A while ago, I got a call from the Tesla Institute in Belgrade, long distance. The voice was very faint and it said, “Understand do we that much of your work has been dedicated to Nikola Tesla and do we know the blackout of information about this man in the U.S. of A. And so we would like to invite you to the Institute as a free citizen of the world ... as a free speaker on American Imperialist Blackout of Information .. Capitalist resistance to Technological Progress ... the Western World’s obstruction of Innovation. So think about it.” He hung up. I thought: Gee, really a chance to speak my mind, and I started doing some research on Tesla, whose life story is actually really sad.

Basically, he was the inventor of AC current, lots of kinds of generators and the Tesla coil. His dream was wireless energy. And he was working on a system in which you could plug appliances directly into the ground. A system which he never really perfected.

Tesla came over from Graz and went to work for Thomas Edison. Edison couldn’t stand Tesla for several reasons. One was that Tesla showed up for work every day in formal dress--morning coat, spats, top hat and gloves--and this just wasn’t the American Way at the time. Edison also hated Tesla because Tesla invented so many things while wearing these clothes.

Edison did his best to prevent conversion to AC and did everything he could to discredit it. In his later years, Edison was something of a showman and he went around on the Chautauqua circuit in upstate New York giving demonstrations of the evil effects of AC. He always brought a dog with him and he’d get up on stage and say: “Ladies and gentlemen! I will now demonstrate the effects of AC current on this dog!” And he took two bare wires and attached them to the dog’s head and the dog was dead in under thirty seconds.

At any rate, I decided to open the series of talks in Belgrade with a song called “The Dance of Electricity” and its beat is derived from an actual dance - an involuntary dance - and it’s the dance you do when one of your fingers gets wedged in a live socket and your arms start pumping up and down and your mouth is slowly opening and closing and you can feel the power but no words will come out.

Basically, he was the inventor of AC current, lots of kinds of generators and the Tesla coil. His dream was wireless energy. And he was working on a system in which you could plug appliances directly into the ground. A system which he never really perfected.

Tesla came over from Graz and went to work for Thomas Edison. Edison couldn’t stand Tesla for several reasons. One was that Tesla showed up for work every day in formal dress--morning coat, spats, top hat and gloves--and this just wasn’t the American Way at the time. Edison also hated Tesla because Tesla invented so many things while wearing these clothes.

Edison did his best to prevent conversion to AC and did everything he could to discredit it. In his later years, Edison was something of a showman and he went around on the Chautauqua circuit in upstate New York giving demonstrations of the evil effects of AC. He always brought a dog with him and he’d get up on stage and say: “Ladies and gentlemen! I will now demonstrate the effects of AC current on this dog!” And he took two bare wires and attached them to the dog’s head and the dog was dead in under thirty seconds.

At any rate, I decided to open the series of talks in Belgrade with a song called “The Dance of Electricity” and its beat is derived from an actual dance - an involuntary dance - and it’s the dance you do when one of your fingers gets wedged in a live socket and your arms start pumping up and down and your mouth is slowly opening and closing and you can feel the power but no words will come out.

Contributed by Bernart Bartleby - 2014/9/15 - 15:55

Language: Italian

Traduzione italiana di Riccardo Venturi

15 settembre 2014

15 settembre 2014

Trg Nikole Tesle (Piazza Nikola Tesla) in un villaggio serbo.

DANZA DELL’ELETTRICITA’ (PER NIKOLA TESLA)

Qualche tempo fa, ricevetti una telefonata dall’Istituto Tesla di Belgrado, molto lontano da qui. La voce si sentiva malissimo e diceva: “Sappiamo che molta della sua opera è stata dedicata a Nikola Tesla, e conosciamo il blackout informativo su quest’uomo negli Stati Uniti. Quindi vorremmo invitarla all’Istituto come libera cittadina del mondo, per parlare liberamente sul blackout informativo imperialista americano…dell’opposizione capitalista al progresso tecnologico…e agli impedimenti frapposti dal mondo occidentale all’innovazione. Ci pensi.” Poi attaccò. Io pensai: Ehi, questa è davvero una chance per dire quello che penso, e cominciai a fare delle ricerche su Tesla, la cui storia di vita è davvero triste.

In pratica fu l’inventore della corrente alternata, di moltissimi tipi di generatore e della bobina di Tesla. Sognava l’energia senza cavi e lavorava a un sistema dove si potessero collegare gli apparecchi direttamente a terra. Un sistema che non realizzò mai.

