Terra da fraternidade,

O povo é quem mais ordena

Dentro de ti, ó cidade.

Dentro de ti, ó cidade

O povo é quem mais ordena,

Terra da fraternidade,

Grândola, vila morena.

Em cada esquina um amigo,

Em cada rosto igualdade,

Grândola, vila morena

Terra da fraternidade.

Terra da fraternidade,

Grândola, vila morena

Em cada rosto igualdade

O povo é quem mais ordena.

À sombra duma azinheira

Que já não sabia a idade

Jurei ter por companheira

Grândola, a tua vontade.

Grândola a tua vontade

Jurei ter por companheira

À sombra duma azinheira

Que já não sabia a idade.

Riccardo Venturi [2003; rev. 2004]

Grândola, città dei Mori

terra di fratellanza

è il popolo che più comanda

dentro di te, o città.

Dentro di te, o città

è il popolo che più comanda

terra di fratellanza,

Grândola città dei Mori.

A ogni angolo un amico,

su ogni volto l'uguaglianza

Grândola città dei Mori

terra di fratellanza

terra di fratellanza,

Grândola città dei Mori

su ogni volto l'uguaglianza,

è il popolo che più comanda.

Ed all'ombra d'una sughera

che non sa più quanti anni ha

giurai d'aver per compagna,

Grândola, la tua volontà.

Grândola, la tua volontà

giurai d'aver per compagna

all'ombra d'una sughera

che non sa più quanti anni ha.

Grandola, città moresca

Terra di fraternità

Il tuo popolo governa

Dentro di te, o città

Dentro di te, o città

Il tuo popolo governa

Terra di fraternità

Grandola, città moresca

In ogni angolo un amico

Ogni viso l’uguaglianza

Il tuo popolo governa

Terra di fraternità

Terra di fraternità

Grandola, città moresca

Ogni viso l’uguaglianza

Il tuo popolo governa

Sotto l’ombra di un gran leccio

Di cui non si sa l’età

Ho giurato comunanza

Grandola, tua volontà

Grandola, tua volontà

Ho giurato comunanza

Sotto l’ombra di un gran leccio

Di cui non si sa l’età.

Contributed by Luke Atreides - 2024/4/25 - 22:46

Riccardo Venturi [2003]

Grândola, ville des Mores

terre de fraternité

c'est le peuple qui s'impose

dans toi, ô vieille cité.

Dans toi, ô vieille cité

c'est le peuple qui s'impose

terre de fraternité,

Grândola, ville des Mores.

A chaque coin, y a un ami,

dans les yeux l'égalité,

Grândola, ville des Mores

terre de fraternité.

Terre de fraternité

Grândola, ville des Mores,

dans les yeux l'égalité,

C'est le peuple qui s'impose.

C'est à l'ombre d'un chêne-liège

ignorant du tout son âge

que j'ai pris ta volonté

comme compagne de voyage.

Comme compagne de voyage

oui, j'ai pris ta volonté

Grândola, sous un chêne-liège

ignorant du tout son âge.

Jadis (L. Trans.)

Grândola, ma ville brune

Belle terre fraternelle

C'est le peuple qui dispose

Et règne sur toi, ma ville

Au travers de toi, ma ville

Ton peuple règne et dispose

Belle terre fraternelle

Grândola, ma ville brune.

Partout un ami se lève

Tous égaux sont les visages

Grândola, ma ville brune

Belle terre fraternelle.

Belle terre fraternelle,

Grândola, ma ville brune

Tous égaux sont les visages

C'est le peuple qui dispose.

Grândola, à l'ombre fraîche

D'un chêne vert séculaire

J'ai juré que pour compagne

Ta volonté serait mienne.

Ta volonté sera mienne

Et tu seras ma compagne

Car je l'ai juré sous l'ombre

D'un chêne vert séculaire.

Sung by Joan Baez

Grândola, swarthy town,

Land of brotherhood

'Tis the people who command the most

Inside of you, o city.

Inside of you, o city

'Tis the people who command the most

Land of brotherhood

Grândola, swarthy town.

On every corner, a friend

In every face, equality

Grândola, swarthy town

Land of brotherhood.

Land of brotherhood

Grândola, swarthy town.

In every face, equality

On every corner, a friend

'Tis the people who command the most.

In the shadow of a cork oak

That none now knows its age,

I swore to have your will

Grândola, as my companion.

Grândola, as my companion

Did I swear to have your will

In the shadow of a cork oak

That none now knows its age.

Contributed by Alessandro - 2006/5/23 - 23:05

Franz-Josef Degenhardt [1975]

Album / Albumi: Mit aufrechtem Gang

Stadt der Sonne, Stadt der Brüder

Grândola, vila morena [1]

Stadt der Sonne, Stadt der Brüder,

Grândola, vila morena,

Grândola, du Stadt der Lieder.

Grândola, du Stadt der Lieder,

auf den Plätzen, in den Straßen

gehen Freunde, stehen Brüder,

Grândola gehört den Massen.

Grândola, vila morena,

viele Hände, die dich fassen,

Solidarität und Freiheit

geht der Ruf durch deine Straßen.

Geht das Lied durch deine Straßen,

gleich und gleich sind uns're Schritte,

Grândola, vila morena

gleich und gleich durch deine Mitte.

Deine Kraft und euer Wille

sind so alt wie uns're Träume,

Grândola, vila morena

alt wie deine Schattenbäume.

Alt wie deine Schattenbäume

Grândola, die Stadt der Brüder,

Grândola, und deine Lieder

sind jetzt nicht mehr nur noch Träume.

di Riccardo Venturi, 1-3-2024

Grândola, vila morena,

Città del sole, città dei fratelli,

Grândola, vila morena,

Grândola, città delle canzoni.

Grândola, città delle canzoni,

Nelle piazze, nelle strade

vanno amici, stanno fratelli,

Grândola appartiene alle masse.

Grândola, vila morena,

Tante mani che ti abbracciano,

Solidarietà e libertà,

Va il grido per le tue strade,

Va la canzone per le tue strade,

Tutti uguali sono i nostri passi,

Grândola, vila morena

Tutti uguali in mezzo a te.

La tua forza e la vostra volontà

Sono antiche come i nostri sogni,

Grândola, vila morena,

Antiche come i tuoi alberi ombrosi.

Antiche come i tuoi alberi ombrosi,

Grândola, città dei fratelli,

Grândola, e le tue canzoni

Ora non sono più soltanto sogni.

Grandola braune Stadt,

Land der Brüderlichkeit,

Das Volk regiert,

In Dir, oh Stadt.

In Dir, oh Stadt,

Regiert das Volk,

Land der Brüderlichkeit,

Grandola braune Stadt.

Hinter jeder Ecke ein Freund,

In jedem Gesicht Gleichheit,

Grandola braune Stadt,

Land der Brüderlichkeit.

Land der Brüderlichkeit,

Grandola braune Stadt,

In jedem Gesicht Gleichheit,

In Dir regiert das Volk.

Im Schatten einer Korkeiche,

Die ihr Alter nicht mehr weiß,

Habe ich dir Treue geschworen,

Grandola, nach deinem Willen.

Grandola, nach deinem Willen,

Habe ich dir Treue geschworen,

Im Schatten einer Korkeiche,

Die ihr Alter nicht mehr weiß.

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi

eu:wikipedia

Traduzione letterale in lingua basca (Euskara) ripresa da eu.wikipedia con un po' di editing.

A literal translation into Basque (Euskara) reproduced from eu.wikipedia with some text editing.

José Alfonso, "Zeca" goitizenez, musikari eta abeslari portugaldarrak konposatu zuen abestia Krabelinen Iraultza baino urte batzuk lehenago. Sortzez, Grândola hiriko musika elkarte bati omenaldia egiteko sortu zuen abestia. Salazar diktadorearen erregimenak José Alfonsoren hainbat abesti zentsuratu zituen baina abesti hau disko batean agertu zen Frantzian, 1971. urtean, eta Krabelinen Iraultza baino egun batzuk lehenago, iraultzean parte hartuko zuten zenbait militarrek entzun zuten zuzenean.

1974ko martxoaren 29an, Grândola, Vila Morena Lisboako Coliseoan zuzeneko emanaldiaren azken abestia izan zen. Bertan zeuden, entzuten, MFAko zenbait militar ''Movimento das Forças Armadas'' eta ia hilabete beranduago, [apirilaren 25]ean, Krabelinen iraultzari hasiera emateko zeinu bezala aukeratu zuten. Lisboako Coliseoko emanaldian José Alfonsok ezin izan zituen bere abestietako batzuk plazaratu, Salazar erregimenaren zentsurak debekatuta baitzituen: Venham mais Cinco ("Hona bostekoa"), Menina dos Olhos Tristes ("Begi tristeetako neskatila"), A Morte Saiu à Rua ("Heriotza kalera irten zen") eta Gastão Era Perfeito ("Gastoi perfektua zen").

1974ko apirilaren 25ean, 0.20 orduan, Limite ("Muga") izeneko programan, Radio Renascença irrati katea Grândola, Vila Morena emititu zuen. Horixe zen bigarren eta azken zeinua Salazar diktadorearen erregimenari kolpea emateko. Kolpeak arrakasta izan zuen eta Portugal herrialdeak eta bere koloniek, handik aurrera askatasun handiagoa izan zuten.

Grândola, hiri beltzarana

Anaitasunaren lurraldea

Herria da gehien agintzen duena

Zugan, hiri hori.

Zugan, hiri hori,

Herria da gehien agintzen duena

Anaitasunaren lurralde hori

Grândola hiri beltzarana

Edozein txokotan, lagun bat

Aurpegi bakoitzean, berdintasuna

Grândola hiri beltzarana

Anaitasunaren lurraldea

Anaitasunaren lurraldea

Grândola hiri beltzarana

Aurpegi bakoitzean, berdintasuna

Herria da gehien agintzen duena

Artearen gerizpean

Adina ezagutzen ez nuen arteapean

Adiskide izango nuela zin egin nuen

Grândola, zure borondatea

Grândola, zure borondatea

Adiskide izango nuela zien egin nuen

Artearen gerizpean

Adina ezagutzen ez nuen arteapean.

Contributed by CCG/AWS Staff - 2012/8/1 - 18:36

Terra da fraternidade,

O povo é quem mais ordena

Dentro de ti, ó cidade.

Dentro de ti, ó cidade

O povo é quem mais ordena,

Terra da fraternidade,

Grândola, vila morena.

Oxalá, lá, o-oooh

Oxalá, lá, o-oooh

Oxalá, lá!

Em cada esquina um amigo,

Em cada rosto igualdade,

Grândola, vila morena

Terra da fraternidade!

Grândola, vila morena

Terra da fraternidade,

O povo é quem mais ordena

Dentro de ti, ó cidade.

À sombra duma azinheira

Que já não sabia a idade

Jurei ter por companheira

Grândola, a tua cidade.

Grândola a tua cidade

Jurei ter por companheira

À sombra duma azinheira

Que já não sabia a idade.

