Barely a twelvemonth after

The seven days war that put the world to sleep,

Late in the evening the strange horses came.

By then we had made our covenant with silence,

But in the first few days it was so still

We listened to our breathing and were afraid.

On the second day

The radios failed; we turned the knobs; no answer.

On the third day a warship passed us, heading north,

Dead bodies piled on the deck. On the sixth day

A plane plunged over us into the sea. Thereafter

Nothing. The radios dumb;

And still they stand in corners of our kitchens,

And stand, perhaps, turned on, in a million rooms

All over the world. But now if they should speak,

If on a sudden they should speak again,

If on the stroke of noon a voice should speak,

We would not listen, we would not let it bring

That old bad world that swallowed its children quick

At one great gulp. We would not have it again.

Sometimes we think of the nations lying asleep,

Curled blindly in impenetrable sorrow,

And then the thought confounds us with its strangeness.

The tractors lie about our fields; at evening

They look like dank sea-monsters couched and waiting.

We leave them where they are and let them rust:

'They'll molder away and be like other loam.'

We make our oxen drag our rusty plows,

Long laid aside. We have gone back

Far past our fathers' land.

And then, that evening

Late in the summer the strange horses came.

We heard a distant tapping on the road,

A deepening drumming; it stopped, went on again

And at the corner changed to hollow thunder.

We saw the heads

Like a wild wave charging and were afraid.

We had sold our horses in our fathers' time

To buy new tractors. Now they were strange to us

As fabulous steeds set on an ancient shield.

Or illustrations in a book of knights.

We did not dare go near them. Yet they waited,

Stubborn and shy, as if they had been sent

By an old command to find our whereabouts

And that long-lost archaic companionship.

In the first moment we had never a thought

That they were creatures to be owned and used.

Among them were some half a dozen colts

Dropped in some wilderness of the broken world,

Yet new as if they had come from their own Eden.

Since then they have pulled our plows and borne our loads

But that free servitude still can pierce our hearts.

Our life is changed; their coming our beginning.

The seven days war that put the world to sleep,

Late in the evening the strange horses came.

By then we had made our covenant with silence,

But in the first few days it was so still

We listened to our breathing and were afraid.

On the second day

The radios failed; we turned the knobs; no answer.

On the third day a warship passed us, heading north,

Dead bodies piled on the deck. On the sixth day

A plane plunged over us into the sea. Thereafter

Nothing. The radios dumb;

And still they stand in corners of our kitchens,

And stand, perhaps, turned on, in a million rooms

All over the world. But now if they should speak,

If on a sudden they should speak again,

If on the stroke of noon a voice should speak,

We would not listen, we would not let it bring

That old bad world that swallowed its children quick

At one great gulp. We would not have it again.

Sometimes we think of the nations lying asleep,

Curled blindly in impenetrable sorrow,

And then the thought confounds us with its strangeness.

The tractors lie about our fields; at evening

They look like dank sea-monsters couched and waiting.

We leave them where they are and let them rust:

'They'll molder away and be like other loam.'

We make our oxen drag our rusty plows,

Long laid aside. We have gone back

Far past our fathers' land.

And then, that evening

Late in the summer the strange horses came.

We heard a distant tapping on the road,

A deepening drumming; it stopped, went on again

And at the corner changed to hollow thunder.

We saw the heads

Like a wild wave charging and were afraid.

We had sold our horses in our fathers' time

To buy new tractors. Now they were strange to us

As fabulous steeds set on an ancient shield.

Or illustrations in a book of knights.

We did not dare go near them. Yet they waited,

Stubborn and shy, as if they had been sent

By an old command to find our whereabouts

And that long-lost archaic companionship.

In the first moment we had never a thought

That they were creatures to be owned and used.

Among them were some half a dozen colts

Dropped in some wilderness of the broken world,

Yet new as if they had come from their own Eden.

Since then they have pulled our plows and borne our loads

But that free servitude still can pierce our hearts.

Our life is changed; their coming our beginning.

Contributed by Bernart Bartleby - 2017/7/6 - 14:01

Language: Italian

Traduzione italiana di Anna Maria Robustelli da El Ghibli – Rivista online di letteratura della migrazione

I CAVALLI

Appena dodici mesi dopo

la guerra dei sette giorni che mise a dormire il mondo,

di sera tardi arrivarono gli strani cavalli.

Ormai avevamo fatto un patto con il silenzio,

ma i primi giorni era tutto così immobile

che ascoltavamo il respiro e avevamo paura.

Il secondo giorno

le radio vennero meno; girammo le manopole; nulla.

Il terzo giorno una nave da guerra ci oltrepassò, diretta a nord,

corpi morti ammucchiati sul ponte. Il sesto giorno

un aereo si tuffò nel mare. Dopo

nulla. Le radio mute;

e rimangono ancora negli angoli delle cucine,

e stanno, forse, accese, in un milione di stanze

in tutto il mondo. Ma ora pure se parlassero,

se all'improvviso riparlassero,

se a mezzogiorno in punto una voce parlasse,

non ascolteremmo, non le lasceremmo riportare

quel vecchio mondo malvagio che ha inghiottito rapido i suoi figli

in un sol boccone. Noi non lo rivorremmo.

