The year, it is 1927, an' the day is the third day of May;

Town is the city called Boston, an' our address this dark Dedham jail.

To your honor, the Governor Fuller, to the council of Massachussetts state,

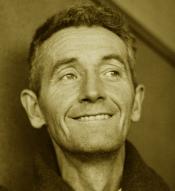

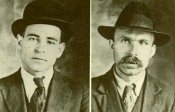

We, Bartolomeo Vanzetti, an' Nicola Sacco, do say:

Confined to our jail here at Dedham an' under the sentence of death,

We pray you do exercise your powers an' look at the facts of our case.

We do not ask you for a pardon, for a pardon would admit of our guilt;

Since we are both innocent workers, we have no guilt to admit.

We are both born by parents in Italy, can't speak English too well;

Our friends of labor are writin' these words, back of the barsin our cell.

Our friends say if we speak too plain, sir, we may turn your feelings away,

Widen these canyons between us, but we risk our life to talk plain.

We think, sir, that each human bein' is in close touch with all of man's kind,

We think, sir, that each human bein' knows right from the wrong in his mind.

We talk to you here as a man, sir, even knowing our opinions divide;

We didn't kill the guards at South Braintree, nor dream of such a terrible crime.

We call your eye to this fact, sir, we work with our hand and our brain;

These robberies an' killings, were done, sir, by professional bandit men,

Sacco has been a good cutter, Mrs. Sacco their money has saved;

I, Vanzetti, l could have saved money, but I gave it as fast as received.

l'm a dreamer, a speaker, an' a writer; I fight on the working folks' side.

Sacco is Boston's fastest shoe trimmer, and he talks to the husbands and wives.

We hunted your land, and we found it, hoped we'd find freedom of mind,

Built up your land, this Land of the Free, an' this is what we come to find.

If we was those killers, good Governor, we'd not be so dumb and so blind

To pass out our handbills and make workers' speeches, out here by the scene of the crime.

Those fifteen thousands of dollars the lawyers and judge said we took,

Do we, sir, dress up like two gentlemen with that much in our pocketbook?

Our names are on the long list of radicals of the Federal Government, sir,

They said that we needed watching as we peddled our literature.

Judge Thayer's mind's made up, sir, when we walked into the court;

Well, he called us anarchistic bastards, said lots of other things worse.

They brought people down there to Brockton to look through the bars of our cell,

Made us act out the motions of the killers, and still not so many could tell.

Before the trial ever started, the jury foreman did say,

An' he cussed us an' said, "Damn they, well, they'd ought to hang anyway."

Our fatal mistake was carryin' our guns, about which we had to tell lies

To keep the police from raiding the homes of workers believing like us.

A labor paper, or a picture, a letter from a radical friend,

An old cheap gun like you keep around home, would torture good women and men.

We all feared deporting and whipping, torments to make us confess

The place where the workers are meeting, the house, your name, and address.

Well. the officers said we feared something which they called a consciousness of guilt.

We was afraid of wreckin' more homes, and seein' more workers' blood spilt.

Well, the very first question they asked us was not about killing the clerks,

But things about our labor movement, and how our trade union works.

Oh, how could our jury see clearly, when the lawyers, and judges, and cops

Called us low type Italians, said we looked just like regular wops,

Draft dodgers, gun packers, anarchists, these vulgar sounding names,

Blew dust in the eyes of jurors, the crowd in the courtroom the same.

We do not believe, sir, that torture, beatings, and killings and pains

Will lift man's eyes to a highest of view an' break his bilbos and chains.

We believe that you must struggle for freedom before your freedom you'll gain,

Freedom from fear, sir, and greed, sir, and your freedom to think higher things.

This fight, sir, is not a new battle, we did not make it last night,

'Twas fought by Godwin, Shelly, Pisacane, Tolstoy and Christ;

It's bigger than the atoms an' the sands of the desert, planets that roll in the sky;

Till workers get rid of their robbers, well, it's worse, sir, to live than to die.

Your Excellency, we're not askin' pardon but askin' to be set free,

With liberty, and pride, sir, and honor, and a pardon we will not receive.