Herriak suntsituz diktadura [1]

eskuratu zuen boterea,

eta armak, zibilen eskuetan

klabelinetan bilakatu ziran.

Gorri kolorea hango ruetan!

Lore usaina hango ruetan!

Garaipena ere hango poboetan!

Ta meninoen aurpegietan!

Il popolo, sconfiggendo la dittatura prese il potere

e le armi, con l'aiuto dei civili

si trasformarono in garofani

Colore rosso per quelle strade!

Odore di fiori in quelle strade!

Anche la vittoria in quei paesi!

E nei visi dei bambini!

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2024/4/16 - 19:29

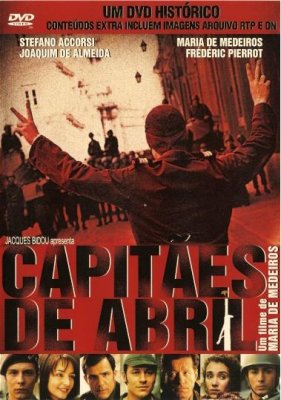

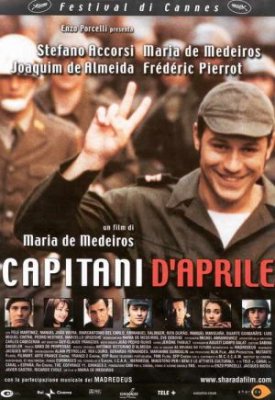

Da notare che la traduzione spagnola segue fedelmente il testo originale portoghese, mentre la versione cantata dai Betagarri, come detto, si prende qualche libertà. La traduzione spagnola della strofa in basco è quella sulla quale è stata basata la traduzione italiana presente nella sezione specifica. Nota finale: Non si ha notizia, almeno finora, di una vera e propria versione della canzone in spagnolo, cantata e/o recitata. Questo può essere senz’altro dovuto alla grande vicinanza (a livello scritto) tra il portoghese e lo spagnolo: non se ne deve mai esserne sentito il bisogno. Va detto anche che le versioni totalmente eteroglosse di Grândola sono poche: è quasi sempre stata cantata in portoghese. Qui sotto, un video tratto da una celebre scena del film Capitães de abril (Capitani d’Aprile) con una traduzione spagnola. [RV]

Grándola, villa morena

Tierra de fraternidad,

El pueblo es quien más ordena

Dentro de ti, oh ciudad.

Dentro de ti, oh ciudad,

El pueblo es quien más ordena,

Tierra de fraternidad,

Grándola, villa morena.

En cada esquina un amigo,

En cada rostro igualdad,

Grándola, villa morena

Tierra de fraternidad.

Grándola, villa morena

En cada rostro igualdad

El pueblo es quien más ordena

Dentro de ti, oh ciudad.

A la sombra de una encina

De la que no sabía su edad

Juré tener por compañera

Grándola, tu voluntad.

Grándola, tu voluntad

Juré tener por compañera,

A la sombra de una encina

De la que no sabía su edad.

y las armas, con la ayuda de los civiles

se convirtieron en claveles.

¡Color rojo en aquellas calles!

¡Olor a flores en aquellas calles!

¡También la victoria en aquellos pueblos!

¡Y en las caras de los niños!

Real Académia Galega

Come si sa (v. introduzione), la prima esecuzione in pubblico di Grândola, vila morena da parte di José Afonso e nella sua forma definitiva di canzone, avvenne il 10 maggio 1972 a Santiago de Compostela, in Galizia. In realtà, pare che José Afonso la avesse già cantata una prima volta, e proprio a Grândola, all’inaugurazione di una mostra sullo scrittore neorealista António Alves Redol; in tale occasione, José Afonso si esibì nel medesimo locale del 1964. Ma il pubblico era ridotto; a Santiago de Compostela, quindi, avvenne la prima esecuzione della canzone davanti a un vasto uditorio. José Afonso cantò Grândola al Burgo das Naçons di Santiago; il pubblico era composto principalmente da studenti sotto stretta sorveglianza da parte della polizia spagnola. José Afonso era stato invitato in Spagna per una tournée proprio da un musicista galiziano, Benedicto García Villar. L’accoglienza riservata a José Afonso e a Grândola, vila morena fu entusiastica: un segno evidente della forte opposizione a entrambe le dittature, che creò un saldo legame tra José Afonso e la Galizia mantenutosi fino alla morte dell’artista.

Un documento storico: L'intero recital di José Afonso al Burgo das Naçons di Santiago de Compostela, il 10 maggio 1972. "Grândola", cantata assieme a tutto il pubblico, è al minuto 37'56".

José Afonso, naturalmente, cantò la canzone in portoghese. Non ci sarebbe stato, e non c’è, alcun bisogno di una traduzione o versione: tra il portoghese e il galiziano funziona un po’ come tra l’italiano e il còrso: sono praticamente la stessa lingua, con lievi differenziazioni di carattere locale e storico, dovute alla separazione territoriale tra Portogallo e Galizia. Solo questo fa sì che le due lingue siano considerate e percepite come differenti (e, sia ben chiaro, i Galiziani ne hanno tutto il pieno diritto). La Real Académia Galega ne ha preparato una versione in galiziano che, per dichiarate intenzioni, vorrebbe far vedere quanto sono ora differenti il portoghese e il galiziano; beh, non per contraddire tale prestigiosa istituzione, ma dalla versione di Grândola appare ben poco. Ciononostante, ecco la versione (che abbiamo un po’ “editato” per farla meglio corrispondere alla struttura della canzone originale). [RV]

Grándola, vila morena

Terra da fraternidade

O pobo é quen mais ordena

Dentro de ti, ó cidade.

Dentro de ti, ó cidade

O pobo é quen mais ordena

Terra da fraternidade

Grándola, vila morena.

En cada esquina, un amigo

En cada rostro, igualdade

Grándola, vila morena

Terra da fraternidade.

Terra da fraternidade

Grándola, vila morena

En cada rostro, igualdade

O pobo é quen mais ordena.

Á sombra dunha aciñeira

Da que xá non sabia a idade

Xurei ter por compañeira

Grándola, a túa vontade.

Grándola, a tua vontade

Xurei ter por compañeira

Á sombra dunha aciñeira

Da que xá non sabia a idade.

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2024/4/24 - 09:12

MrMetaphysical (L. Trans.)

Grândola, vila moreta

Tèrra de fraternitat

Lo pòble es qual mai comanda

En ton sen, ó ciutat

En ton sen, ó ciutat

Lo pòble es qual mai comanda

Tèrra de fraternitat

Grândola, vila moreta

Dins cada cantonada un amic

Dins cada cara l'egalitat

Grândola, vila moreta

Tèrra de fraternitat

Tèrra de fraternitat

Grândola, vila moreta

Dins cada cara l'egalitat

Lo pòble es qual mai comanda

D'un euse a l'ombra

Que se sabiá pas mai l'edat

Jurèri aver per companha

Grândola, la teuna vontat

Grândola, la teuna vontat

Jurèri aver per companha

D'un euse a l'ombra

Que se sabiá pas mai l'edat.

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2024/4/19 - 20:56

Volkskoor Hei Pasoep!

La corale popolare Hei Pasoep! è una corale popolare fiamminga basata a Anversa, che ha preso nome da uno slogan del movimento sudafricano di resistenza anti-apartheid: Hei pasoep! significa “In guardia!” sia in afrikaans che in neerlandese. La versione è cantabile; l’anno di composizione non è specificato. [RV]

Grandola van de in Franse ballingschap levende dichter-zanger José Afonso werd door het fascistische bewind in Portugal verboden. Toen op 25 april 1974 Radio Renascença het lied om 00.30 u. uitzond, was dit het geheime signaal in code: "de staatsgreep gaat door". Een geweldloze staatsgreep van kritische jonge legerofficieren maakte een einde aan het autoritaire bewind van Salazar en zijn opvolger Caetano, een periode van ruim veertig jaar onderdrukking, kolonialisme, corporatisme en fascisme. Op straat deelde de enthousiaste bevolking anjers uit aan de soldaten. Daarom kreeg deze gebeurtenis de naam ‘Anjerrevolutie (Revolução dos Cravos)’.

Grandola van de in Franse ballingschap levende dichter-zanger José Afonso werd door het fascistische bewind in Portugal verboden. Toen op 25 april 1974 Radio Renascença het lied om 00.30 u. uitzond, was dit het geheime signaal in code: "de staatsgreep gaat door". Een geweldloze staatsgreep van kritische jonge legerofficieren maakte een einde aan het autoritaire bewind van Salazar en zijn opvolger Caetano, een periode van ruim veertig jaar onderdrukking, kolonialisme, corporatisme en fascisme. Op straat deelde de enthousiaste bevolking anjers uit aan de soldaten. Daarom kreeg deze gebeurtenis de naam ‘Anjerrevolutie (Revolução dos Cravos)’.Grandola, Moorse stad

Oase van broederlijkheid

Binnen uw muren, stad

Heeft het volk het voor het zeggen

Heeft het volk het voor het zeggen

Binnen uw muren, stad

Oase van broederlijkheid

Grandola, Moorse stad

Op elke hoek een vriend

In elk gelaat gelijkheid

Grandola, Moorse stad

Oase van broederlijkheid

Oase van broederlijkheid

Grandola, Moorse stad

In elk gelaat gelijkheid

Op elke hoek een vriend

In de schaduw van een kurkeik

Zo oud dat hij de jaren vergeten was

Zwoer ik dat jouw wil, Grandola

Mij verder zou begeleiden

Mij verder zou begeleiden

Zwoer ik dat jouw wil, Grandola

In de schaduw van een kurkeik

Zo oud dat hij de jaren vergeten was.

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2009/3/26 - 16:26

La traduzione russa proviene da Songs for Political Action (non è cantabile, è una semplice traduzione letterale; se ne dà ciononostante una trascrizione in caratteri latini).

"Грандола" - удивительно нежная, лиричная песня о городке в Португалии, где все люди - друзья, где все люди - братья. В ней нет даже намека на революцию, но она стала главной песней 25 апреля 1974 года - сигналом к началу "революции красных гвоздик" в Португалии. Автор "Грандолы" - Жозе Афонсо - Jose Afonso (1929-1985) написал ее в 1964 году, а записал на диск в 1971-м во Франции. Для португальцев она стала таким же символом революции, как для нас залп "Авроры". Но, конечно, революции португальской. И вот как это произошло.

