My brown skin baby, they take him away

As a young preacher I used to ride a quiet pony ’round the countryside

In a native camp I’ll never forget, a young black mother, her cheeks all wet.

My brown skin baby, they take him away

Between her sobs I heard her say, Police been taking my baby away,

From white man was that baby I had. Why he let them take baby away?

My brown skin baby, they take him away

To a children’s home a baby came with new clothes on and a new name

Day and night he would always say, Oh mommy, mommy, why they take me away?

The child grew up and had to go from the mission home that he loved so

To find his mother, he tried in vain. Upon this earth they never met again.

My brown skin baby, they take him away

As a young preacher I used to ride a quiet pony ’round the countryside

In a native camp I’ll never forget, a young black mother, her cheeks all wet.

My brown skin baby, they take him away

Between her sobs I heard her say, Police been taking my baby away,

From white man was that baby I had. Why he let them take baby away?

My brown skin baby, they take him away

To a children’s home a baby came with new clothes on and a new name

Day and night he would always say, Oh mommy, mommy, why they take me away?

The child grew up and had to go from the mission home that he loved so

To find his mother, he tried in vain. Upon this earth they never met again.

My brown skin baby, they take him away

Contributed by Dq82 - 2017/10/8 - 17:09

×

![]()

Note for non-Italian users: Sorry, though the interface of this website is translated into English, most commentaries and biographies are in Italian and/or in other languages like French, German, Spanish, Russian etc.

QUesta canzone scritta da Bob Randall racconta la sua esperienza di bambino rubato, come avveniva per i figli degli aborigeni in nome dell'assimilazione culturale.

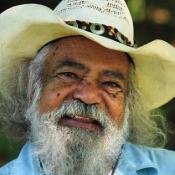

The song is autobiographical. It begins by discussing Randall’s early life. As a boy, he spent the first years of his life on a farm in the Northern Territory with his family, riding a pony. Aware that he was at risk of being taken, the women in the family would apply mud to his fair skin everyday to darken the pigment (Randall, 2012). However, when he was seven, a policeman and two trackers arrived on the farm, investigating the murder of livestock. The boy was spotted swimming in the river, revealing his fair skin. The men grabbed him, placed him on a camel and took him to an institution in Alice Springs and gave him the name “Bob Randall”. He was forced to wear clothing and sleep on a bed (that reeked of urine), two activities which were completely foreign to him. Randall remained in the government’s care until he turned 20, after which he was banished for questioning the white authorities.

The song concludes as Randall identifies that he was never able to find his family – “upon this earth they never met again”. This is consistent with most stories. Throughout the assimilation policy, no records were kept of the Aboriginal nation, family name, or identity of the Aboriginal children who were stolen. In contrast to many traumatic stories from the Stolen Generations, Randall spent the rest of his life promoting and preserving Indigenous cultures and histories. He became a Yankunytjatjara Elder and a traditional owner of Uluru.

Randall’s choice of title “Brown Skin Baby” is very important in allowing him to reconcile with his own identity. Indigenous Australians have a history of racial oppression since the European colonization. As noted by Brady and Carey (2000), “for numerous Indigenous Australians, there was a sense of unbelonging”. They were “not white enough to be white” and not “black enough to be black either”. During the twentieth century, these Australians were referred to as “half-castes”. But Randall rejected this term and the repressive dualism. Instead, as suggested by Barney and Macklinary (2010), Randall chose his own term, singing about his own “brown” skin.

coloradomusic.org