A pardon you given to criminals who've broken the laws of the land;

We don't ask you for pardon, sir, because we are innocent men.

Well, if you shake your head "no", dear Governor, of course, our doom it is sealed.

We hold up our heads like two sons of men, seven years in these cells of steel.

We walk down this corridor to death, sir, like workers have walked it before,

But we'll work in our working class struggle if we live a thousand lives more.

Town is the city called Boston, an' our address this dark Dedham jail.

To your honor, the Governor Fuller, to the council of Massachussetts state,

We, Bartolomeo Vanzetti, an' Nicola Sacco, do say:

Confined to our jail here at Dedham an' under the sentence of death,

We pray you do exercise your powers an' look at the facts of our case.

We do not ask you for a pardon, for a pardon would admit of our guilt;

Since we are both innocent workers, we have no guilt to admit.

We are both born by parents in Italy, can't speak English too well;

Our friends of labor are writin' these words, back of the barsin our cell.

Our friends say if we speak too plain, sir, we may turn your feelings away,

Widen these canyons between us, but we risk our life to talk plain.

We think, sir, that each human bein' is in close touch with all of man's kind,

We think, sir, that each human bein' knows right from the wrong in his mind.

We talk to you here as a man, sir, even knowing our opinions divide;

We didn't kill the guards at South Braintree, nor dream of such a terrible crime.

We call your eye to this fact, sir, we work with our hand and our brain;

These robberies an' killings, were done, sir, by professional bandit men,

Sacco has been a good cutter, Mrs. Sacco their money has saved;

I, Vanzetti, l could have saved money, but I gave it as fast as received.

l'm a dreamer, a speaker, an' a writer; I fight on the working folks' side.

Sacco is Boston's fastest shoe trimmer, and he talks to the husbands and wives.

We hunted your land, and we found it, hoped we'd find freedom of mind,

Built up your land, this Land of the Free, an' this is what we come to find.

If we was those killers, good Governor, we'd not be so dumb and so blind

To pass out our handbills and make workers' speeches, out here by the scene of the crime.

Those fifteen thousands of dollars the lawyers and judge said we took,

Do we, sir, dress up like two gentlemen with that much in our pocketbook?

Our names are on the long list of radicals of the Federal Government, sir,

They said that we needed watching as we peddled our literature.

Judge Thayer's mind's made up, sir, when we walked into the court;

Well, he called us anarchistic bastards, said lots of other things worse.

They brought people down there to Brockton to look through the bars of our cell,

Made us act out the motions of the killers, and still not so many could tell.

Before the trial ever started, the jury foreman did say,

An' he cussed us an' said, "Damn they, well, they'd ought to hang anyway."

Our fatal mistake was carryin' our guns, about which we had to tell lies

To keep the police from raiding the homes of workers believing like us.

A labor paper, or a picture, a letter from a radical friend,

An old cheap gun like you keep around home, would torture good women and men.

We all feared deporting and whipping, torments to make us confess

The place where the workers are meeting, the house, your name, and address.

Well. the officers said we feared something which they called a consciousness of guilt.

We was afraid of wreckin' more homes, and seein' more workers' blood spilt.

Well, the very first question they asked us was not about killing the clerks,

But things about our labor movement, and how our trade union works.

Oh, how could our jury see clearly, when the lawyers, and judges, and cops

Called us low type Italians, said we looked just like regular wops,

Draft dodgers, gun packers, anarchists, these vulgar sounding names,

Blew dust in the eyes of jurors, the crowd in the courtroom the same.

We do not believe, sir, that torture, beatings, and killings and pains

Will lift man's eyes to a highest of view an' break his bilbos and chains.

We believe that you must struggle for freedom before your freedom you'll gain,

Freedom from fear, sir, and greed, sir, and your freedom to think higher things.

This fight, sir, is not a new battle, we did not make it last night,

'Twas fought by Godwin, Shelly, Pisacane, Tolstoy and Christ;

It's bigger than the atoms an' the sands of the desert, planets that roll in the sky;

Till workers get rid of their robbers, well, it's worse, sir, to live than to die.