"Грандола" - удивительно нежная, лиричная песня о городке в Португалии, где все люди - друзья, где все люди - братья. В ней нет даже намека на революцию, но она стала главной песней 25 апреля 1974 года - сигналом к началу "революции красных гвоздик" в Португалии. Автор "Грандолы" - Жозе Афонсо - Jose Afonso (1929-1985) написал ее в 1964 году, а записал на диск в 1971-м во Франции. Для португальцев она стала таким же символом революции, как для нас залп "Авроры". Но, конечно, революции португальской. И вот как это произошло.25 апреля 1974 года в 00 часов 20 минут 19-секундный фрагмент песни "Грандола" прозвучал по Радио Ринашенца в передаче, посвященной конкурсу "Евровидение". Это был сигнал к выступлению военных (преимущественно капитаны и лейтенанты армии и флота) против диктатуры. Через десять минут начались аресты сторонников диктатора Каэтану (преемника Салазара, который еще в 30-е годы установил в стране колониально-фашистский режим). К утру организаторы переворота (около 300 офицеров и несколько воинских частей) контролировали уже всю территорию страны. Хотя они и призвали жителей оставаться дома, тысячи португальцев высыпали на улицы, угощали солдат и матросов, свергнувших ненавистный диктаторский режим, сигаретами, едой и дарили им красные гвоздики.

Это как раз был сезон гвоздик - весна, которая стала весной свободы. Один из самых известных образов португальской революции - ребенок, вставляющий мирный цветок в дуло винтовки. "Грандола" вошла в историю как песня, ставшая сигналом для начала революции. А красная гвоздика в Португалии стала символом революции. К советской песне о "красной гвоздике - спутнице тревог" никакого отношения не имеет.

Грандола, Mавританское поселение, [1]

Земля братства

Главные люди, те, что решают все,

Все – твои жители , о город

Все – твои жители, о город -

Главные люди, те, что решают все,

Земля братства

Грандола, мавританское поселение.

На каждом углу - друг

В каждом лице - равный

Грандола, мавританское поселение,

Земля братства

Земля братства,

Грандола, мавританское поселение,

В каждом лице - равный

Главные люди, те, что определяют все.

В тени той азинейры ,

Что уже потеряла счет годам,

Я поклялся, что со мною будут

Избранные тобой, Грандола

Избранные тобой, Грандола,

Будут со мной, как обещано

В тени той азинейры,

Что уже потеряла счет годам.

Ziemlia bratstva

Głavnyje liudi, tie, čto riešajut vse,

Vsie – tvoj žitieli, o gorod

Vsie- tvoj žitieli, o gorod

Glavnye liudi, tie što riešajut vsie,

Ziemlia bratstva

Grandola, mavritanskoje posielienije.

Na každom ugłu – drug

V každom licie – ravnyj

Grandola, mavritanskoje posielienije,

Ziemlia bratstva,

Ziemlia bratstva,

Grandola, mavritanskoje posielienije,

V každom licie – ravnyj

Glavnyje liudi, tie, što riešajut vsie.

V tieni toj iaziniejry,

Što uže poteriała sčet godam,

Ja pokliałsia, što so mnogo budut

Izbrannyje toboj, Grandola

Izbrannyje toboj, Grandola,

Budut so mnoj, kak obiešćano

V tieni toj aziniejry,

Što uže poteriała sčet godam.

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2006/9/1 - 00:43

Iosif Chavkin (Иосиф Хавкин)

Грандола, поселок смуглый,

Братская земля родная,

Мы в ответе друг за друга,

Своим домом управляя.

Своим домом управляя,

Мы в ответе друг за друга.

Братская земля родная,

Грандола, поселок смуглый.

В каждом доме встретишь друга,

Равного себе узнаешь.

Грандола, поселок смуглый,

Братская земля родная.

Братская земля родная,

Грандола, поселок смуглый.

Равного себе узнаешь,

В каждом доме встретишь друга.

Я у дуба векового,

Что свои не помнит годы,

Грандола, тебе дал слово

Верным быть твоей свободе.

Верным быть твоей свободе

Я у дуба векового,

Что свои не помнит годы,

Грандола, тебе дал слово.

Grandola posiełok smugłyj,

Bratskaja ziemlia rodnaja,

My v otvietie drug za druga,

Svoim domom upravliaja.

Svoim domom upravliaja,

My v otvietie drug za druga.

Bratskaja ziemlia rodnaja,

Grandola posiełok smugłyj.

V každom domie vstrietiś druga,

Ravnovo siebie uznajeś.

Grandola posiełok smugłyj,

Bratskaja ziemlia rodnaja.

Bratskaja ziemlia rodnaja,

Grandola posiełok smugłyj.

Ravnovo siebie uznajeś,

V každom domie vstrietiś druga.

Ja u duba viekovovo,

Što svoj nie pomnit gody,

Grandola, tiebie dał slovo

Viernym byť tvojej svobodie.

Viernym byť tvojej svobodie

Ja u duba viekovovo,

Što svoj nie pomnit gody,

Grandola, tiebie dał slovo.

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2024/4/22 - 19:23

La versione polacca tradotta e cantata da Edyta Geppert fa parte di "Flower Power", una compilation pubblicata in Polonia in occasione del settantesimo anniversario della Seconda Guerra Mondiale (2009). L'album contiene famose canzoni di protesta da tutto il mondo, in nuovi arrangiamenti e con testi polacchi. Le canzoni di Dylan, Marley, The Animals e altri sono eseguite dalle star della musica polacca: Geppert, Kukiz, Maleńczuk, Staszewski, Markowski. I grandi artisti del mondo hanno sempre formato l'avanguardia degli oppositori della guerra e le loro canzoni sono diventate inni contro la guerra per molte generazioni. L'album include canzoni impegnate e di protesta proteste artistiche contro la guerra, la maggior parte delle quali sono state create negli Stati Uniti a cavallo tra gli anni '60 e '70. Queste canzoni sono state la voce della generazione dei "Figli dei fiori", che si ribellava alle norme sociali generalmente accettate. La compilation include anche canzoni di artisti europei, comprese canzoni di grandi bardi russi - Okudzhava e Vysotsky, nonché una canzone di Marek Grechuta.

Grandola Vila Morena

Kraj równości i braterstwa

O wolności tutaj śpiewa

Człowiek otwartego serca

Człowiek otwartego serca

O wolności tutaj śpiewa

Kraj równości i braterstwa

Grandola Vila Morena

Wokół nas przyjazna ziemia

Wyciągnięta czuła ręka

Grandola Vila Morena

Kraj równości i braterstwa

Kraj równości i braterstwa

Grandola Vila Morena

Wyciągnięta czuła ręka

Wokół nas przyjazna ziemia

W cieniu dębu stu letniego

Pochowałam przyjaciela

Będzie sławić imię jego

Grandola Vila Morena

Grandola Vila Morena

Będzie sławić imię jego

Pochowałam przyjaciela

W cieniu dębu stuletniego

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2018/6/22 - 18:34

Maja Gantar

Temna Grândola

Zemlja bratstva

Ljudstvo je tisto, ki ima besedo

V tebi, o mesto.

V tebi, o mesto

Ljudstvo je tisto, ki ima besedo

Zemlja bratstva

Temna Grândola.

Prijatelj na vsakem vogalu

Enakost na vsakem obrazu

Temna Grândola

Zemlja bratstva.

Zemlja bratstva

Temna Grândola

Enakost na vsakem vogalu

Ljudstvo je tisto, ki ima besedo.

V hrastovi senci

Katerga starosti že več ne vem

Prisegel sem, da bo moja spremljevalka

Volja tvoja, Grândola.

Volja tvoja, Grândola

Prisegel sem, da bo moja spremljevalka

V hrastovi senci

Katerega starosti že več ne vem.

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2024/4/24 - 10:30

La originalo, “Grândola Vila Morena” (alb. Cantigas do maio, 1971), estis unu la du kantoj uzataj kiel sekretaj signaloj en publika radio por alvoki kaj konfirmi la ekon de kontraŭdiktatura ŝtatrenverso kaj sensanga revolucio en Portugalio la jaron 1974.

La esperanta traduko estas apenaŭ kantata de portugalaj esperantistoj, malgraŭ la plua populareco de la originalo en tiu lando: Ne pro ideologiaj kaŭzoj sed memagnoskite pro du aŭ tri «neelteneblaj» mistradukoj (en ĝenerale sufiĉe bona tradukaĵo).

Ĝin kantis Gianfranco Molle.

Grandula, urbeto bruna

Vera hejmo de frataro

En vi regas vol’ komuna

En vi estas solidaro

En vi estas solidaro

en vi regas vol’ komuna

Vera hejmo de frataro

Grandula, urbeto bruna

En vi havas mi amikon

Temas pri la proletaro

Gradula, urbeto bruna

Vera hejmo de frataro

Grandula, urbeto bruna

Inter via proletaro

Plene regas vol’ komuna

En la ombro nun de kverko

Kiu aĝas sen komparo

Ĵuras sekvi mi ĝis ĉerko

Grandula, de vi leĝaron

Grandula, de vi leĝaron

Ĵuras sekvi mi ĝis ĉerko

En la ombro nun de kverko

Kiu aĝas sen komparo

Contributed by Nicola Ruggiero - 2009/3/7 - 21:06

Interpretata da Ana Ribeiro, 2022

Kantisto: Ana Ribeiro, 2022

(Lingva noto: anzino: (hispane encina, katalune alzina, portugale azinheira) daŭrfolia arbo precipe mediteranea (Quercus ilex; en NPIV nomata “verda kverko” aŭ “ilekskverko”; la nomo “anzino” aperis i.a. en Mondoj 2001, Koploj kaj filandroj 2009, Ombroj sur verda pejzaĝo 2012).

Grândola, urbeto bruna

Tero de fratecmesaĝo

Regas popolvol’ komuna

En vi, inda je omaĝo

En vi, inda je omaĝo

Regas popolvol’ komuna

Tero de fratecmesaĝo

Grândola, urbeto bruna

Jen amik’ ĉiuangule

Egaleco sur vizaĝoj

Grândola, urbeto bruna

Tero de fratecmesaĝo

Tero de fratecmesaĝo

Grândola, urbeto bruna

Egaleco sur vizaĝoj

Regas popolvol’ komuna

Sub la ombro de anzino

Forgesinta sian aĝon

Prenis mi por kompanino

Grândola vian kuraĝon

Grândola vian kuraĝon

Prenis mi por kompanino

Sub la ombro de anzino

Forgesinta sian aĝon

Contributed by Nicola Ruggiero - 2013/4/27 - 16:19

La versione, per quanto possa sembrare incredibile, in Polinesiano di Tahiti della canzone. È tratta dall'edizione tahitiana di Wikipedia; ed è anche un segno tangibile dell'ancora estrema fama di questa canzone.

Ò Grandola, te òire rava,

Fenua o te autaeaèraa

Te nunaa anaè tē mana

I roto ia òe, ô òire

I roto ia òe, ô òire

Te nunaa anaè tē mana

Fenua o te autaeaèraa

Ò Grandola, te òire rava,

Tē vai ra hōê hoa i te mau pae atoà

I te mau mata atoà, tē vai ra te àifāitoraa

Ò Grandola, te òire rava,

Fenua o te autaeaèraa

Fenua o te autaeaèraa

Ò Grandola, te òire rava,

I te mau mata atoà, tē vai ra te àifāitoraa

Te nunaa anaè tē mana

I te ata o te hōê tumu raau tahito .