Tesla era arrivato da Graz e era andati a lavorare per Thomas Edison. Edison non sopportava Tesla per parecchi motivi; uno di questi era che Tesla si presentava ogni giorno al lavoro vestito di tutto punto, giacca da mattina, ghette, cappello a cilindro e guanti; e in America non si faceva così, a quell’epoca. Edison odiava Tesla anche perché inventava un sacco di cose, vestito a quella maniera.

Edison fece tutto quel che poté per impedire il passaggio alla corrente alternata, e la screditava in ogni modo possibile. Edison era una specie di showman, andava allo Chautaqua nel New York settentrionale a fare dimostrazioni degli effetti negativi della corrente alternata. Portava sempre un cane con sé, saliva sul palco e diceva: “Signore e signori! Vi dimostrerò adesso gli effetti della corrente alternata su questo cane!”; quindi prendeva due fili scoperti, li attaccava alla testa del cane e il cane era morto dopo trenta secondi.

In ogni caso, decisi di aprire il ciclo di discorsi a Belgrado con una canzone intitolata “La danza dell’elettricità”; il suo ritmo deriva da una danza autentica, una danza involontaria: quella che si fa quando le dita rimangono attaccate a una presa elettrica, le braccia cominciano a muoversi su e giù e la bocca si apre e si chiude lentamente. Si può sentire l’elettricità, ma non esce nessuna parola.

Qualche tempo fa, ricevetti una telefonata dall’Istituto Tesla di Belgrado, molto lontano da qui. La voce si sentiva malissimo e diceva: “Sappiamo che molta della sua opera è stata dedicata a Nikola Tesla, e conosciamo il blackout informativo su quest’uomo negli Stati Uniti. Quindi vorremmo invitarla all’Istituto come libera cittadina del mondo, per parlare liberamente sul blackout informativo imperialista americano…dell’opposizione capitalista al progresso tecnologico…e agli impedimenti frapposti dal mondo occidentale all’innovazione. Ci pensi.” Poi attaccò. Io pensai: Ehi, questa è davvero una chance per dire quello che penso, e cominciai a fare delle ricerche su Tesla, la cui storia di vita è davvero triste.

In pratica fu l’inventore della corrente alternata, di moltissimi tipi di generatore e della bobina di Tesla. Sognava l’energia senza cavi e lavorava a un sistema dove si potessero collegare gli apparecchi direttamente a terra. Un sistema che non realizzò mai.

Tesla era arrivato da Graz e era andati a lavorare per Thomas Edison. Edison non sopportava Tesla per parecchi motivi; uno di questi era che Tesla si presentava ogni giorno al lavoro vestito di tutto punto, giacca da mattina, ghette, cappello a cilindro e guanti; e in America non si faceva così, a quell’epoca. Edison odiava Tesla anche perché inventava un sacco di cose, vestito a quella maniera.

Edison fece tutto quel che poté per impedire il passaggio alla corrente alternata, e la screditava in ogni modo possibile. Edison era una specie di showman, andava allo Chautaqua nel New York settentrionale a fare dimostrazioni degli effetti negativi della corrente alternata. Portava sempre un cane con sé, saliva sul palco e diceva: “Signore e signori! Vi dimostrerò adesso gli effetti della corrente alternata su questo cane!”; quindi prendeva due fili scoperti, li attaccava alla testa del cane e il cane era morto dopo trenta secondi.

In ogni caso, decisi di aprire il ciclo di discorsi a Belgrado con una canzone intitolata “La danza dell’elettricità”; il suo ritmo deriva da una danza autentica, una danza involontaria: quella che si fa quando le dita rimangono attaccate a una presa elettrica, le braccia cominciano a muoversi su e giù e la bocca si apre e si chiude lentamente. Si può sentire l’elettricità, ma non esce nessuna parola.

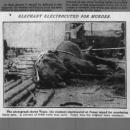

On this date in 1888, a 76-pound Newfoundland was electrocuted before a crowd in a lecture hall at the Columbia College School of Mines (now the School of Engineering and Applied Science at Columbia University) in New York City. The pooch was an innocent bystander who’d fallen victim to the War of Currents between Thomas Edison and his electrical adversary, George Westinghouse. [...]

Harold P. Brown - hired by Edison to help him in his campaign to prove AC’s dangerousness - then brought in the first experimental subject: a 76-pound Newfoundland dog in a metal cage. The dog had been muzzled and had electrodes attached to one foreleg and one hind leg.

Brown connected the dog to the DC generator that Edison had loaned him and starting with 300 volts gradually increased the voltage to 1,000 volts. As the voltage increased, the observers noted, the dog’s yelping increased but it remained alive.