Your Excellency, we're not askin' pardon but askin' to be set free,

With liberty, and pride, sir, and honor, and a pardon we will not receive.

A pardon you given to criminals who've broken the laws of the land;

We don't ask you for pardon, sir, because we are innocent men.

Well, if you shake your head "no", dear Governor, of course, our doom it is sealed.

We hold up our heads like two sons of men, seven years in these cells of steel.

We walk down this corridor to death, sir, like workers have walked it before,

But we'll work in our working class struggle if we live a thousand lives more.

envoyé par Adriana e Riccardo - 6/1/2006 - 14:58

Langue: italien

Traduzione integrale italiana di Riccardo Venturi

4/9 settembre 2014

Due parole del traduttore. La lunghissima ballata basata sull'estrema lettera di Vanzetti al governatore Fuller ha richiesto giorni di lavoro, e non solo per le sue dimensioni, ma anche per il particolare linguaggio usato. Per la sua non buona conoscenza dell'inglese scritto, Vanzetti si fece effettivamente redigere la lettera dai compagni di prigionia; i quali, dovendo rivolgersi al governatore di uno Stato, usarono quella mistura di inglese burocratico e "high-flown" (arcaismi ecc.) unita a volgarismi (tipo "cussed" per "cursed", o l'uso regolare del singolare "was" per "were" ["we was"] ecc.) e grafie scorrette (tipo "Shelly" per il poeta Shelley). Nulla di tutto questo può essere riprodotto in italiano in modo adeguato; ho quindi scelto una traduzione in linguaggio piano e corretto, interpretando a volte alcuni passi che, tradotti letteralmente, non avrebbero avuto alcun senso. Nella ballata è notevole la menzione di Carlo Pisacane tra i grandi rivoluzionari dell'umanità; si ricordi che la figura di Pisacane era stata resa nota con la traduzione della "Spigolatrice di Sapri" che aveva fatto un grande poeta americano, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Curiosa anche la menzione di Gesù Cristo, molto "americana" in una lettera scritta, o fatta scrivere, da un anarchico. Ma è autentica.

4/9 settembre 2014

Due parole del traduttore. La lunghissima ballata basata sull'estrema lettera di Vanzetti al governatore Fuller ha richiesto giorni di lavoro, e non solo per le sue dimensioni, ma anche per il particolare linguaggio usato. Per la sua non buona conoscenza dell'inglese scritto, Vanzetti si fece effettivamente redigere la lettera dai compagni di prigionia; i quali, dovendo rivolgersi al governatore di uno Stato, usarono quella mistura di inglese burocratico e "high-flown" (arcaismi ecc.) unita a volgarismi (tipo "cussed" per "cursed", o l'uso regolare del singolare "was" per "were" ["we was"] ecc.) e grafie scorrette (tipo "Shelly" per il poeta Shelley). Nulla di tutto questo può essere riprodotto in italiano in modo adeguato; ho quindi scelto una traduzione in linguaggio piano e corretto, interpretando a volte alcuni passi che, tradotti letteralmente, non avrebbero avuto alcun senso. Nella ballata è notevole la menzione di Carlo Pisacane tra i grandi rivoluzionari dell'umanità; si ricordi che la figura di Pisacane era stata resa nota con la traduzione della "Spigolatrice di Sapri" che aveva fatto un grande poeta americano, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Curiosa anche la menzione di Gesù Cristo, molto "americana" in una lettera scritta, o fatta scrivere, da un anarchico. Ma è autentica.

LA LETTERA DI VANZETTI

L'anno è il 1927, il giorno il tre di maggio,

la città si chiama Boston, il nostro indirizzo è questo tetro carcere di Dedham.

A Vostro Onore, governatore Fuller, e al governo dello stato del Massachusetts,

Noi, Bartolomeo Vanzetti e Nicola Sacco, diciamo quanto segue:

Rinchiusi qua in prigione a Dedham e sotto sentenza di morte

Vi preghiamo di esercitare i Vostri poteri e considerare i fatti del nostro caso.