A volte pensiamo alle nazioni addormentate,

avvolte nel loro cieco impenetrabile dolore,

e allora il pensiero ci confonde per quanto è strano.

I trattori sono sparsi per i campi; di sera

sembrano viscidi mostri marini accucciati in attesa.

Li lasciamo arrugginire dove sono:

"Si sgretoleranno e diventeranno altra polvere".

Ai buoi facciamo tirare gli aratri arrugginiti,

da tanto in disuso: siamo arretrati

ben oltre la terra dei nostri padri.

E poi, quella sera

di tarda estate arrivarono gli strani cavalli.

Udimmo un lontano scalpitio sulla strada,

un tambureggiare che si incupiva; si interruppe, riprese

e all'angolo si trasformò in un tuono profondo.

Vedemmo le teste

caricare come un'onda selvaggia e avemmo paura.

Avevamo venduto i cavalli al tempo dei nostri padri

per comprare trattori nuovi. Ora ci sembravano strani

come favolosi destrieri istoriati su uno scudo antico

o illustrazioni in un libro di cavalieri.

Non osavamo avvicinarci. Eppure essi aspettavano,

ostinati e timidi, come se fossero stati mandati

da un antico comando a cercare noi

e quell'arcaica amicizia da tempo perduta.

All'inizio non avevamo pensato

che fossero creature da possedere e usare.

Tra di loro c'erano una mezza dozzina di puledri

venuti alla luce in un punto selvaggio del mondo distrutto,

eppure nuovi come se fossero venuti dal loro Eden.

Da allora tirano i nostri aratri e portano i nostri pesi,

ma quella schiavitù libera penetra ancora i nostri cuori.

La nostra vita è cambiata; la loro venuta ha segnato il nostro inizio.

Appena dodici mesi dopo

la guerra dei sette giorni che mise a dormire il mondo,

di sera tardi arrivarono gli strani cavalli.

Ormai avevamo fatto un patto con il silenzio,

ma i primi giorni era tutto così immobile

che ascoltavamo il respiro e avevamo paura.

Il secondo giorno

le radio vennero meno; girammo le manopole; nulla.

Il terzo giorno una nave da guerra ci oltrepassò, diretta a nord,

corpi morti ammucchiati sul ponte. Il sesto giorno

un aereo si tuffò nel mare. Dopo

nulla. Le radio mute;

e rimangono ancora negli angoli delle cucine,

e stanno, forse, accese, in un milione di stanze

in tutto il mondo. Ma ora pure se parlassero,

se all'improvviso riparlassero,

se a mezzogiorno in punto una voce parlasse,

non ascolteremmo, non le lasceremmo riportare

quel vecchio mondo malvagio che ha inghiottito rapido i suoi figli

in un sol boccone. Noi non lo rivorremmo.

A volte pensiamo alle nazioni addormentate,

avvolte nel loro cieco impenetrabile dolore,

e allora il pensiero ci confonde per quanto è strano.

I trattori sono sparsi per i campi; di sera

sembrano viscidi mostri marini accucciati in attesa.

Li lasciamo arrugginire dove sono:

"Si sgretoleranno e diventeranno altra polvere".

Ai buoi facciamo tirare gli aratri arrugginiti,

da tanto in disuso: siamo arretrati

ben oltre la terra dei nostri padri.

E poi, quella sera

di tarda estate arrivarono gli strani cavalli.

Udimmo un lontano scalpitio sulla strada,

un tambureggiare che si incupiva; si interruppe, riprese

e all'angolo si trasformò in un tuono profondo.

Vedemmo le teste

caricare come un'onda selvaggia e avemmo paura.

Avevamo venduto i cavalli al tempo dei nostri padri

per comprare trattori nuovi. Ora ci sembravano strani

come favolosi destrieri istoriati su uno scudo antico

o illustrazioni in un libro di cavalieri.

Non osavamo avvicinarci. Eppure essi aspettavano,

ostinati e timidi, come se fossero stati mandati

da un antico comando a cercare noi

e quell'arcaica amicizia da tempo perduta.

All'inizio non avevamo pensato

che fossero creature da possedere e usare.

Tra di loro c'erano una mezza dozzina di puledri

venuti alla luce in un punto selvaggio del mondo distrutto,

eppure nuovi come se fossero venuti dal loro Eden.

Da allora tirano i nostri aratri e portano i nostri pesi,

ma quella schiavitù libera penetra ancora i nostri cuori.

La nostra vita è cambiata; la loro venuta ha segnato il nostro inizio.

Contributed by Bernart Bartleby - 2017/7/6 - 14:04

×

![]()

Note for non-Italian users: Sorry, though the interface of this website is translated into English, most commentaries and biographies are in Italian and/or in other languages like French, German, Spanish, Russian etc.

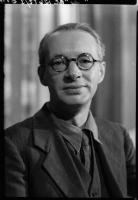

Versi del poeta scozzese Edwin Muir (1887-1959), nell'ultima sua raccolta pubblicata in vita, intitolata “One Foot in Eden”

Musica del songwriter scozzese James Grant, nel suo album del 2002 intitolato “I Shot the Albatross”

Bellissima poesia che celebra il ritorno alla vita dell'uomo, degli animali, del mondo dopo un olocausto nucleare. Un nuovo patto per un nuovo inizio?