Ua hōreo vau i te tāati ia òe

Ò Grândola, ta oè hinaaro

Ò Grândola, ta oè hinaaro

Ua hōreo vau i te tāati ia òe

I te ata o te hōê tumu raau tahito.

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2009/3/26 - 16:15

Riccardo Venturi, 11-6-2009

Μετέφρασε στα Ελληνικά ο Ρικάρντος Βεντούρης, 11 Ιούνιου 2009

Αν υπάρχει ένα τραγούδι που έκανε την ιστορία στην αληθινή σημασία του λόγου, τότε είναι Grândola vila morena. Απόλυτως, ένα από τα τραγούδια τα πιο διάσημα στην ιστορία και σίγουρα το πιο δίασημο στην ιστορία της Πορτογαλίας.

Πράγματι, η αναμετάδοση του τραγουδιού αυτού από τον Δζοζέ Αφόνσο σημείωσε την αρχή της Επαναστάσεως των Γαρυφάλων, η οποία έβαλε τέλος στη φασιστική δικτατορία στη Πορτογαλία, που διαρκούσε από 50 χρόνια. Το τραγούδι μετεδόθη από Λίμιτε, το νυχτερινό μουσικό πρόγραμμα του Rádio Renascença ("Ράδιο Αναγέννηση", ενός καθολικού ραδιοσταθμού), στη μεσανύχτα του 25 Απριλίου 1974. 'Hταν η αρχή της Επαναστάσεως, που την είπαν “των γαρυφάλων” από τα λουλούδια που μια πλανόδια πωλήτρια προσέφερε στους αντιφασίστες στρατιωτικοί το πρωί της επανάστασης, στην πλατεία ντο Κουμέρσιο.

'Ενα τραγούδι που οι στρατιωτικοί το διάλεγαν (μαζί μ'ένα ερωτικό τραγουδάκι από τον Πάουλο ντε Καρβάλιου, E depois do adeus 'Και μετά το αντίο', για σήμα προσυναγερμού· μ'αυτό, το τραγουδάκι εκείνο μπήκε επίσης στην ιστορία) γιάτι μιλάει γι'αδελφότητα, ειρήνη κι ομόνοια. Το τραγούδι έγινε σύμβολο και ύμνος των δημοκρατικών Ενοπλών Δυνάμεων, οι οποιες, έτσι για μια φορά, έκαναν πραγματικά το καλό του λαού τους (σταματώντας, συν τοις άλλοις, τους τρομερούς αποικιακούς πολέμους που αφαίμασσαν κυριολεκτικά τη χώρα).

'Οπως διηγείτο ο ίδιος Δζοζέ Αφόνσο, Grândola vila morena είχε συντεθεί σε τιμή της Sociedade Musical Fraternidade Operária Grandolense (Μουσική Εταιρία της Εργατικής Συνεταιρίας Γκράντολας· η Γκράντολα είναι μια πόλη στη νότια Πορτογαλία), ενός από τους πρώτους συνεταιρισμούς εργαζομένων που το καθεστώς τον κατέστειλε αυστηρά. Ο Δζοζέ Αφόνσο είχε δώσει ένα κοντσέρτο στη Γκράντολα στις 17 Μάιου 1964, κι ακριβώς με την ευκαιρία εκείνη ο τραγουδοποιός είχε γνωρίσει τον Κάρλος Παρέντες τον κιθαρίστα.

Αλλά τον Δζοζέ Αφόνσο τον είχε εντυπωσιάσει ο συνεταιρισμός πάνω απ'όλα· ένας “σκοτεινός χώρος, στερημένος απ'οποιανδήποτε υποδομή αλλά με μια βιβλιοθήκη και σαφείς επαναστατικούς σκοπούς και γενικευμένη πειθαρχία που την δέχτηκαν όλοι οι συνεταίροι. Αυτό φανέρωνε μεγάλη συνείδηση και πολιτική ωριμότητα.”

Αφότου εμφανίστηκε, το τραγούδι, που μιλούσε γι'έναν απαγορευμένο συνεταιρισμό, απαγορεύτηκε κι αυτό. Ο Δζοζέ Αφόνσο το είχε τραγουδήσει μερικές φορές δημοσία, και γι'αυτό έπρεπε να υποστεί μερικές συλλήψεις και ανακρίσεις από την τακτική αστυνομία κι απο τη PIDE, τη πολιτική αστυνομία.

'Oταν μετεδόθη ως σήμα αρχής για την κατάρρευση του φασιστικού καθεστώτος, Grândola ήταν ήδη συμβολικό τραγούδι.

Θυμάται ο ίδιος Δζοζέ Αφόνσο· “Δεν ήξερα ότι το τραγούδι το είχαν διαλέξει για σήμα της επανάστασης. Στις επομένες μέρες ούτε δεν το αναλογίστηκα. Το αναλογίστηκα όταν άρχισα να δω μάζες κόσμου που το τραγουδούσανε στις οδούς. 'Ηταν παράξενη αίσθηση, αλλά επἰσης πολύ ωραία.”

Στην πόλη Γκράντολας, ένα μεγάλο μνημείο φέρει τη παρτιτούρα και τους στίχους του τραγουδιού.

Γκρᾶντολα ἀραποπόλη

χώρα τῆς ἀδελφοσύνης

εἶν' ὁ λαός ὁ ἀφέντης

μέσ' ἀπὸ 'σένα, ὦ πόλη.

Μέσ' ἀπὸ 'σένα, ὦ πόλη

εἶν' ὁ λαός ὁ ἀφέντης,

χώρα τῆς ἀδελφοσύνης

Γκρᾶντολα ἀραποπόλη.

Σὲ κάθε γωνιὰ ἕνας φίλος,

ὁμόνοια σὲ κάθε πρόσωπο

Γκρᾶντολα ἀραποπόλη

χώρα τῆς ἀδελφοσύνης.

Χώρα τῆς ἀδελφοσύνης

Γκρᾶντολα ἀραποπόλη,

ὁμόνοια σὲ κάθε πρόσωπο

σὲ κάθε γωνιὰ ἕνας φίλος.

Στὴ σκιὰ μιᾶς βελανιδιάς

ποὺ δὲ ξέρεις τ'ἡλικίαν της

ὁ ὅρκος μου· νἆναι γιὰ μένα

σύντροφος τὸ θέλημά σου.

Σύντροφος τὸ θέλημά σου

ὁ ὅρκος μου, νἆναι γιὰ μένα,

στὴ σκιὰ μιᾶς βελανιδιάς

ποὺ δὲ ξέρεις τ'ἡλικίαν της.

Svensk version av Brita Papini e Maria Ahlström

Grândola är mina drömmars stad,

i broderskapets sköna trakter,

och där vänder vår historia blad

därav folket tagit makten.

Och där folket tagit makten

och där vänder vår historia blad

som i broderskapets trakter

i Grândola, i mina drömmars stad.

I varje stadsbo har jag en kamrat,

den sanna jämlikhetens vakter,

Grândola är mina drömmars stad

där i broderskapets trakter.

I broderskapets sköna trakter,

i Grândola, i mina drömmars stad

där vi är jämlikhetens vakter

och där vänder vår historia blad.

Sätter mig drut vid en havreträd

där jag får skugga ut av grönskan

jag svar Grândola min trohetsed:

uppfylla din frihets önskan.

Uppfylld ska din frihets önskan

svar Grândola din trohetsed

slå dig ned ut vid en havreträd

och får skugga ut av grönskan.

Grândola é a cidade dos meus sonhos

Grândola é a cidade dos meus sonhos

no belo país da irmandade,

e lá a nossa história vira a página

porque o povo tomou o poder.

Lá o povo tomou o poder

e lá a nossa história vira a página

como nos paises da irmandade

em Grândola, na cidade dos meus sonhos.

Em cada cidadão tenho um camarada,

guardiãos de verdadeira igualdade,

Grândola é a cidade dos meus sonhos

no belo país da irmandade.

No belo país da irmandade,

em Grândola, na cidade dos meus sonhos

onde a gente é guardiã da igualdade

e onde a nossa história vira a página.

Sento-me debaixo de uma azinheira

onde as folhas me dão sombra

e juro a Grândola a minha fidelidade:

satisfazer o teu desejo de liberdade.

O teu desejo de liberdade será satisfeito,

jure a Grândola a sua fidelidade,

sente-se debaixo de uma azinheira

e tome a sombra que a azinheira lhe dá.

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2009/7/10 - 14:11

Knud Møllenback

Nota. Avevo già qualificato questa cosa come "traduzione", quando mi sono accorto che, in realtà, è metrica e pienamente cantabile. Si tratta quindi di una vera e propria versione. [RV]

Grândola, du brune by

Her er broderskabets jord

Det er folket, som bestemmer

Her i byens midte

Her i byens midte

Det er folket, som bestemmer

Her er broderskabets jord

Grândola, du brune by

På hvert hjørne er en ven

I hvert ansigt findes lighed

Grândola, du brune by

Her er broderskabets jord

Her er broderskabets jord

Grândola, du brune by

I hvert ansigt findes lighed

Det er folket, som bestemmer

Her i skyggen af en sten-eg

Som ej mere ved sin alder

Sværged’ jeg at vær’ din følgesvend

Grândola, det er din vilje

Grândola, det er din vilje

Sværged’ jeg at vær’ din følgesvend

Her i skyggen af en sten-eg

Som ej mere ved sin alder.

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2024/4/23 - 18:45

--> ast:wikipedia

El cantar foi incluyíu nel álbum Cantigas do Maio, grabáu n'avientu de 1971, discu que cuenta colos arreglos y direción musical de José Mário Branco. "Grândola, Vila Morena" ye'l quintu tema del álbum, grabáu n'Herouville, Francia ente'l 11 d'ochobre y el 4 de payares de 1971.

Zeca Afonso estrenó'l cantar en Santiago de Compostela'l 10 de mayu de 1972.

El día 29 de marzu de 1974, Grândola, Vila Morena foi cantada na clausura d'un espectáculu nel Coliséu de Lisboa. Ente los asistentes taben militares del MFA, qu'escoyeríen el cantar como una de les señales pal entamu de la Revolución de los claveles. Curiosamente, pa esi espectáculu la censura del réxime facista prohibiera la interpretación de delles canciones de Zeca, ente elles: "Venham Mais Cinco", "Menina dos Olhos Tristes", "A Morte Saiu à Rua" y "Gastão Era Perfeito".

A la media nueche y venti minutos del día 25 d'abril de 1974, "Grândola, Vila Morena" foi tocada nel programa Limite de la Rádio Renascença. Yera la segunda señal que confirmaba la buena marcha de les operaciones de les fuerces organizaes pol MFA. La primer señal, sonara cerca d'hora y media anantes, a les 22 hores y 55 minutos del día 24 d'abril, foi "E depois do adeus", cantada por Paulo de Carvalho.