Non Vi chiediamo la grazia, perché una grazia sarebbe ammettere la nostra colpevolezza;

Poiché entrambi siamo lavoratori innocenti, non abbiamo nessuna colpa da ammettere.

Entrambi siamo nati da famiglie italiane e non sappiamo l'inglese troppo bene;

queste parole le stanno scrivendo i nostri compagni di pena, in cella dietro le sbarre.

I nostri amici dicono che parlare troppo chiaro potrebbe contrariarVi, Signore,

e ampliare ancor più il divario tra di noi; ma, parlando chiaro, noi rischiamo la vita.

Pensiamo, Signore, che ogni essere umano sia a stretto contatto con tutta l'umanità,

pensiamo, Signore, che ogni essere umano sappia distinguere il bene dal male dentro di sé.

Vi parliamo qui come ad un uomo, Signore, pur sapendo che abbiamo opinioni diverse;

Non abbiamo ucciso le guardie a South Braintree, né mai abbiamo immaginato un crimine così tremendo.

Richiamiamo la Vostra attenzione, Signore, su questo fatto: noi lavoriamo manualmente e intellettualmente;

queste rapine e questi omicidi, Signore, sono stati commessi da banditi di professione.

Sacco è stato un bravo calzolaio, e la signora Sacco ha messo da parte i loro guadagni;

Io, Vanzetti, avrei potuto risparmiare denaro, ma lo donavo non appena lo guadagnavo.

Sono un idealista, un oratore e uno scrittore; combatto dalla parte dei lavoratori.

Sacco è il più veloce calzolaio di Boston, e tiene discorsi alle famiglie.

Abbiamo cercato il vostro paese, e lo abbiamo trovato; speravamo di trovare libertà di pensiero,

abbiamo edificato il vostro paese, questo Paese di Libertà; questo eravamo venuti a cercare.

Se fossimo stati quegli assassini, signor Governatore, non saremmo stati così stupidi e ciechi

da far circolare i nostri volantini e parlare ai lavoratori giusto là sulla scena del crimine.

Quanto a quei quindicimila dollari che gli avvocati e il giudice hanno detto che abbiamo preso,

Signore, secondo Voi siamo vestiti da gentiluomini, con tutti quei soldi in tasca?

I nostri nomi sono nella lunga lista dei sovversivi del governo federale, Signore.

Dicevano che dovevamo essere tenuti sotto controllo mentre noi distribuivamo i nostri opuscoli porta a porta.

Il giudice Thayer aveva già deciso tutto, signore, da quando avevamo messo piede in aula;

Beh, ci chiamò bastardi anarchici e disse un sacco di cose anche peggiori.

Portarono delle persone quaggiù a Brockton per guardare tra le sbarre della nostra cella,

ci fecero ripetere i gesti degli assassini, eppure non molti seppero dire qualcosa.

Ancor prima che cominciasse il processo, il presidente della giuria disse,

ci maledisse, e disse: “Accidenti a loro, comunque dovrebbero essere impiccati.”

Abbiamo fatto un errore fatale, portarci dietro le pistole e aver dovuto mentire su di esse

per evitare che la polizia entrasse nelle case dei lavoratori che la pensano come noi.

Una tessera sindacale, una foto, una lettera da un amico anarchico

o una vecchia pistola a buon mercato come quella che chiunque ha in casa, potrebbero far torturare brav'uomini e brave donne.

Tutti noi temevamo di essere deportati e frustati, torture per farci confessare

il posto dove i lavoratori si riuniscono, la casa, i nomi, gli indirizzi.

I funzionari di polizia dicevano che avevamo paura di qualcosa che loro chiamano senso di colpa.

Noi avevamo paura di rovinare ancor più famiglie e di veder versare il sangue di ancor più lavoratori.

Beh, la primissima domanda che ci fecero non fu sull'assassinio degli impiegati,

ma cose sul nostro movimento sindacale e su come funziona il nostro sindacato.