Having proven the safety of DC current, Brown disconnected the suffering animal from the DC generator and connected it to the AC generator with the remark, “We shall make him feel better.” (No word on whether he was twirling his mustache as he said so.)

Brown turned the voltage to 330, and the dog collapsed and died instantly.

The viewers were impressed, but Brown wasn’t done yet and brought in another dog. He said he was going to connect this one to the AC generator first. This, he said, would prove that the animal didn’t die because the shocks from the DC generator had weakened it.

Before he could accomplish this, however, an agent from the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals arrived and asked Brown to stop the experiment and spare the poor dog’s life. It took some convincing, but in the end Brown agreed to stay of execution. The second dog would die another day.

Although the regular newspapers loved this bit of theater, the trade magazine The Electrical Engineer claimed the experiment was unscientific. The magazine offered a terrible little poem about the proceedings:

Although the ASPCA might have brought his first experiment to a premature end, Brown was not deterred. He toured New York State for months, giving dog and pony shows before fascinated crowds, where he would electrocute cats, cows, calves, and well, dogs and ponies, using both direct and alternating currents. He paid young boys twenty-five cents apiece to round up stray animals to get fried.

The public watched — but wasn’t fooled, and continued to use alternating currents. Even the 1890 execution of William Kemmler in New York’s brand-spanking new AC electric chair failed to convince anyone that they were going to drop dead if they installed AC electricity in their homes. (Brown helped design the chair.) AC won the War of Currents hands-down.

The poor Newfoundland, having laid down its small life for the greater prosperity of Edison’s investors, died, unmourned, in vain.

(dall’imprescindibile sito Executed Today)

Harold P. Brown - hired by Edison to help him in his campaign to prove AC’s dangerousness - then brought in the first experimental subject: a 76-pound Newfoundland dog in a metal cage. The dog had been muzzled and had electrodes attached to one foreleg and one hind leg.

Brown connected the dog to the DC generator that Edison had loaned him and starting with 300 volts gradually increased the voltage to 1,000 volts. As the voltage increased, the observers noted, the dog’s yelping increased but it remained alive.

Having proven the safety of DC current, Brown disconnected the suffering animal from the DC generator and connected it to the AC generator with the remark, “We shall make him feel better.” (No word on whether he was twirling his mustache as he said so.)

Brown turned the voltage to 330, and the dog collapsed and died instantly.

The viewers were impressed, but Brown wasn’t done yet and brought in another dog. He said he was going to connect this one to the AC generator first. This, he said, would prove that the animal didn’t die because the shocks from the DC generator had weakened it.

Before he could accomplish this, however, an agent from the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals arrived and asked Brown to stop the experiment and spare the poor dog’s life. It took some convincing, but in the end Brown agreed to stay of execution. The second dog would die another day.

Although the regular newspapers loved this bit of theater, the trade magazine The Electrical Engineer claimed the experiment was unscientific. The magazine offered a terrible little poem about the proceedings:

The dog stood in the lattice box,

The wires around him led,

He knew not that electric shocks

So soon would strike him dead…

At last there came a deadly bolt,

The dog, O where was he?

Three hundred alternating volts,

Had burst his vicerae

The wires around him led,

He knew not that electric shocks

So soon would strike him dead…

At last there came a deadly bolt,

The dog, O where was he?

Three hundred alternating volts,

Had burst his vicerae

Although the ASPCA might have brought his first experiment to a premature end, Brown was not deterred. He toured New York State for months, giving dog and pony shows before fascinated crowds, where he would electrocute cats, cows, calves, and well, dogs and ponies, using both direct and alternating currents. He paid young boys twenty-five cents apiece to round up stray animals to get fried.

The public watched — but wasn’t fooled, and continued to use alternating currents. Even the 1890 execution of William Kemmler in New York’s brand-spanking new AC electric chair failed to convince anyone that they were going to drop dead if they installed AC electricity in their homes. (Brown helped design the chair.) AC won the War of Currents hands-down.

The poor Newfoundland, having laid down its small life for the greater prosperity of Edison’s investors, died, unmourned, in vain.

(dall’imprescindibile sito Executed Today)

Il 30 luglio del 1888, un cane Terranova di 76 libbre (circa 36 chilogrammi) fu elettrocutato (folgorato) in pubblico in una sala conferenza alla Columbia College School of Mines (oggi la Scuola di Ingegneria e Scienze Applicate alla Columbia University) di New York City. Il cane era un innocente caduto vittima della ‘guerra delle correnti’ combattuta da Thomas Edison (fautore della corrente continua) contro George Westinghouse (propugnatore della corrente alternata sulla base degli studi e delle scoperte di Nikola Tesla), suo avversario e diretto competitore sul nascente mercato dell’energia elettrica. [...]

