Kurt Vonnegut: Slaughterhouse-Five, or the Children's Crusade: A Duty-Dance With Death

LA CCG NUMERO 15000 / AWS NUMBER 15000| Originale | Suomennos Juhani Jaskari 1970 |

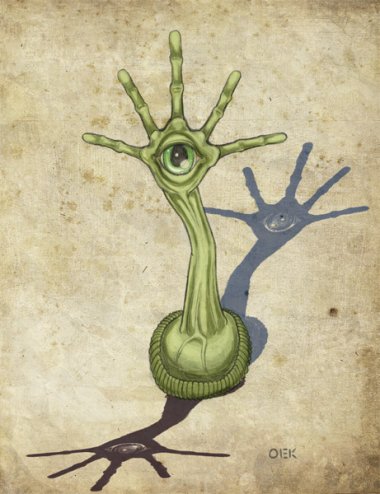

| KURT VONNEGUT: SLAUGHTERHOUSE-FIVE, OR THE CHILDREN'S CRUSADE: A DUTY-DANCE WITH DEATH All this happened, more or less. The war parts, anyway, are pretty much true. One guy I knew really was shot in Dresden for taking a teapot that wasn't his. Another guy I knew really did threaten to have his personal enemies killed by hired gunmen after the war. And so on. I've changed all the names. I really did go back to Dresden with Guggenheim money (God love it) in 1967. It looked a lot like Dayton, Ohio, more open spaces than Dayton has. There must be tons of human bone meal in the ground. I went back there with an old war buddy, Bernard V. O'Hare, and we made friends with a taxi driver, who took us to the slaughterhouse where we had been locked up at night as prisoner of war. His name was Gerhard Müller. He told us that he was a prisoner of the Americans for a while. We asked him how it was to live under Communism, and he said that it was terrible at first, because everybody had to work so hard, and because there wasn't much shelter or food or clothing. But things were much better now. He had a pleasant little apartment, and his daughter was getting an excellent education. His mother was incinerated in the Dresden fire-storm. So it goes. He sent O'Hare a postcard at Christmastime, and here is what it said: 'I wish you and your family also as to your friend Merry Christmas and a happy New Year and I hope that we'll meet again in a world of peace and freedom in the taxi cab if the accident will.' I like that very much: 'If the accident will.' I would hate to tell you what this lousy little book cost me in money and anxiety and time. When I got home from the Second World War twenty-three years ago, I thought it would be easy for me to write about the destruction of Dresden, since all I would have to do would be to report what I had seen. And I thought, too, that it would be a masterpiece or at least make me a lot of money, since the subject was so big. But not many words about Dresden came from my mind then-not enough of them to make a book, anyway. And not many words come now, either, when I have become an old fart with his memories and his Pall Malls, with his sons full grown. I think of how useless the Dresden -part of my memory has been, and yet how tempting Dresden has been to write about, and I am reminded of the famous limerick: There was a young man from Stamboul, Who soliloquized thus to his tool, 'You took all my wealth And you ruined my health, And now you won't pee, you old fool’ And I'm reminded, too, of the song that goes My name is Yon Yonson, I work in Wisconsin, I work in a lumbermill there. The people I meet when I walk down the street, They say, 'What's your name? And I say, ‘My name is Yon Yonson, I work in Wisconsin... And so on to infinity. Over the years, people I've met have often asked me what I'm working on, and I've usually replied that the main thing was a book about Dresden. I said that to Harrison Starr, the movie-maker, one time, and he raised his eyebrows and inquired, 'Is it an anti-war book?' 'Yes,' I said. 'I guess.' 'You know what I say to people when I hear they're writing anti-war books?' 'No. What do you say, Harrison Starr?' 'I say, "Why don't you write an anti-glacier book instead?"' What he meant, of course, was that there would always be wars, that they were as easy to stop as glaciers. I believe that too. And, even if wars didn't keep coming like glaciers, there would still be plain old death. * A couple of weeks after I telephoned my old war buddy, Bernard V. O'Hare, I really did go to see him. That must have been in 1964 or so-whatever the last year was for the New York World's Fair. Eheu, fugaces labuntur anni. My name is Yon Yonson. There was a young man from Stamboul. [...] And the sun went down, and we had supper in an Italian place, and then I knocked on the front door of the beautiful stone house of Bernard V. O'Hare. I was carrying a bottle of Irish whiskey like a dinner bell. I met his nice wife, Mary, to whom I dedicate this book. I dedicate it to Gerhard Müller, the Dresden taxi driver, too. Mary O'Hare is a trained nurse, which is a lovely thing for a woman to be. [...] That was about it for memories, and Mary was still making noise. She finally came out in the kitchen again for another Coke. She took another tray of ice cubes from the refrigerator, banged it in the sink, even though there was already plenty of ice out. Then she turned to me, let me see how angry she was, and that the anger was for me. She had been talking to herself, so what she said was a fragment of a much larger conversation. "You were just babies then!' she said. 'What?" I said. 'You were just babies in the war-like the ones upstairs! ' I nodded that this was true. We had been foolish virgins in the war, right at the end of childhood. 'But you're not going to write it that way, are you.' This wasn't a question. It was an accusation. 'I-I don't know,' I said. 'Well, I know,' she said. 