Come poteva la giuria vederci chiaro, se gli avvocati, i giudici e i poliziotti

ci chiamavano italiani di bassa lega e dicevano che sembravamo i soliti italiani di merda,

renitenti alla leva, sempre con la pistola dietro, anarchici; questi epiteti volgari

misero fumo negli occhi ai giurati, e lo stesso alla folla che seguiva il processo in aula.

Noi non crediamo, signore, che la tortura, le botte, gli assassinii e le pene

eleveranno gli sguardi dell'umanità a una visione più alta, e spezzeranno le sue spade e le sue catene.

Noi crediamo che si debba combattere per la libertà prima che la si ottenga,

la libertà dalla paura, signore, e dalla cupidigia, e la libertà di pensare cose più elevate.

Questa lotta, signore, non è nuova. Non l'abbiamo fatta noi l'altra sera,

ma l'hanno fatta Godwin, Shelley, Pisacane, Tolstoj e Gesù Cristo;

è più grande degli atomi e delle sabbie del deserto, e dei pianeti che ruotano nel cielo;

finché i lavoratori non si libereranno di chi li deruba, signore, sarà peggio vivere che morire.

Vostra Eccellenza, noi non stiamo chiedendo la grazia, bensì di essere messi in libertà,

da uomini liberi, fieri e onorati, signore, e non intendiamo ricevere alcuna grazia.

La grazia la si dà ai criminali che hanno infranto le leggi della Nazione;

noi non Vi chiediamo la grazia, signore, perché siamo innocenti.

Bene, se Voi scuoterete la testa e direte “no”, signor Governatore, naturalmente il nostro destino sarà segnato.

Noi teniamo la testa alta come uomini, rinchiusi da sette anni in questa cella d'acciaio.

Percorreremo quel corridoio fino alla morte, signore, come altri lavoratori prima di noi lo hanno percorso,

ma agiremo per la lotta di classe dei lavoratori, dovessimo vivere mille anni ancora.

L'anno è il 1927, il giorno il tre di maggio,

la città si chiama Boston, il nostro indirizzo è questo tetro carcere di Dedham.

A Vostro Onore, governatore Fuller, e al governo dello stato del Massachusetts,

Noi, Bartolomeo Vanzetti e Nicola Sacco, diciamo quanto segue:

Rinchiusi qua in prigione a Dedham e sotto sentenza di morte

Vi preghiamo di esercitare i Vostri poteri e considerare i fatti del nostro caso.

Non Vi chiediamo la grazia, perché una grazia sarebbe ammettere la nostra colpevolezza;

Poiché entrambi siamo lavoratori innocenti, non abbiamo nessuna colpa da ammettere.

Entrambi siamo nati da famiglie italiane e non sappiamo l'inglese troppo bene;

queste parole le stanno scrivendo i nostri compagni di pena, in cella dietro le sbarre.

I nostri amici dicono che parlare troppo chiaro potrebbe contrariarVi, Signore,

e ampliare ancor più il divario tra di noi; ma, parlando chiaro, noi rischiamo la vita.

Pensiamo, Signore, che ogni essere umano sia a stretto contatto con tutta l'umanità,

pensiamo, Signore, che ogni essere umano sappia distinguere il bene dal male dentro di sé.

Vi parliamo qui come ad un uomo, Signore, pur sapendo che abbiamo opinioni diverse;

Non abbiamo ucciso le guardie a South Braintree, né mai abbiamo immaginato un crimine così tremendo.

Richiamiamo la Vostra attenzione, Signore, su questo fatto: noi lavoriamo manualmente e intellettualmente;

queste rapine e questi omicidi, Signore, sono stati commessi da banditi di professione.

Sacco è stato un bravo calzolaio, e la signora Sacco ha messo da parte i loro guadagni;

Io, Vanzetti, avrei potuto risparmiare denaro, ma lo donavo non appena lo guadagnavo.

Sono un idealista, un oratore e uno scrittore; combatto dalla parte dei lavoratori.

Sacco è il più veloce calzolaio di Boston, e tiene discorsi alle famiglie.