Grândola, villa prieta

Tierra de la fraternidá

El pueblu ye'l que más ordena

Dientro de ti, oh ciudá

Dientro de ti, oh ciudá

El pueblu ye'l que más ordena

Tierra de la fraternidá

Grândola, villa prieta

En cada esquina, un amigu

En cada rostru, igualdá

Grândola, villa prieta

Tierra de la fraternidá

Tierra de la fraternidá

Grândola, villa prieta

En cada rostru, igualdá

El pueblu ye'l que más ordena

A la solombra d'una encina

de la que nun sabía la edá

Xuré tener por compañera

Grândola, la to voluntá

Grândola, la to voluntá

Xuré tener por compañera

A la solombra d'una encina

de la que nun sabía la edá

Contributed by CCG/AWS Staff - 2012/8/1 - 18:30

Pentti Saaritsa - Agit Prop

Here's a link to Grandola, performed partly in Potuguese and partly in Finnish by Agit Prop

Terra da fraternidade

O povo é quem mais ordena

Dentro de ti, ó cidade

Dentro de ti, ó cidade

O povo é quem mais ordena

Terra da fraternidade

Grândola, vila morena.

Grandola maankolkka varjoinen

kehto taistelun ja veljeyden

On kansa käskyvallan ottanut

kaupunkinsa vapauttanut

Kaupunkinsa vapauttanut

siellä käskyvallan ottanut

Kehto taistelun ja veljeyden

Grandola maankolkka varjoinen

Alla rautatammen muinaisen

valan vannoin olla arvoinen

niiden jotka jatkaa taistellen

Grandola, oi kehto veljeyden

Grandola, oi kehto veljeyden

Valan vannoin jatkaa taistellen

alla rautatammen muinaisen

kehto taistelun ja veljeyden

Terra da fraternidade

O povo é quem mais ordena

Dentro de ti, ó cidade

Dentro de ti, ó cidade

O povo é quem mais ordena

Terra da fraternidade

Grândola, vila morena.

O povo é quem mais ordena

Terra da fraternidade

Grândola, vila morena.

Contributed by Juha Rämö - 2015/3/6 - 09:53

Grândola, vila morena,

terra de fraternitat,

és el poble qui governa

des del fons de la ciutat.

Des del fons de la ciutat,

és el poble qui governa,

terra de fraternitat,

Grândola, vila morena.

Un amic a cada casa,

igualtat entre nosaltres,

Grândola, vila morena,

terra de fraternitat.

Terra de fraternitat,

Grândola, vila morena,

igualtat entre nosaltres,

és el poble qui governa.

I a l’ombra d’una alzina,

que no sé quants anys tenia,

vaig jurar acompanyar-te

fins que no fossis ben lliure.

Fins que no fossis ben lliure

vaig jurar acompanyar-te.

Fou a l’ombra d’una alzina,

que no sé quants anys tenia.

Giorgio Pinna

Grandula, bidda mouriska

Terra de fraternidadi

Su populu est ki prus ordinat

Aintru de tui, o citadi.

Aintru de tui, o citadi

Su populu est ki prus ordinat

Terra de fraternidadi,

Grandula bidda mouriska.

In d'ogna skina un amigu

In d'ogna facci egualidadi

Grandula, bidda mouriska,

Terra de fraternidadi,

Terra de fraternidadi

Grandula bidda mouriska

In d'ogna facci egualidadi

Su populu est ki prus ordinat.

A s'umbra de unu ortigu

De ki no scidiad s'edadi

Jurai tenni a cumpangia

Grandula sa tua voluntadi,

Grandula sa tua voluntadi

Jurai tenni a cumpangia

A s'umbra de unu ortigu

De ki no scidiad s'edadi.

Stefania Secci Rosa [2020]

"Pubblicato sulla piattaforma YouTube da un collettivo di cantanti sarde coordinato da Stefania Secci Rosa, il brano “Grândola bidda morisca”, traduzione in lingua sarda della celeberrima canzone simbolo della rivoluzione dei garofani portoghese “Grândola Vila Morena” dell’autore e cantante lusitano Josè Afonso. Per celebrare l’Anniversario della Liberazione d’Italia, le cantanti Stefania Secci Rosa, Francesca Corrias, Claudia Aru, Alice Marras, Lulli Lostia e il trio delle Balentes composto da Stefania Liori, Pamela Lorico e Federica Putzolu hanno deciso di collaborare alla realizzazione della versione sarda della canzone simbolo della rivoluzione dei garofani in Portogallo risalente al 25 aprile del 1974. Il video e le illustrazioni sono a cura dell’illustratrice Marina Brunetti Marinetti. La traduzione del brano è stata curata da Stefania Secci Rosa con la verifica e i consigli sulla lingua sarda di Enrico Putzolu." - SH Magazine, 25 aprile 2020

“Ho deciso di adattare e tradurre in sardo il brano di Josè Afonso Grândola Vila Morena, che da oggi rivive anche nella versione intitolata Grândola bidda morisca per celebrare l’Anniversario della Liberazione d’Italia, coinvolgendo alcune tra le mie colleghe – spiega la cantante Stefania Secci Rosa – e con grande rammarico (a causa delle limitazioni che viviamo in questo periodo) non ho potuto estendere l’invito a tutte quelle che avevo previsto. Abbiamo registrato da casa e confezionato l’intero lavoro in soli due giorni, con l’aiuto dell’ingegnere del suono Emanuele Pusceddu. Per la realizzazione del video e delle illustrazioni ci siamo avvalse della collaborazione di Marina Brunetti Marinetti, illustratrice delicata e appassionata. Ad affiancarmi in questo progetto ci sono Francesca Corrias che apre il brano, seguita da Stefania Liori, e poi il trio delle Balentes composto da Pamela Lorico e Federica Putzolu, e poi Alice Marras, Lulli Lostia e Claudia Aru. Amo lavorare con le mie colleghe. Ogni volta succede qualcosa di speciale e questo è indubbiamente uno degli aspetti più affascinanti e gratificanti del mio lavoro. Questo brano vuole essere un bel regalo, nella speranza che venga ricantato in occasione dei prossimi anniversari della liberazione, come simbolo di fratellanza con il Portogallo, l’unico paese con cui condividiamo questa importantissima giornata.” - Stefania Secci Rosa

Questa versione sarda di Grândola vila morena risale a un 25 aprile di quattro anni fa, intesa per celebrare sia la festa della Liberazione d’Italia, sia la Rivoluzione dei Garofani portoghese. Si dà il caso che, il prossimo 25 aprile, sarà esattamente il 50° anniversario dell’insurrezione che liberò il Portogallo da una lunghissima dittatura fascista; qui in Italia, invece, i fascisti ce li abbiamo di nuovo al governo nazionale, e a parecchi governi regionali e locali. Poiché intendiamo festeggiare degnamente tale anniversario, abbiamo deciso di rifare quasi di sana pianta questa storica pagina del nostro sito e, nei limiti delle nostre possibilità, di ampliarla. A tale riguardo, cominciamo proprio con l’inserimento di questa versione sarda, opera di tutte donne (otto in tutto), proprio nel giorno in cui la Sardegna sembra cominciare a liberarsi dai fascisti, e con un’altra donna. Che tutto il resto d’Italia segua il suo esempio!

Ma…c’è un ma. Di questa (bellissima) versione sarda -che peraltro non è la prima si trova tutto in Rete (notizie, video, note autoriali…) tranne, naturalmente, il testo. Dico “naturalmente”, perché è sicuramente rivolta ad un uditorio che il sardo lo conosce e lo capisce già. Però il qui presente, che è toscano ma che ha una vaga infarinatura di sardo e, soprattutto, che è munito di tutta la panoplia sardista (dizionario del Martelli -toscano pure lui- e opere di Max Leopold Wagner -tedesco-, Eduardo Blasco Ferrer -catalano- e Massimo Pittau -nuorese-…), si è azzardato a tentare una trascrizione del testo all’ascolto. Fa dunque appello a qualche amico/a sardo/a perché riguardi un po’ il testo trascritto, sia dal punto di vista ortografico che prettamente linguistico. Grazie! Intanto, per questa pagina rifatta ci vediamo il 25 aprile prossimo. [Riccardo Venturi, 27 febbraio 2024]

Grândola bidda morisca,

Terra de fraternidadi,

Su populu gubernat [1]

Aintru de tui o citadi,

Aintru de tui o citadi,

Su populu gubernat,

Terra de fraternidadi,

Grândola bidda morisca.

In dogna cóntone un amicu,

In dogna cara equalitadi,

Grândola bidda morisca,

Terra de fraternidadi.

Terra de fraternidadi,

Grândola bidda morisca,

In dogna cara equalitadi,

Su populu gubernat.

A s’ombra de unu suergiu,

Che n’se nd’ isciri s’edadi,

Grândola sa mia cumpangia

Piad a sa tua voluntadi.

Piad a sa tua voluntadi,

Grândola sa mia cumpangia,

A s’ombra de unu suergiu,

Che n’se nd’isciri s’edadi.

Grândola bidda morisca,

Su populu gubernat,

Terra de fraternidadi,

Terra de fraternidadi,

Terra de fraternidadi,

Grândola bidda morisca.

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2024/2/27 - 22:44

Anonimo Toscano del XXI Secolo, 28-2-2024 09:42

Grandula, maure vice

In agro fraternitatis !

In te populus imperant

Et cives consociati.

Omnes cives consociati

Atque populus imperant

In agro fraternitatis,

Grandula, maure vice!

Et ubique patefaciunt

Sodales aequalitatem,

Grandula, Maure vice

In agro fraternitatis!

In agro fraternitatis,

Grandula, Maure vice,

Ubi cives consociati

Imperant aequalitate.

In frundosa umbra sedens

Vetustissimi suberis,

Voluntatem tuam iuravi

Fore meam in aeternitatem,

Fore meam in aeternitatem

Voluntatem tua iuravi

In frundosa umbra sedens

Vetustissimi suberis.

Grandola, kahverengi şehir

Kardeşliğin şehri

Birbirine göz kulak olan

İnsanların şehri, ah şehrim

Birbirine göz kulak olan

İnsanların şehri, ah şehrim

Kardeşliğin şehri

Grandola, kahverengi şehir

Her köşebaşında arkadaş bulabilirsin

Her suratta da eşitliği görebilirsin

Grandola, kahverengi şehrim

Kardeşliğin şehri

Kardeşliğin şehri

Grandola, kahverengi şehrim

Her suratta da eşitliği görebilirsin

Birbirine göz kulak olan insanların şehri

Yaşı bilinmeyen ulu

Meşelerin altında

Senin ile kan kardeşi olduk

Grandola, senin iraden ile

Grandola, senin iraden ile

Kan kardeşi olduk

Yaşı bilinmeyen ulu

Meşelerin altında

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2024/4/22 - 20:06

Eli Pinto (L. Trans.)

