenshire).

Il testo è molto simile a Child #191 E (mancante però di ritornello)

Ewan MacColl riprende la melodia trascritta da Gavin Greig dalla testimonianza delle signora Lyall di Skene, vicino ad Aberdeen (Aberdeenshire).

Il testo è molto simile a Child #191 E (mancante però di ritornello)

Il Laird di Hume è andato a caccia

sulle colline e le montagne

E ha sorpreso Sir Hughie Graeme,

A rubare la giumenta del vescovo.

coro

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

Lo hanno legato mani e piedi

E condotto per la città di Stirling;

Una quindicina (1) di loro urlava con una sola voce:

‘Sir Hughie Graeme, sarà impiccato’!

“Se dovessi morire- disse Hughie Graeme,-

I miei genitori la considereranno una grande perdita”

E fece un balzo di 15 piedi in aria

Con le mani legate strette dietro la schiena.

Si alzò a parlare Lady Black,

E di sua spontanea volontà:

“Darei mille sterline mio signore

Se mi libererete Hugh Graeme.”

“Frenate la lingua, voi Lady Black

Smettetela con questa supplica!

Anche se me ne dareste diecimila,

E’ per il mio onore, che deve morire”

Poi si alzò a parlare Lady Hume

E si una donna affranta lei era:

“Vi darei un centinaio di bianchi destrieri

Se mi darete Sir Hugh Graeme.”

“Frenate la lingua, voi Lady Hume

Smettetela con questa supplica!

Anche tutti i Graeme fossero in questa corte,

Dovrebbe essere impiccato in alto per me”

Lui si guardò dietro alla spalla sinistra

Per vedere cosa riusciva scorgere;

Si accorse allora del suo vecchio padre

Che piangeva e piagnucolava amaramente

“Taci, mio amato padre,

E smettila di piangere!

Perchè mi possono portare via la vita

Ma non possono bandirmi dal Paradiso”

Darai a mio fratello John la spada

Che è fatta d’acciaio

e pregalo di venire alle 8 in punto

Per vedermi pagare la giumenta del Vescovo”

“E fratello James prendi la spada

Che è fatta d’acciaio brunito

Ritorna al mattino alle 8 in punto

Per vedere suo fratello penzolare

X

“Darai la notizia a Maggie, mia moglie;

La prossima volta che passerai per Stirling,

Per colpa sua ho perso la vita,

Lei con il Vescovo saltava la cavallina”(1)

sulle colline e le montagne

E ha sorpreso Sir Hughie Graeme,

A rubare la giumenta del vescovo.

coro

Tay ammarey, O Londonderry

Tay ammarey, O London dee.

Lo hanno legato mani e piedi

E condotto per la città di Stirling;

Una quindicina (1) di loro urlava con una sola voce:

‘Sir Hughie Graeme, sarà impiccato’!

“Se dovessi morire- disse Hughie Graeme,-

I miei genitori la considereranno una grande perdita”

E fece un balzo di 15 piedi in aria

Con le mani legate strette dietro la schiena.

Si alzò a parlare Lady Black,

E di sua spontanea volontà:

“Darei mille sterline mio signore

Se mi libererete Hugh Graeme.”

“Frenate la lingua, voi Lady Black

Smettetela con questa supplica!

Anche se me ne dareste diecimila,

E’ per il mio onore, che deve morire”

Poi si alzò a parlare Lady Hume

E si una donna affranta lei era:

“Vi darei un centinaio di bianchi destrieri

Se mi darete Sir Hugh Graeme.”

“Frenate la lingua, voi Lady Hume

Smettetela con questa supplica!

Anche tutti i Graeme fossero in questa corte,

Dovrebbe essere impiccato in alto per me”

Lui si guardò dietro alla spalla sinistra

Per vedere cosa riusciva scorgere;

Si accorse allora del suo vecchio padre

Che piangeva e piagnucolava amaramente

“Taci, mio amato padre,

E smettila di piangere!

Perchè mi possono portare via la vita

Ma non possono bandirmi dal Paradiso”

Darai a mio fratello John la spada

Che è fatta d’acciaio

e pregalo di venire alle 8 in punto

Per vedermi pagare la giumenta del Vescovo”

“E fratello James prendi la spada

Che è fatta d’acciaio brunito

Ritorna al mattino alle 8 in punto

Per vedere suo fratello penzolare

X

“Darai la notizia a Maggie, mia moglie;

La prossima volta che passerai per Stirling,

Per colpa sua ho perso la vita,

Lei con il Vescovo saltava la cavallina”(1)

(1) sono i giurati ovviamente per niente imparziali

(2) to play the loun= to behave unchastely, commit fornication

(2) to play the loun= to behave unchastely, commit fornication

Contributed by Cattia Salto - 2019/2/26 - 18:06

×

![]()

Note for non-Italian users: Sorry, though the interface of this website is translated into English, most commentaries and biographies are in Italian and/or in other languages like French, German, Spanish, Russian etc.

[XVI° secolo?]

Una ballata tradizionale di origine scozzese che Francis James Child riporta in sei o sette versioni (quella che propongo è la prima) nella sua raccolta “The English and Scottish Popular Ballads” (1882-1898), ma che si trova già nel “Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border” di Sir Walter Scott (1802-1803)

Ripresa da Ewan MacColl, senza e con Peggy Seeger, negli anni 50, per esempio in “The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Volume III” del 1956 e “Classic Scots Ballads” del 1959.

Interpretata poi da molti altri artisti, una su tutti June Tabor

Sir Walter Scott descriveva così le "Border Ballads" di cui "Hughie Graham" è una delle più famose:

Metti pure che Hughie Graham (o Graeme) fosse uno dei sanguinari capi clan delle "Scottish Marches" o, più semplicemente, uno dei tagliagole che nel XVI° e XVII° secolo scorrazzavano a nord del Tyne, nella zona delle Cheviot Hills, tra il Northumberland ed il confine meridionale della Scozia... E metti pure che davvero avesse rubato una cavalla, o ucciso un cervo, appartenente al vescovo di Carlisle... E metti anche che per sfuggire agli scherani del vescovo ne avesse passato qualcuno a fil di spada, prima di essere sopraffatto e catturato... Ma Hughie Graham aveva compiuto il suo crimine solo per odio e vendetta contro il laido e turpe vescovo, che gli aveva circuito la moglie (quella baldracca!), ed era stato condannato all'impiccagione solo grazie ad una giuria prezzolata dal suo stesso potente carnefice, che non vedeva l'ora di liberarsi di lui.

E Hughie Graham andrà con fierezza incontro alla morte, ma non prima di aver passato il testimone, la sua spada, a Johnny Armstrong, un altro esponente dei clan dei borders...