Abbiamo cercato il vostro paese, e lo abbiamo trovato; speravamo di trovare libertà di pensiero,

abbiamo edificato il vostro paese, questo Paese di Libertà; questo eravamo venuti a cercare.

Se fossimo stati quegli assassini, signor Governatore, non saremmo stati così stupidi e ciechi

da far circolare i nostri volantini e parlare ai lavoratori giusto là sulla scena del crimine.

Quanto a quei quindicimila dollari che gli avvocati e il giudice hanno detto che abbiamo preso,

Signore, secondo Voi siamo vestiti da gentiluomini, con tutti quei soldi in tasca?

I nostri nomi sono nella lunga lista dei sovversivi del governo federale, Signore.

Dicevano che dovevamo essere tenuti sotto controllo mentre noi distribuivamo i nostri opuscoli porta a porta.

Il giudice Thayer aveva già deciso tutto, signore, da quando avevamo messo piede in aula;

Beh, ci chiamò bastardi anarchici e disse un sacco di cose anche peggiori.

Portarono delle persone quaggiù a Brockton per guardare tra le sbarre della nostra cella,

ci fecero ripetere i gesti degli assassini, eppure non molti seppero dire qualcosa.

Ancor prima che cominciasse il processo, il presidente della giuria disse,

ci maledisse, e disse: “Accidenti a loro, comunque dovrebbero essere impiccati.”

Abbiamo fatto un errore fatale, portarci dietro le pistole e aver dovuto mentire su di esse

per evitare che la polizia entrasse nelle case dei lavoratori che la pensano come noi.

Una tessera sindacale, una foto, una lettera da un amico anarchico

o una vecchia pistola a buon mercato come quella che chiunque ha in casa, potrebbero far torturare brav'uomini e brave donne.

Tutti noi temevamo di essere deportati e frustati, torture per farci confessare

il posto dove i lavoratori si riuniscono, la casa, i nomi, gli indirizzi.

I funzionari di polizia dicevano che avevamo paura di qualcosa che loro chiamano senso di colpa.

Noi avevamo paura di rovinare ancor più famiglie e di veder versare il sangue di ancor più lavoratori.

Beh, la primissima domanda che ci fecero non fu sull'assassinio degli impiegati,

ma cose sul nostro movimento sindacale e su come funziona il nostro sindacato.

Come poteva la giuria vederci chiaro, se gli avvocati, i giudici e i poliziotti

ci chiamavano italiani di bassa lega e dicevano che sembravamo i soliti italiani di merda,

renitenti alla leva, sempre con la pistola dietro, anarchici; questi epiteti volgari

misero fumo negli occhi ai giurati, e lo stesso alla folla che seguiva il processo in aula.

Noi non crediamo, signore, che la tortura, le botte, gli assassinii e le pene

eleveranno gli sguardi dell'umanità a una visione più alta, e spezzeranno le sue spade e le sue catene.

Noi crediamo che si debba combattere per la libertà prima che la si ottenga,

la libertà dalla paura, signore, e dalla cupidigia, e la libertà di pensare cose più elevate.

Questa lotta, signore, non è nuova. Non l'abbiamo fatta noi l'altra sera,

ma l'hanno fatta Godwin, Shelley, Pisacane, Tolstoj e Gesù Cristo;

è più grande degli atomi e delle sabbie del deserto, e dei pianeti che ruotano nel cielo;

finché i lavoratori non si libereranno di chi li deruba, signore, sarà peggio vivere che morire.

Vostra Eccellenza, noi non stiamo chiedendo la grazia, bensì di essere messi in libertà,

da uomini liberi, fieri e onorati, signore, e non intendiamo ricevere alcuna grazia.

La grazia la si dà ai criminali che hanno infranto le leggi della Nazione;

noi non Vi chiediamo la grazia, signore, perché siamo innocenti.

Bene, se Voi scuoterete la testa e direte “no”, signor Governatore, naturalmente il nostro destino sarà segnato.

Noi teniamo la testa alta come uomini, rinchiusi da sette anni in questa cella d'acciaio.