גְּרַנְדֹּלָה היא עיר קטנה [1]

במחוז סטובל שבפורטוגל. האנשים שם ידידותיים

וכך היא נקראת ארץ האחווה והאנשים שם

חופשים לעשות כרצונם ואדונים לעצמם

ושם בתוך העיר

האנשים הם שנותנים את הפקודות [2]

ארץ האחווה גְּרַנְדֹּלָה

עיר קטנה ושְׁחוּמָה

בכל פינה יש חבר

בכל מקום יש שוויון מלא

גְּרַנְדֹּלָה עיר קטנה ושְׁחוּמָה

ארץ האחווה

ארץ האחווה

גְּרַנְדֹּלָה עיר קטנה ושְׁחוּמָה

בכל מקום יש שוויון מלא

ואף אחד לא אומר לשני מה לעשות

בצילו של עץ אלון עתיק

שכבר לא זוכר בן כמה הוא

נשבעתי שאהיה לצדך

עד שתהיה חופשי לעשות כרצונך

עד שתגשים את החלומות

נשבעתי להיות לצידך

מתחת לצילו של עץ האלון העתיק

שכבר אף אחד לא זוכר בן כמה הוא

Contributed by Riccardo Venturi - 2024/4/23 - 08:27

Riccardo Venturi - 2006/5/24 - 00:01

scusami tu, non avevo letto con attenzione l'introduzione...

Oltretutto la canzone di de Carvalho, che io ho definito "struggente" (ad essere sincero non l'avevo ancora ascoltata...) è davvero una canzonetta, come dici giustamente. Insipida, certo, ma mica a tutte le canzonette capita di essere Storia!

Alessandro - 2006/5/24 - 09:21

Saluti!

Riccardo Venturi - 2006/5/24 - 10:50

Riccardo Venturi - 2007/5/3 - 21:21

Morena, in the Portuguese Language, means Brunet or Sun-Tanned not Moor! Even if the its origin is a Castilian word that originaly meant Moor (but no more even in modern Spanish). Nobody in Portugal associates Morena with the Moors. I'm changing the translation. The Ogre 14:46, 19 September 2006 (UTC)

Lorenzo - 2007/5/4 - 09:29

1) Que ou aquele que possui cor trigueira;

2) (Env.) Relativo aos mouros

3) (Prov.) Mistura de limalha de ferro e pó de carvão que se deposita nas forjas

(Do cast. "moreno", de "moro", "mouro").

Dicionário da língua Portuguesa, por J. Almeida Costa e A. Sampaio e Melo

6a Edição, Porto Editora, Lisboa, 1990, pag. 1132

Aggiungiamo anche il fatto che il traduttore russo, del tutto autonomo sia da noi che da Wikipedia, ha correttamente inteso "morena" e lo ha tradotto addirittura con "mavritanskoe selo", vale a dire nientemeno che "città mauritana". Il che è del tutto giusto dal punto di vista storico.

Ad ogni modo il wikipedista cambi quello che vuole su Wikipedia inglese; qui resta così com'è. [RV]

Riccardo Venturi - 2007/5/4 - 12:12

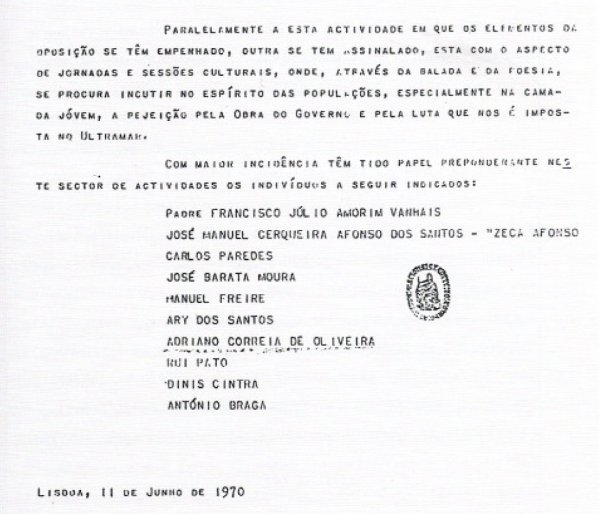

Il seguente documento originale (riprodotto dal documento .pdf scaricabile da Canto de Intervenção) è un'eccezionale testimonianza della censura del regime salazarista applicata al mondo della canzone portoghese. Datato 11 giugno 1970 e rinvenuto negli archivi del ministero degli interni, riunisce in un'unica censura tutti i più grandi nomi della canzone d'autore portoghese.

"Parallelamente a questa attività nella quale sono impegnati gli elementi dell'opposizione, ne è stata segnalata un'altra, questa sotto l'aspetto di giornate e sessioni culturali, dove, mediante ballate e poesie, si cerca di incutere nello spirito della popolazione, e in particolare della fascia giovanile, il rifiuto dell'Opera del Governo e per la guerra che ci è imposta nell'Oltremare.

Con maggiore incidenza, hanno avuto un ruolo preponderante in questo settore di attività i seguenti individui:

Padre Francisco Júlio Amorim Vanhais (in realtà: Francisco Fanhais)

José Manuel Cerqueira Afonso Dos Santos - « Zeca » Afonso

Carlos Paredes

José Barata Moura

Manuel Freire

Adriano Correia De Oliveira

Rui Pato

Dinis Cintra

António Braga"

CCG/AWS Staff - 2009/3/26 - 01:59

"Na Rádio Renascença a gravação do alinhamento, que viria a ser o sinal para o desencadear das operações, foi feita na tarde do dia 24 de Abril, por Leite de Vasconcelos, para ser emitida no Programa «Limite», que era realizado em directo, mas algumas partes eram previamente gravadas. Era numa dessas gravações que estava a «senha» - a primeira quadra da música «Grândola, Vila Morena», de Zeca Afonso, senha escolhida pelo MFA.

Grândola vila morena

Terra da fraternidade

O povo é quem mais ordena

Dentro de ti ó cidade

Esta segunda senha confirmou a primeira. A partir daqui as operações militares estão em marcha e são irreversíveis

"A Rádio Renascença, la registrazione della traccia che sarebbe stata il segnale per l'inizio delle operazioni fu effettuata la sera del 24 aprile da Leite de Vasconcelos, per essere poi trasmessa nel programma 'Limite', che andava in onda in diretta; ma alcune parti erano state registrate precedentemente. Era esattamente in una di queste preregistrazioni che era contenuto il 'segnale', la prima strofa della canzone 'Grândola Vila Morena' di Zeca Afonso, segnale scelto dal MFA.

Grândola vila morena

Terra da fraternidade

O povo é quem mais ordena

Dentro de ti ó cidade

Tale secondo segnale confermò il primo. A partire da quel momento le operazioni militari si misero in moto e furono irreversibili."

Riccardo Venturi - 2009/3/26 - 13:09

"Ocupação de pontos estratégicos considerados fundamentais ( RTP, Emissora Nacional, Rádio Clube Português, Aeroporto de Lisboa, Quartel General, Estado Maior do Exército, Ministério do Exército, Banco de Portugal e Marconi). O Rádio Clube Português é transformado no posto de comando do «Movimento das Forças Armadas», por este motivo a emissora fica conhecida como a "Emissora da Liberdade". Aos Microfones do Rádio Clube Português, Joaquim Furtado lê o primeiro Comunicado do MFA:

«Aqui posto de comando do Movimento das Forças Armadas.

As Forças Armadas portuguesas apelam para todos os habitantes da cidade de Lisboa no sentido de recolherem a suas casas, nas quais se devem conservar com a máxima calma.

Esperando sinceramente que a gravidade da hora que vivemos não seja tristemente assinalada por qualquer acidente pessoal, para o que apelamos ao bom senso do comando das forças militares no sentido de serem evitados quaisquer confrontos com as Forças Armadas.

Tal confronto, além de desnecessário, só poderá conduzir a sérios prejuízos individuais, que enlutariam e criariam divisões entre portugueses, o que há que evitar a todo o custo.

Não obstante a expressa preocupação de não fazer correr a mínima gota de sangue de qualquer português, apelamos para o espírito cívico e profissional da classe médica, esperando a sua ocorrência aos hospitais, a fim de prestar a sua eventual colaboração, o que se deseja sinceramente desnecessária.»

“Occupazione dei punti strategici considerati fondamentali (RTP -Rádio Televisão Portuguesa-, Radio Nazionale, Rádio Clube Português, Aeroporto di Lisbona, Quartier Generale, Stato Maggiore dell'Esercito, Ministero della Difesa, Banca del Portogallo e Marconi). Il Rádio Clube Português è trasformato in posto di comando del “Movimento delle Forze Armate”, e per questo l'emittente è da allora nota come “Radio Libertà”. Dai microfoni del Rádio Clube Português, Joaquim Furtado legge il primo comunicato del MFA:

”Qui il posto di comando del Movimento delle Forze Armate.

Le Forze Armate portoghesi fanno appello a tutti gli abitanti della città di Lisbona affinché si raccolgano nelle proprie case, nelle quali dovranno conservare la massima calma.

Nella sincera speranza che la gravità dell'ora che viviamo non sia tristemente segnata da alcun incidente personale, facciamo appello al buon senso al comando delle forze militari affinché sia evitato qualsiasi scontro con le Forze Armate.

Tale scontro, oltre che inutile, potrà solo condurre a seri danni personali, che farebbero sorgere confronti armati e creerebbero divisioni tra portoghesi; questo deve essere evitato ad ogni costo.

Nononstante l'esplicita intenzione di non fare scorrere la benché minima goccia di sangue di alcun portoghese, facciamo appello allo spirito civico e professionale della classe medica, pregandola di recarsi agli ospedali per prestare la propria eventuale collaborazione, che si desidera sinceramente non necessaria.”

Riccardo Venturi - 2009/3/26 - 13:24

Todo o filme Capitães de Abril sobre o dia do 25 de Abril de 1974, a Revolução dos Cravos e a queda da ditadura fascista em Portugal.

Capitães de Abril é um filme realizado por Maria de Medeiros, em 2000. A sua estreia teve bastante sucesso e recebeu varios prémios nacionais e internacionais. A história é baseada num golpe de estado militar, que ocorreu em Portugal, a 25 de Abril de 1974. Na noite do 24 para o 25 de Abril de 1974, a rádio emite uma canção proibida : Grândola Vila Morena. Poderia apenas ter sido a insubmissão de um jornalista rebelde mas, na realidade, é um dos sinais programados do golpe de estado militar que vai transformar completamente o país, sujeito à ditadura do Estado Novo durante várias décadas, e o destino das colónias portuguesas em África e em Timor Leste. Ao som da voz do poeta e cantor José Afonso, as tropas insurgidas tomam os quartéis. Cerca das três horas da madrugada, marcham para Lisboa. Pouco depois do triste acontecimento militar no Chile, a Revolução dos Cravos distingue-se pelo carácter aventureiro, mas também pacífico e lírico do seu decorrer. Estas 24 horas de revolução são vividas por três personagens principais : dois capitães e uma mulher que é professora de literatura e jornalista. Capitães de Abril é a primeira longa metragem de Maria de Medeiros como realizadora. Ela presta deste modo homenagem a esses jovens soldados que salvaram a sua pátria desse demasiado tempo obscuro. - pt:wikipedia

(il film non è più disponibile su youtube)

CCG/AWS Staff - 2009/6/27 - 01:11

RM - 2021/8/15 - 19:43

Lorenzo - 2021/9/8 - 00:16

Primo semestre 2013: come altri stati, il Portogallo si vede imporre dall’ “Unione Europea” una rigorosa politica di austerità. Durante le manifestazioni, si leggono spesso cartelli come questo: QUE SE LIXE A TROIKA! O POVO É QUEM MAIS ORDENA (“Che la Troika vada a farsi fottere! E’ il popolo che più comanda”). In una situazione di difficoltà e di lotta, ritorna Grândola vila morena.