Harold P. Brown - assunto da Edison per aiutarlo nella sua campagna denigratoria della corrente alternata - fu l’autore del primo esperimento in pubblico: la cavia era un grosso cane Terranova che era stato chiuso in una gabbia di metallo, con una museruola e gli elettrodi attaccati ad una zampa anteriore e ad una posteriore.

Brown collegò il cane al generatore di corrente continua di Edison e iniziò con 300 volt, aumentando gradualmente la tensione fino a 1.000 volt... Il cane soffriva terribilmente, lanciando alti guaiti, ma rimase vivo... Dopo aver dimostrato la sicurezza della corrente continua, Brown collegò l’animale al generatore di corrente alternata commentando, ‘Ora lo faremo stare meglio.’ (Non si sa se si sia lisciato i baffi pronunciando quella frase...). Brown girò la tensione a 330, e il cane crollò, morto all'istante.

Gli spettatori rimasero molto colpiti, ma Brown non era ancora soddisfatto e introdusse un altro cane. Disse che l’avrebbe collegato direttamente al generatore AC perchè bisognava dimostrare che il cane appena fritto non fosse morto per l’indebolimento dovuto alle scariche a corrente continua subite in precedenza... Ma prima che potesse ripetere l’esperimento intervenne un agente della Società Americana per la Prevenzione della Crudeltà verso gli Animali (ASPCA)... Brown, molto contrariato, accettò di fermare l'esperimento: il secondo cane sarebbe morto un altro giorno.

Anche se la maggioranza dei giornali lodarono questa farsa, la rivista The Electrical Engineer sostenne che l'esperimento non aveva nulla scientifico, e lo commentò con questa poesia:

Anche se l’ASPCA aveva boicottato il suo esperimento, Brown non si scoraggiò. Girò lo Stato di New York per mesi, incantando le folle con spettacoli nel corso dei quali fulminava gatti, mucche, vitelli, e pure cani e cavallini, mostrando la differente efficacia dei due sistemi di corrente. Brown pagava i ragazzi venticinque centesimi a testa perchè gli portassero animali randagi da friggere in pubblico!

Il pubblico osservava ma non si lasciò ingannare, e continuò ad usare la corrente alternata. E anche l’orribile fine che fecero fare a William Kemmler nel 1890 sulla nuova sedia elettrica di New York non riuscì a convincere nessuno che era meglio la corrente continua di Edison. Così Tesla e, soprattutto, Westinghouse vinsero al guerra, Edison si dedicò ad altro (p. e. cercando di registrare a suo nome il brevetto della macchina da presa cinematografica, inventata dal suo collaboratore William Kennedy Laurie Dickson) e Brown, intuito il business, passò a progettare sistemi per folgorare sempre meglio i condannati a morte.

Il povero Terranova, dopo aver dato la vita per la maggiore prosperità degli investitori di Edison, era morto, senza che nessuno lo piangesse, invano.

(Tentativo di traduzione italiana - un tanticchio creativa - di Bernart Bartleby)

Harold P. Brown - assunto da Edison per aiutarlo nella sua campagna denigratoria della corrente alternata - fu l’autore del primo esperimento in pubblico: la cavia era un grosso cane Terranova che era stato chiuso in una gabbia di metallo, con una museruola e gli elettrodi attaccati ad una zampa anteriore e ad una posteriore.

Brown collegò il cane al generatore di corrente continua di Edison e iniziò con 300 volt, aumentando gradualmente la tensione fino a 1.000 volt... Il cane soffriva terribilmente, lanciando alti guaiti, ma rimase vivo... Dopo aver dimostrato la sicurezza della corrente continua, Brown collegò l’animale al generatore di corrente alternata commentando, ‘Ora lo faremo stare meglio.’ (Non si sa se si sia lisciato i baffi pronunciando quella frase...). Brown girò la tensione a 330, e il cane crollò, morto all'istante.

Gli spettatori rimasero molto colpiti, ma Brown non era ancora soddisfatto e introdusse un altro cane. Disse che l’avrebbe collegato direttamente al generatore AC perchè bisognava dimostrare che il cane appena fritto non fosse morto per l’indebolimento dovuto alle scariche a corrente continua subite in precedenza... Ma prima che potesse ripetere l’esperimento intervenne un agente della Società Americana per la Prevenzione della Crudeltà verso gli Animali (ASPCA)... Brown, molto contrariato, accettò di fermare l'esperimento: il secondo cane sarebbe morto un altro giorno.

