In labor's glorious history was many a union maid

Who stood up to the bosses, so staunch and unafraid.

Molly Jackson, Mother Jones fought for a brighter way.

But let's sing of Fannie Sellins, and remember her today.

All over Pennsylvania Fannie spread the Union word.

In the coalfields and the company towns her voice of hope was heard:

"United we will bargain, but divided we will beg"

Fannie Sellins spread the dreams of the UMWA.

A widow with four children, toiling eighty hours a week

Found time to fight injustice and bring power to the meek.

She lived with tireless energy, no duty would she shirk.

Though murderers cut short her life, we carry on her work.

In the company slums of Ducktown in the summer of nineteen,

An unarmed striking miner was gunned down by deputies.

When Fannie cried out, "Spare his life!" They shot her down as well.

And hundreds watched in horror as this fearless woman fell.

Now the ones who gave the orders faced no charge of any sort.

And the men who pulled the triggers were acquitted by the court.

But when companies own the courthouse, justice fails for you and me.

So let's work like Fannie Sellins now for true equality.

A widow with four children, toiling eighty hours a week

Found time to fight injustice and bring power to the meek.

She lived with tireless energy, no duty would she shirk.

And though murderers cut short her life, we carry on her work.

Though murderers cut short her life, we carry on her work.

Who stood up to the bosses, so staunch and unafraid.

Molly Jackson, Mother Jones fought for a brighter way.

But let's sing of Fannie Sellins, and remember her today.

All over Pennsylvania Fannie spread the Union word.

In the coalfields and the company towns her voice of hope was heard:

"United we will bargain, but divided we will beg"

Fannie Sellins spread the dreams of the UMWA.

A widow with four children, toiling eighty hours a week

Found time to fight injustice and bring power to the meek.

She lived with tireless energy, no duty would she shirk.

Though murderers cut short her life, we carry on her work.

In the company slums of Ducktown in the summer of nineteen,

An unarmed striking miner was gunned down by deputies.

When Fannie cried out, "Spare his life!" They shot her down as well.

And hundreds watched in horror as this fearless woman fell.

Now the ones who gave the orders faced no charge of any sort.

And the men who pulled the triggers were acquitted by the court.

But when companies own the courthouse, justice fails for you and me.

So let's work like Fannie Sellins now for true equality.

A widow with four children, toiling eighty hours a week

Found time to fight injustice and bring power to the meek.

She lived with tireless energy, no duty would she shirk.

And though murderers cut short her life, we carry on her work.

Though murderers cut short her life, we carry on her work.

Contributed by giorgio - 2010/1/6 - 08:24

×

![]()

Note for non-Italian users: Sorry, though the interface of this website is translated into English, most commentaries and biographies are in Italian and/or in other languages like French, German, Spanish, Russian etc.

Lyrics & Music by Anne Feeney

Album: Union Maid

Fanny was born Fanny Mooney in New Orleans in 1872 and married garment worker Charles Sellins in St. Louis. Widowed with death of husband, Fanny took a job in a St. Louis garment factory to support her four children. She later moved to Chicago and became involved in the union movement. In 1911 when a garment factory locked out 400 women workers, Fanny became a negotiator in a struggle that lasted two years. She helped to organize the United Garment Workers of America and came to national attention with her fiery oratory at meetings across the country collecting money for strikers and calling for boycotts of anti-union companies.

In 1913, the United Miner Workers of America (UMWA) took notice of Fanny and brought her to Pittsburgh. They assigned her to aid and organize mine workers in West Virginia. She moved to the anti-union area of Colliers, West Virginia, to support families driven out of their homes by the Pennsylvania and West Virginia Coal Company. Fanny wrote of that her work there was to distribute "clothing and food to starving women and babies, to assist poverty stricken mothers and bring children into the world, and to minister to the sick and close the eyes of the dying."