Nel febbraio del medesimo anno, l’allora primo ministro portoghese, Pedro Passos Coelho, leader del principale partito di destra del paese che si chiama, però, “Partito Socialdemocratico”, prende la parola in parlamento per illustrare le severe misure richieste dalla UE. Viene interrotto immediatamente da un discreto numero di deputati delle sinistre, che cantano in coro una certa canzone:

Il primo ministro, in diretta TV, sorride nervoso mentre risuonano i versi di Grândola vila morena e la speaker del Parlamento tenta di ridargli la parola. Persino il ministro di destra deve riconoscere l’abilità dei protestatari e commenta: “Non si potrebbe essere interrotti in un modo migliore”. Il fatto si ripete anche in altre sedi, e nelle piazze.

Da questo momento, la lingua portoghese si arricchisce di un neologismo: il verbo grandolar, dal significato: “impedire a un politico di parlare cantando Grândola vila morena”. O ministro X foi grandolado em Santarém ecc., “il ministro X è stato ‘grandolato’ a Santarém”.

L'Anonimo Toscano del XXI Secolo - 2024/4/19 - 22:15

To the Unpolish Uncontributor

Ti ringraziamo non-molto per il tuo non-contributo a questa non-pagina con il non-video della non-versione non-polacca di non-Edyta Geppert; ma, come puoi non-vedere, c'era non-già.

We thank you unvery unmuch for your noncontribution to this unpage with the nonvideo of the Unpolish unversion by Unedyta Ungeppert; but, as you can unsee, it was unalready in the unpage.

Non-Riccardo Nonventuri - 2024/4/29 - 20:40

Sono andato in Portogallo nell estate del 1975 . In Angola a gennaio erano partiti gli accordi per l'indipendenza che sarebbe avvenuta in Novembre. Nell estate del 75 migliaia di portoghesi lasciarono l'Angola e rientrarono in Portogallo che per ospitarli requisi gli alberghi.

Ci trovammo così in viaggio senza sapere dove dormire e i nostri letti furono i giardini pubblici i vagoni dei treni. In Alentejo di alberghi non ce ne erano proprio ovviamente la dittatura non promuoveva il turismo Dormimmo anche ai bordi di un cimitero dopo una serata di musica con Amalia Rodriguez. Ma che belle erano Alcobaca ,Batalia, Tomar le loro cattedrali i monasteri.

Conoscemmo José che era scappato a Parigi per non fare il servizio militare che dura a 6 anni ed adesso era rientrato nel suo paese. Finalmente trovammo un letto per dormire. Fu davvero un viaggio indimenticabile in un paese povero ma liberato

Paolo Rizzi - 2024/5/4 - 10:28

Cosa curiosa... un regime fascista venne abbattuto da un colpo di stato militare coordinato attraverso la radio cattolica.. E questo ci dimostra due cose che quel regime era così degradato così ormai avulso dalla realtà che a deporlo sono gli stessi militari...

Assai inprobabile che si potesse parlare di militari di sinistra in un paese come il Portogallo dopo 50 anni di dittatura.

Erano arrivati al punto di cui anche i militari non ne potevano più di questi dittatura e si erano resi conto che il Portogallo doveva tornare nell'Europa nel novero dei paesi democratici.

Marcello - 2024/8/10 - 02:52

I lavoratori GKN lottano per il proprio lavoro e per la dignità dal 9 luglio 2021 con l'appoggio di molte persone serie e di molte realtà della politica fiorentina ed europea.

Io non sto con Oriana - 2025/4/6 - 10:59

Lorenzo Masetti - 2025/4/6 - 11:05

Nel 2008, Pino Masi pubblica presso le edizioni “Il Campano” (nella “biblioteca tascabile” ‘Repubblicapisana’) il volumetto ‘Quarant’anni cantati – Canzoni e vita dell’ultimo cantastorie’, consistente in tutti in testi delle canzoni da lui scritte e/o cantate a partire dal 1966 fino, appunto, al 2008. I testi delle canzoni sono inframezzati da una sorta di autobiografia pinomasiana, scritta nel suo particolarissimo stile, dalla quale estrapoliamo (pag. 87) un breve ed assai curioso passo che riguarda José Afonso e la canzone di questa pagina:

“Per il resto il ‘75 fu anno di cose nuove e buone. Ispirazione al bene, argomenti da approfondire, sogni, viaggi tra le due sponde, amicizie, Fatima, Fawzia, Yani...e a sorpresa Lionello, il regista Massobrio amico di Adriano [Sofri, ndr], mi preleva da Selinunte e di corsa si va a Roma, sulla sua MG: ‘...c’è stata la rivoluzione pacifica, Salazar è caduto ed ora...” Un aereo militare portoghese cala con me su Lisbona e, a sorpresa, mi riceve Carlalberto, che mi porta a cantare, tutta la notte, al Pavillao dello Sport, di fronte a un popolo...di oltre quindicimila elementi umani gaudenti e osannanti, in duo con Seca Fonso, il grande cantastorie portoghese...la cui canzone Grandula Villa Morena, messa in onda, a sorpresa, da un’amica alla radio nazionale, ha dato il via, come segnale, al sollevamento pacifico di tutte le caserme. Grande Seca, ora da anni scomparso! Ecco: un filo di poesia, che adesso vedo, lega mio nonno...a Nenni, a Pasolini, a Seca Fonso e a me!”

Riccardo Venturi - 2025/4/7 - 00:29

La Rivoluzione dei Garofani del 25 aprile 1974 ha avuto, come è noto e come risulta da questa pagina, tutta una sua “colonna sonora” fin dall’inizio. Una colonna sonora assolutamente unica e sorprendente: dalla canzonetta sentimentale dell’Eurofestival (E depois do adeus) alle canzoni più strettamente politiche (Grândola, Os vampiros) ed alla marcia militare statunitense (Life on the Ocean Waves, v. Introduzione). Quel che è meno noto, e che fino ad oggi consideravo quasi come una leggenda metropolitana, è che lo storico primo comunicato del Movimento delle Forze Armate, letto alle ore 4.26 del 25 aprile 1974 dal giornalista Joaquim Furtado e trasmesso dallo RCP (Radio Clube Português), fosse stato introdotto anch’esso da un brano musicale. Del Primo Comunicato esistono tutte le registrazioni possibili e immaginabili (v. Introduzione), ma nessuna prima di adesso era stata reperita con il preambolo musicale. Finalmente, oggi, ne è stata reperita una dalla quale risulta che il Comunicato che metteva fine a quasi cinquant’anni di dittatura in Portogallo era introdotto dal Ballo del Qua Qua (in portoghese: Baile dos Passarinhos, o Passarinhos a bailar):

E così, in un’ipotetica raccolta di “Canti e brani musicali della Rivoluzione dei Garofani” (o “del 25 aprile 1974”) dovrebbe, e a buon diritto, essere inserito anche il Ballo del Qua Qua (composto, lo ricordiamo, nel 1957 dal musicista svizzero Werner Thomas, titolo originale: Der Ententanz). Tutto potevo aspettarmi nella vita, ma che il Ballo del Qua Qua fosse una CCG, no. Meraviglie di quella oramai lontana e unica rivoluzione!

N.B. Se si ascolta tutto il documento sonoro si potrà notare che, dopo il Ballo del Qua Qua e il Primo Comunicato del Movimento das Forças Armadas, viene mandato in onda l’inno nazionale portoghese (A Portuguesa, 1895). Ciò significa che, in quella fatidica nottata, il Ballo del Qua Qua ebbe la preminenza anche sull’inno nazionale!

Riccardo Venturi - 2025/10/6 - 19:51

Una briachìssima esecuzione di Grândola vila morena la sera del 14 novembre 2025 alla Federazione Anarchica Livornese. Il secondo da sinistra è André Ferreira, del Coro da Achada di Lisbona. Quello più alto in fondo è invece il misterioso Anonimo Toscano del XXI Secolo. Si riconoscono anche alcuni membri del Coro Stazione Rossa. Che lo spirito di Zeca Afonso ci perdoni!

Riccardo Venturi - 2025/11/15 - 10:14

Note for non-Italian users: Sorry, though the interface of this website is translated into English, most commentaries and biographies are in Italian and/or in other languages like French, German, Spanish, Russian etc.

[1964; 1971]

Letra / Testo / Lyrics / Paroles / Sanat: José Afonso, 1964

Música / Musica / Music / Musique / Sävel: José Afonso, 1971

Album / Albumi: Cantigas do Maio, 1971

QUICK INDEX OF VERSIONS AVAILABLE (In 23 languages up to now)

Italiano 1 (Riccardo Venturi 2003/04) – Italiano 2 (Quarup, versione equiritmica) - Francese 1 (Riccardo Venturi 2003) – Francese 2 (Jadis, L. Trans.) - Inglese – Tedesco 1 (Franz Josef Degenhardt 1975) - Tedesco 2 – Basco - Versione bilingue portoghese e basca (Euskara) (Betagarri 1997) – Spagnolo – Galiziano (Real Académia Galega) - Occitano - Neerlandese (Volkskoor Hei Pasoep!) – Russo 1 – Russo 2 (Iosif Chavkin) - Polacco (Edyta Geppert 2009) - Sloveno (Maja Gantar) - Esperanto 1 (Gianfranco Molle 1979) – Esperanto 2 (Jorge Camacho) - Tahitiano - Greco (Riccardo Venturi 2009) - Svedese (Brita Papini - Maria Ahlström 1981) - Danese (Knud Møllenback) - Asturiano - Finlandese (Pentti Saaritsa - Agit Prop 1974) - Catalano (Marina Rossell 2015) - Sardo 1 (Giorgio Pinna) - Sardo 2 (Stefania Secci Rosa 2023) - Latino (Anonimo Toscano del XXI Secolo 2024) - Turco - Ebraico (Eli Pinto)

Italian 1 (Riccardo Venturi 2003/04) – Italian 2 (Quarup, equirhythmic version) - French 1 (Riccardo Venturi 2003) – French 2 (Jadis, L. Trans.) - English – German 1 (Franz Josef Degenhardt 1975) – German 2 – Basque - Bilingual version, Portuguese and Basque (Betagarri 1997) – Spanish – Galician (Real Académia Galega) - Occitan - Dutch (Volkskoor Hei Pasoep!) – Russian 1 – Russian 2 (Iosif Chavkin) - Polish (Edyta Geppert 2009) - Slovene (Maja Gantar) - Esperanto 1 (Gianfranco Molle 1979) - Esperanto 2 (Jorge Camacho) - Tahitian - Greek (Riccardo Venturi 2009) - Swedish (Brita Papini - Maria Ahlström 1981) - Danish (Knud Møllenback) - Asturian - Finnish (Pentti Saaritsa - Agit Prop 1974) - Catalan (Marina Rossell 2015) - Sardinian 1 (Giorgio Pinna) - Sardinian 2 (Stefania Secci Rosa 2023) - Latin (Anonimo Toscano del XXI Secolo 2024) - Turkish - Hebrew (Eli Pinto)

Una pagina sottoposta ad un totale rifacimento, che ha occupato quasi un anno di lavoro, in modo da corrispondere al 25 Aprile. Il 25 Aprile del Portogallo e della Rivoluzione dei Garofani, col suo Cinquantesimo anniversario, e il 25 Aprile italiano, Festa della Liberazione dal nazifascismo, di cui il prossimo anno cadrà l’80° anniversario. Da questo momento, 22 aprile 2024, questa diventa una "Pagina Speciale" a tutti gli effetti, e nel senso più vasto del termine. "Grândola vila morena" è una canzone che ha fatto la Storia, ed anche una Rivoluzione. E, tanto per smentire almeno una volta un altro consolidato luogo comune, ha fatto finire anche delle guerre, quelle coloniali del Portogallo.