Percorreremo quel corridoio fino alla morte, signore, come altri lavoratori prima di noi lo hanno percorso,

ma agiremo per la lotta di classe dei lavoratori, dovessimo vivere mille anni ancora.

×

![]()

Testo e musica di Woody Guthrie

Lyrics and music by Woody Guthrie

Questa canzone, assieme ad altre, fu commissionata a Woody Guthrie tra il 1945 e il 1947 da Moses Asch

2. I Just Want To Sing Your Name

3. Old Judge Thayer

4. Red Wine

5. Root Hog And Die

6. Suassos Lane

7. Two Good Men

8. Vanzetti's Letter

9. Vanzetti's Rock

10. We Welcome To Heaven

11. You Souls Of Boston

12. Sacco's Letter To His Son (Pete Seeger)

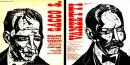

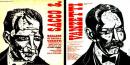

Ballads of Sacco and Vanzetti è una raccolta di ballate folk scritte e interpretate dal cantautore americano Woody Guthrie, ispirate alla vicenda di Sacco e Vanzetti. Le ballate furono commissionate da Moses Asch nel 1945, e registrate tra il 1946 e il 1947. Guthrie non completò mai il progetto, e si ritenne insoddisfatto dal lavoro, sebbene suo figlio Arlo Guthrie, a sua volta cantautore professionista, giudicò le ballate del ciclo "Sacco e Vanzetti", tra le migliori mai composte da suo padre. Una canzone inedita, "Sacco's Letter To His Son", fu registrata da Pete Seeger per il progetto.

Ballads of Sacco & Vanzetti is a set of ballad songs, written and performed by Woody Guthrie, related to the trial, conviction and execution of Sacco and Vanzetti. The series was commissioned by Moe Asch in 1945 and recorded in 1946 and 1947. Guthrie never completed the project and was unsatisfied by the result. The project was released later in its abandoned form by Asch. An unreleased track, "Sacco's Letter To His Son" was recorded by Pete Seeger for the project.

Moses Asch was the founder/head of Folkways Records, which made available the music of Leadbelly, Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger. Without this music, what would Dylan have been? Tom Piazza, writing in the April 1995 issue of The Atlantic Monthly, gives a history of Folkway Records and of Moses Asch:

"Born in Poland in 1905, Asch arrived in the United States when he was ten years old. He spent a few years in German in the early 1920s, studying electronics, but by the time he found himself back in New York, in 1926, his interest in American folk music had been stirred by his discovery, in a bookstall on a Paris quay, of John Lomax's book Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads.

"While building radio equipment and arranging sound systems for clients ranging from Yiddish theaters to burlesque houses on the Lower East Side, Asch came up with the idea of creating a record label to document the music that the larger commercial labels tended to leave alone.

"His idea was nourished not only by a love for the music itself but also by a brand of leftist populism in which folk expression was a voice for the disenfranchised. By taste and political conviction, Asch was attracted to the raw and the otherwise unheard.

"In the early 1940s he started two record companies, Asch and Disc. Both failed. Before folding them Asch recorded his most important artists -- the singer and songwriter Woody Guthrie and great twelve-string guitarist and singer Leadbelly.

"In 1947 Asch started Folkways, and this time it worked. Until his death, in 1986, Asch was Folkways' president, chief financial officer, talent scout, audio engineer, and sometimes shipping clerk."

"In 1987, the Smithsonian bought out Folkways, agreeing to keep all 2,200 Folkways albums in print. By writing or calling Smithsonian/Folkways (414 Hungerford Drive, Suite 444, Rockville, MD 20850; 301-443-2314 or fax 301-443-1819) one can order any Folkways title and receive a high-quality cassette, along with the original descriptive notes, for about $11. A free copy of the The Whole Folkways Catalogue, which lists every title, should be ordered first.

"It is," concludes Piazza in The Atlantic Monthly, "the definitive guide to Asch's bold, eccentric, priceless legacy."

It was an indirect impact on Dylan, but very major.

radiohazak.com