A coal-operator friendly judge banned all union organizing activity in Colliers and forbade memberships in unions. Fanny defied the anti-union injunction and spoke out against the judge’s efforts to stifle free speech and the right to association. At a miner’s rally Fanny said:

"I am free and I have a right to walk or talk any place in this country as long as I obey the law. I have done nothing wrong. The only wrong they can say I've done is to take shoes to the little children in Colliers. And when I think of their bare little feet, blue with the cruel blasts of winter, it makes me determined that if it be wrong to put shoes upon those little feet, then I will continue to do wrong as long as I have hands and feet to crawl to Colliers."

Fanny was charged with "inciting to riot" and served six months in prison for defending constitutional freedoms. In response to a mine workers petition campaign, President Woodrow Wilson pardoned Fanny in December of 1916.

Fanny then moved to New Kensington in Allegheny-Kiski valley to recruit miners into the UMWA union. The Allegheny Valley was called the “Black Valley” because of the violent repression of mine owners to union organizers. An able energetic idealistic speaker Fanny persuaded thousands of miners and steel workers in the region to join the union. She visited the miner’s homes, talked to their wives, and took care of their sick. She raised the awareness of the immigrant miners about their rights and inspired them to demand better working conditions. The coal operators of the Black Valley feared and hated Fanny Sellins and threatened to “get her”.

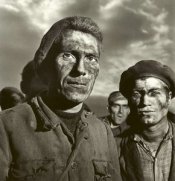

In 1919 UMWA president Phil Murray assigned Fanny to work with miners on strike from the Allegheny Coal and Coke Company in New Kensington. On August 26, 1919 a dozen drunken sheriff’s deputies along company guards rushed picketing strikers outside a mine in Brackenridge, Pa. The deputies and guards clubbed and shot at the strikers wounding five. Sellins and a group of women and children watched in horror as guards fatally beat and shot striking miner Joseph Starzelski. Fanny ran to the aid the dying miner. The guards turned on Fanny, chased her into a miner’s back yard, clubbed her crushing her skull, shot her in the back, flipped her over and shot her in the face in cold blooded murder. In one account of the story the guards then danced before the crowd of mining families wearing her hat and mocking her. They then threw her body into the back of a truck. The coroners report describes two bullets to the head, one from behind and the other from the front, as well as a depressed fracture running from her left eye to above her right ear.

Fannie died at age 49 a grandmother whose only son was killed in World War I fighting for democracy. On August 29, 1919 in New Kensington a crowd estimated at 10,000 marched in the funeral procession for Joseph Starzelski and Fanny Sellins. They were buried at the Union Cemetery in Arnold, Pa. where the UMWA erected a memorial in their honor. The memorial’s inscription reads: "In memory of Fannie Sellins and Joe Starzelecki, killed by the enemies of organized labor”. In 1989, Sellins' grave was designated a Pennsylvania state historic landmark and an historic marker was built which reads: "An organizer for the United Mine Workers, Fannie Sellins, was brutally gunned down in Brakenridge on the eve of a nationwide steel strike on August 26, 1919."

The American labor press called her death an assignation. Mother Jones called her death a murder at the UMWA convention 8 days after Fannie’s death. Phil Murray of the UMWA wrote to President Wilson and the governor demanding an investigation. Many persons witnessed the murder and the guilty were named in newspapers. Two sheriff deputies were eventually arrested. But witnesses were intimidated. In 1923 an Allegheny County corner’s jury ruled that Fanny’s death was justifiable and commended Sheriff Haddock for protecting the property of Allegheny Coal and Coke against alien agitators who instill anarchy and bolshevism in the minds of uneducated UnAmericans. The two deputies accused of Fanny’s murder were acquitted.

The frightening picture of Fannie’s battered face hung in union halls around Pittsburgh. The forces of economic repression silenced Fannie’s voice, but her drive for free speech and the fight to unionize lived on.

“She fought with tireless energy, no duty would she shirk / though murderers cut short her life – we carry on her work." – Ann Feeney