La pagina, come detto, è stata totalmente rifatta ed ampliata. Non soltanto con nuove traduzioni e versioni (rimettendo anche in ordine quelle già presenti: è una pagina antichissima di questo sito, una “CCG Primitiva”), ma anche e soprattutto redigendo un’introduzione molto ampia e dettagliata. Ancor più ampio e dettagliato è il saggio storico di João Madeira, Ricardo Andrade e Hugo Castro, “Grândola, Vila morena: uses and meanings of a song throughout the years” (pubblicato nel 2024 su Zapruder), che abbiamo pubblicato integralmente a mo’ di introduzione in inglese, sottoponendolo a un corposo editing. Si tratta di una vera e propria monografia sulla canzone, la cui lettura è imprescindibile.

di Riccardo Venturi.

Se mai esiste una canzone che ha fatto la storia nel senso più completo del termine, questa è Grândola vila morena. In assoluto, una delle canzoni più famose della storia e sicuramente la più famosa di tutta quella del Portogallo.

Fu infatti proprio la trasmissione di questa canzone di José Afonso (fino ad allora assolutamente proibita a tutte le emittenti pubbliche e private del Portogallo) dalle onde di "Limite", il programma musicale quotidiano notturno di "Rádio Renascença", un'emittente cattolica di proprietà diretta della Curia portoghese, che diede il segnale d'inizio alla Revolução dos Cravos, la "Rivoluzione dei Garofani" (così chiamata dai fiori che una venditrice ambulante, Celeste Martins Caeiro, si mise a offrire ai militari di sinistra la mattina del sollevamento, in Praça do Comércio) che mise fine alla dittatura fascista portoghese, che durava da oltre quarant'anni. La trasmissione della canzone avvenne esattamente alle ore 00,20 del 25 aprile 1974.

Un documento storico: La registrazione originale della trasmissione di Grândola vila morena dalle onde di Rádio Renascença (“Radio Rinascita” in portoghese). Sono le ore 00,20 del 25 aprile 1974; la canzone viene brevemente introdotta dall'annunciatore radiofonico che recita i primi versi della canzone.

La canzone di José Afonso rappresentò in realtà il “Secondo segnale” (2a Senha) del pronunciamento militare; il “Primo segnale” (1a Senha), trasmesso durante il programma musicale Limite dalla stessa Rádio Renascença alle ore 23,00 del 24 aprile, rappresentava il segnale convenzionale di preallarme. Si trattava di una canzonetta d'amore di Paulo de Carvalho, E depois do adeus, scelta anch'essa dai militari forse con un pizzico di ironia, poiché era il classico lamento dell'innamorato mandato al gas dalla fidanzata. Con questo, anche la canzonetta di Paulo de Carvalho entrò nella Storia, e dalla porta principale. Ma fu la trasmissione di Grândola (canzone la cui trasmissione era sì severamente proibita, ma che era in libera vendita sia come singolo, sia come facente parte dell'album Cantigas do Maio) che segnò il vero inizio delle operazioni militari e, in pratica, dell'intera Rivoluzione). Una canzone che parla di fraternità, di pace e di uguaglianza fu presa a simbolo da delle forze armate che, una volta tanto, fecero veramente il bene del loro popolo (interrompendo, tra le altre cose, le sanguinose e anacronistiche guerre coloniali che stavano letteralmente dissanguando il Portogallo).

È proprio tra la fine degli anni '60 e l'inizio degli anni '70 che i giovani artisti portoghesi alzano la voce. Per oltre quarant'anni, a partire dal 1926, il paese si trovava governato dalla dittatura fascista di António de Oliveira Salazar, che aveva dissipato il potenziale economico e umano del Portogallo in una serie di guerre coloniali atte a ribadire la “grandezza” dell'impero portoghese, mentre il paese si trovava in una situazione interna disastrosa che non lasciava altra via d'uscita che l'emigrazione. L'espressione aperta di opinioni critiche, ad esempio in libri di qualsiasi genere e in giornali, non era permessa dalla censura e dall'onnipresente polizia politica, la PIDE. Una delle poche forme per esprimere lo scontento e le speranze di cambiamento era senz'altro la canzone; ma anche questa era sottoposta a pesantissime censure e a divieti, e gli artisti prelevati e portati in galera non furono pochi. Tra questi, anche e soprattutto José Afonso. Ad un certo punto, si arrivò a proibire di menzionare il suo stesso nome nei giornali e in ogni tipo di pubblicazione; per questo motivo, lo si scriveva al contrario (“Esoj Osnofa”) per evadere la censura.

Il 29 marzo 1974, meno di un mese prima della Rivoluzione dei Garofani, presso il Coliseu dos Recreios (un auditorium polivalente situato nella Rua das Portas de Santo Antão a Lisbona) si tenne il “Primo Incontro della Canzone Portoghese” (I Encontro da Canção Portuguesa), Si trattava in realtà sì di un incontro musicale, ma nel titolo di chiama non si poteva certo dire che si trattava della canzone di protesta e di denuncia contro la dittatura dell'Estado Novo (talmente “novo” che aveva già oltre quarant'anni ed era già abbondantemente imputridito). La cosa non era ovviamente sfuggita alle autorità, che si erano affrettate a proibirlo. Ciononostante, la sala era già stracolma fino all'inverosimile: si calcola che vi fossero ammassate settemila persone. Dopo un lungo ritardo (poiché già recarvisi costituiva un atto di protesta contro la dittatura), e con ulteriori e lunghissime file di persone all'esterno, le autorità decisero di far tenere il concerto. La Polícia de Segurança Pública (PSP) e la Guarda Nacional Republicana (GNR) erano già pronte a sgomberare la sala e le strade adiacenti con la forza, ma non ricevettero alcun ordine: la quantità di persone era talmente smisurata, che neppure le autorità fasciste se la sentirono di provocare un disastro di proporzioni inimmaginabili. Fu quindi deciso di dare inizio allo spettacolo, ma con una censura ferrea: tra tagli, censure totali e divieti, trenta canzoni furono eliminate. Diversi artisti pensarono che sarebbe stato meglio non tenere lo spettacolo in quelle condizioni; si decisero poi a tenerlo comunque, per rispetto verso il pubblico. Pur con una pessima qualità fonica, si cominciò con qualche canzone “permessa”; il pubblico non si scaldò fino all'esibizione di António Macedo, la cui canzone Canta, canta amigo era nota negli ambienti dell'opposizione, e che fu intonata in coro da una larga parte delle persone presenti. Si esibirono poi il chitarrista Carlos Paredes (che José Afonso aveva conosciuto proprio a Grândola nel 1964) e Maria do Amparo; al momento dell'esibizione di José Carlos Ary dos Santos (che, nel 1969, aveva aderito al Partito Comunista Portoghese) partirono cori e slogan antifascisti. Fu poi il turno di artisti come Manuel Freire (noto per aver cantato anche dei testi di José Saramago, come Ouvindo Beethoven), Adriano Correia de Oliveira, José Barata Mouro e Fernando Tordo. Sta per esibirsi, per ultimo, José Afonso. Tra il pubblico si sente canticchiare, senza parole, il motivo della sua canzone più proibita, Os vampiros; a questo punto “parte la bambola”, e la polizia non riesce più a contenere il pubblico; la PIDE comincia a “identificare” artisti, tecnici e persone presenti tra il pubblico, mentre si sentono urla. “Fascisti! Fascisti!”. Sul palco, Manuel Freire dice ironicamente di “essersi purtroppo scordato le parole di alcune canzoni mentre arrivava in teatro”, suscitando applausi e risate fragorose; José Jorge Letria fa una finta aria desolata e dice: “Mi piacerebbe cantare, se potessi....”, e giù di nuovo applausi e risate. José Afonso chiude il concerto interpretando una delle poche canzoni che erano state permesse: Grândola vila morena, che viene accompagnata nel canto dalle migliaia di persone presenti. La scena viene descritta come “impressionante” da chi c'era.

29 marzo 1974: Il "I Incontro della Canzone Portoghese" al Coliseu dos Recreios con immagini e registrazioni originali.

Al momento della consegna dei premi (l' “Incontro” era stato organizzato come un vero e proprio festival), Adelino Gomes, che aveva ricevuto uno dei premi, dichiara:

“Questo riconoscimento non premia il lavoro individuale di una persona, ma tutto ciò che alcuni di noi cerchiamo di dire e che ci hanno proibito di dire. Inoltre, è un omaggio a ciò che molti di voi avrebbero desiderato sentire, e che non vi è stato permesso di ascoltare.”

Al che José Afonso torna sul palco e ripete Grândola vila morena di nuovo tra le urla di "Fascisti! Fascisti". Nel frattempo, la macchina del colpo di stato militare antifascista è già ampiamente in moto; Grândola è già diventata una canzone-simbolo, e probabilmente proprio la reazione del pubblico all'esibizione di José Afonso al Coliseu dos Recreios la fa scegliere come segnale per l'avvio delle operazioni (oltre al fatto che Rádio Renascença aveva il permesso di trasmetterla). Senonché, Carlos Albino, un membro di coordinamento del Movimento das Forças Armadas, si accorge all'ultimo momento che, nonostante la avesse già trasmessa, Rádio Renascença non possiede una copia della canzone. Alle ore 11 del mattino del 24 aprile 1974, si reca allora, senza informare nessuno, alla libreria “Opinião” in Praça do Alvalade, dove acquista, per essere sicuro, una copia sia dell'album Cantigas do Maio, sia del 45 giri del 1973 con Grândola vila morena. Alle ore 14, nella sua edizione del pomeriggio, il quotidiano República inserisce una breve notizia intitolata “LIMITE”, del seguente tenore: