I had said I wasn't going to write no more poems like this

I had confessed to myself all along, tracer of life, poetry trends

That awareness, consciousness, poems that screamed of pain and the origins of pain and death had blanketed my tablets

And therefore, my friends, brothers, sisters, in-laws, outlaws, and besides

They already knew

But brother Torres, common ancient bloodline brother Torres is dead

I had said I wasn't going to write no more poems like this

I had said I wasn't going to write no more words down about people kicking us when we're down, about racist dogs that attack us and drive us down, drag us down and beat us down but the dogs are in the street

The dogs are alive and the terror in our hearts has scarcely diminished

It has scarcely brought us the comfort we suspected

The recognition of our terror and the screaming release of that recognition

has not removed the certainty of that knowledge, how could it

The dogs rabid foaming with the energy of their brutish ignorance

Stride the city streets like robot gunslingers

And spread death as night lamps flash crude reflections from gun buts and police shields

I had said I wasn't going to write no more poems like this

But the battlefield has oozed away from the stilted debates of semantics

beyond the questionable flexibility of primal screaming

The reality of our city, jungle streets and their kastapos

Has become an attack on home, life, family and philosophy, total

It is beyond the question of the advantages of didactic niggerism

The mother fucking dogs are in the street

In Houston maybe someone said Mexicans were the new niggers

In LA maybe someone said Chicanos were the new niggers

In Frisco maybe someone said Orientals were the new niggers

Maybe in Philadelphia and North Carolina they decided they didn't need no new niggers

I had said I wasn't going to write no more poems like this

But dogs are in the streets; It's a turn around world where things are all too quickly turned around

It was turned around so that right looked wrong; it was turned around so that up looked down

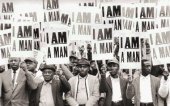

It was turned around so that those who marched in the streets with bibles and signs of peace became enemies of the state and risk to national security

So that those who questioned the operations of those in authority on the principles of justice, liberty, and equality became the vanguard of a communist attack

It became so you couldn't call a spade a mother-fucking spade

Brother Torres is dead, the Wilmington ten are still incarcerated

Ed Davis, Ronald Regan, James Hunt, and Frank Rizzo are still alive

And the dogs are in the mother-fucking street

I had said I wasn't going to write no more poems like this

I made a mistake

I had confessed to myself all along, tracer of life, poetry trends

That awareness, consciousness, poems that screamed of pain and the origins of pain and death had blanketed my tablets

And therefore, my friends, brothers, sisters, in-laws, outlaws, and besides

They already knew

But brother Torres, common ancient bloodline brother Torres is dead

I had said I wasn't going to write no more poems like this

I had said I wasn't going to write no more words down about people kicking us when we're down, about racist dogs that attack us and drive us down, drag us down and beat us down but the dogs are in the street

The dogs are alive and the terror in our hearts has scarcely diminished

It has scarcely brought us the comfort we suspected

The recognition of our terror and the screaming release of that recognition

has not removed the certainty of that knowledge, how could it

The dogs rabid foaming with the energy of their brutish ignorance

Stride the city streets like robot gunslingers

And spread death as night lamps flash crude reflections from gun buts and police shields

I had said I wasn't going to write no more poems like this

But the battlefield has oozed away from the stilted debates of semantics

beyond the questionable flexibility of primal screaming

The reality of our city, jungle streets and their kastapos

Has become an attack on home, life, family and philosophy, total

It is beyond the question of the advantages of didactic niggerism

The mother fucking dogs are in the street

In Houston maybe someone said Mexicans were the new niggers

In LA maybe someone said Chicanos were the new niggers

In Frisco maybe someone said Orientals were the new niggers

Maybe in Philadelphia and North Carolina they decided they didn't need no new niggers

I had said I wasn't going to write no more poems like this

But dogs are in the streets; It's a turn around world where things are all too quickly turned around

It was turned around so that right looked wrong; it was turned around so that up looked down

It was turned around so that those who marched in the streets with bibles and signs of peace became enemies of the state and risk to national security

So that those who questioned the operations of those in authority on the principles of justice, liberty, and equality became the vanguard of a communist attack

It became so you couldn't call a spade a mother-fucking spade

Brother Torres is dead, the Wilmington ten are still incarcerated

Ed Davis, Ronald Regan, James Hunt, and Frank Rizzo are still alive

And the dogs are in the mother-fucking street

I had said I wasn't going to write no more poems like this

I made a mistake

inviata da Bartleby - 22/12/2011 - 12:06

×

![]()

Dall’album “The Mind of Gil Scott-Heron”.

Dopo H2OGaTe Blues e We Beg Your Pardon (Pardon Our Analysis), lo sguardo di Scott-Heron si sposta dall’“universale” del Watergate al “particolare” di una vicenda che scosse l’America nel 1977 e 1978.

José “Joe” Campos Torres era un ventitreenne di origine messicana, veterano della guerra in Vietnam.

Nel maggio del 1977 fu arrestato a Houston per aver fatto casino in un bar. Sei poliziotti bianchi lo pestarono selvaggiamente e quando si accorsero di averlo ridotto in fin di vita, anziché portarlo in ospedale, lo affogarono nel Buffalo Bayou, un corso d’acqua che attraversa la città texana.

Il corpo martoriato di Joe Campos Torres fu ritrovato due giorni dopo.

Erano i tempi in cui i militanti del Ku Kux Klan si facevano fotografare seduti sulle auto della polizia di Houston e i loro reclutatori venivano ospitati nei locali della polizia di Houston

Ed erano i tempi in cui il capo della polizia Herman Short non aveva vergogna a dichiarare pubblicamente: “Non vedo contraddizione tra essere del KKK ed essere al tempo stesso un ufficiale della polizia di Houston”.

Ed erano i tempi in cui certe dichiarazioni non suscitavano nessun orrore perché nella maggior parte dei locali di Houston erano affissi cartelli che recitavano “No dogs or Mexicans allowed”.

I poliziotti Terry Denson, Steven Orlando e Joseph Janish, tre dei poliziotti assassini, furono processati ma un anno più tardi la condanna fu soltanto per “condotta negligente”, sicchè ebbero l’affidamento in prova, si fecero qualche mese, pagarono $1 (un dollaro) di sanzione e se ne andarono liberi…

Questa vergognosa sentenza, che coincise con il primo anniversario dell’assassinio di Joe Campos Torres, scatenò dei gravissimi disordini che si concentrarono al Moody Park di Houston e che videro protagonisti la comunità ispanica e diverse organizzazioni impegnate contro la brutalità delle forze di polizia. Gli scontri e le devastazioni durarono due giorni, con centinaia di feriti e decine di arresti.

“Fratello Torres è morto, i dieci di Wilmington sono ancora in carcere [si riferisce a dieci attivisti per i diritti civili imprigionati dal 1971 dopo gravi scontri razziali nel North Carolina, ndr], Ed Davis, Ronald Reagan, James Hunt e Frank Rizzo sono ancora vivi [si riferisce a uomini politici e poliziotti buttatisi in politica, ndr] e i cani [si riferisce ai poliziotti, ndr] sono ancora nelle maledette strade. Ed io avevo detto che non avrei più scritto poesia come questa. Ma mi sono sbagliato.”