Anche se la maggioranza dei giornali lodarono questa farsa, la rivista The Electrical Engineer sostenne che l'esperimento non aveva nulla scientifico, e lo commentò con questa poesia:

Il cane si trovava nella gabbia

I cavi intorno a lui

Egli non sapeva che le scosse elettriche

Così in fretta l’avrebbero ucciso ...

Poi arrivò il fulmine mortale

Il cane, che ne era di lui?

Trecento volt alternati

Gli avevano bruciato le viscere.

I cavi intorno a lui

Egli non sapeva che le scosse elettriche

Così in fretta l’avrebbero ucciso ...

Poi arrivò il fulmine mortale

Il cane, che ne era di lui?

Trecento volt alternati

Gli avevano bruciato le viscere.

Anche se l’ASPCA aveva boicottato il suo esperimento, Brown non si scoraggiò. Girò lo Stato di New York per mesi, incantando le folle con spettacoli nel corso dei quali fulminava gatti, mucche, vitelli, e pure cani e cavallini, mostrando la differente efficacia dei due sistemi di corrente. Brown pagava i ragazzi venticinque centesimi a testa perchè gli portassero animali randagi da friggere in pubblico!

Il pubblico osservava ma non si lasciò ingannare, e continuò ad usare la corrente alternata. E anche l’orribile fine che fecero fare a William Kemmler nel 1890 sulla nuova sedia elettrica di New York non riuscì a convincere nessuno che era meglio la corrente continua di Edison. Così Tesla e, soprattutto, Westinghouse vinsero al guerra, Edison si dedicò ad altro (p. e. cercando di registrare a suo nome il brevetto della macchina da presa cinematografica, inventata dal suo collaboratore William Kennedy Laurie Dickson) e Brown, intuito il business, passò a progettare sistemi per folgorare sempre meglio i condannati a morte.

Il povero Terranova, dopo aver dato la vita per la maggiore prosperità degli investitori di Edison, era morto, senza che nessuno lo piangesse, invano.

(Tentativo di traduzione italiana - un tanticchio creativa - di Bernart Bartleby)

Bernart Bartleby - 2014/9/15 - 21:11

×

![]()

Note for non-Italian users: Sorry, though the interface of this website is translated into English, most commentaries and biographies are in Italian and/or in other languages like French, German, Spanish, Russian etc.

Parole e musica di Laurie Anderson

Nel quadruplo “United States, Live”

Una spoken-song dedicata allo scienziato serbo, naturalizzato statunitense, Nikola Tesla (1856-1943).

Tesla fu protagonista indiscusso degli studi sull’elettromagnetismo ed il suo lavoro teorico è alla base del moderno sistema elettrico a corrente alternata (AC), ma nonostante il suo genio indiscusso lo scienziato, pur sempre un immigrato e inoltre considerato un eccentrico quando non un folle, dovette scontrarsi con quel mulo ignorante di Thomas Edison, un uomo incolto, presuntuoso e sprezzante della scienza che pure ancora oggi è considerato “l’inventore” per antonomasia, un eroe per tutti gli americani. Edison, che era fautore del sistema a corrente continua e che sperava con quello di tirar su con un bel po’ di soldi, dichiarò guerra a Tesla e a quanti lo sostenevano (p. e. George Westinghouse) e iniziò una orrida campagna di pubblicità negativa girando gli States a folgorare animali vivi – dai cani agli elefanti, si veda la canzone Topsy's Revenge - per dimostrare quanto fosse pericolosa la corrente alternata di Tesla, buona solo per arrostire, friggere, elettrocutare, dare la morte. Di fatto le dimostrazioni di Edison contribuirono proprio all’avvento della sedia elettrica come strumento per l’eliminazione dei condannati alla pena capitale: fu infatti Edison a portare a termine il progetto che inizialmente era stato affidato a Westinghouse il quale però, mangiata la foglia, non aveva voluto proseguirlo, intuendone le implicazioni negative.

La prima vittima umana della sedia elettrica fu il femminicida William Kemmler nel 1890: 8 minuti di terribile agonia. Westinghouse, riferendosi all'esecuzione, affermò che “Sarebbe riuscita meglio se avessero usato un'ascia”.

E mentre Edison, abile amministratore di se stesso, accumulò immeritata fama e brevetti (su invenzioni in gran parte opera di altri), Nikola Tesla morì in totale povertà e pressochè dimenticato.