'You'll pretend you were men instead of babies, and you'll be played in the movies by Frank Sinatra and John Wayne or some of those other glamorous, war-loving, dirty old men. And war will look just wonderful, so we'll have a lot more of them. And they'll be fought by babies like the babies upstairs.' So then I understood. It was war that made her so angry. She didn't want her babies or anybody else's babies killed in wars. And she thought wars were partly encouraged by books and movies. So I held up my right hand and I made her a promise 'Mary,' I said, 'I don't think this book is ever going to be finished. I must have written five thousand pages by now, and thrown them all away. If I ever do finish it, though, I give you my word of honor: there won't be a part for Frank Sinatra or John Wayne. 'I tell you what,' I said, 'I'll call it The Children's Crusade.' She was my friend after that. ***  Billy looked at the clock on the gas stove. He had an hour to kill before the saucer came. He went into the living room, swinging the bottle like a dinner bell, turned on the television. He came slightly unstuck in time, saw the late movie backwards, then forwards again. It was a movie about American bombers in the Second World War and the gallant men who flew them. Seen backwards by Billy, the story went like this: American planes, full of holes and wounded men and corpses took off backwards from an airfield in England. Over France a few German fighter planes flew at them backwards, sucked bullets and shell fragments from some of the planes and crewmen. They did the same for wrecked American bombers on the ground, and those planes flew up backwards to join the formation. The formation flew backwards over a German city that was in flames. The bombers opened their bomb bay doors, exerted a miraculous magnetism which shrunk the fires gathered them into cylindrical steel containers, and lifted the containers into the bellies of the planes. The containers were stored neatly in racks. The Germans below had miraculous devices of their own, which were long steel tubes. They used them to suck more fragments from the crewmen and planes. But there were still a few wounded Americans, though, and some of the bombers were in bad repair. Over France, though, German fighters came up again, made everything and everybody as good as new. When the bombers got back to their base, the steel cylinders were taken from the racks and shipped back to the United States of America, where factories were operating night and day, dismantling the cylinders, separating the dangerous contents into minerals. Touchingly, it was mainly women who did this work. The minerals were then shipped to specialists in remote areas. It was their business to put them into the ground., to hide them cleverly, so they would never hurt anybody ever again. The American fliers turned in their uniforms, became high school kids. And Hitler turned into a baby, Billy Pilgrim supposed. That wasn't in the movie. Billy was extrapolating. Everybody turned into a baby, and all humanity, without exception, conspired biologically to produce two perfect people named Adam and Eve, he supposed. ***  Another month went by without incident, and then Billy wrote a letter to the Ilium News Leader, which the paper published. It described the creatures from Tralfamadore. The letter said that they were two feet high, and green, and shaped like plumber's friends. Their suction cups were on the ground, and their shafts, which were extremely flexible, usually pointed to the sky. At the top of each shaft was a little hand with a green eye in its palm. The creatures were friendly, and they could see in four dimensions. They pitied Earthlings for being able to see only three. *** Billy expected the Tralfamadorians to be baffled and alarmed by all the wars and other forms of murder on Earth. He expected them to fear that the Earthling combination of ferocity and spectacular weaponry might eventually destroy part or maybe all of the innocent Universe. Science fiction had led him to expect that. But the subject of war never came up until Billy brought it up himself. Somebody in the zoo crowd asked him through the lecturer what the most valuable thing he had learned on Tralfamadore was so far, and Billy replied, 'How the inhabitants of a whole planet can live in peace I As you know, I am from a planet that has been engaged in senseless slaughter since the beginning of time. I myself have seen the bodies of schoolgirls who were boiled alive in a water tower by my own countrymen, who were proud of fighting pure evil at the time. ' This was true. Billy saw the boiled bodies in Dresden. 'And I have lit my way in a prison at night with candles from the fat of human beings who were butchered by the brothers and fathers of those school girls who were boiled. Earthlings must be the terrors of the Universe! If other planets aren't now in danger from Earth, they soon will be. So tell me the secret so I can take it back to Earth and save us all: How can a planet live at peace?' Billy felt that he had spoken soaringly. He was baffled when he saw the Tralfamadorians close their little hands on their eyes. He knew from past experience what this meant: He was being stupid. 'Would-would you mind telling me,' he said to the guide, much deflated, 'what was so stupid about that?' 'We know how the Universe ends,' said the guide, 'and Earth has nothing to do with it, except that it gets wiped out, too.' 'How-how does the Universe end?' said Billy. 'We blow it up, experimenting with new fuels for our flying saucers. A Tralfamadorian test pilot presses a starter button, and the whole Universe disappears.' So it goes. "If You know this," said Billy, 'isn't there some way you can prevent it? Can't you keep the pilot from pressing the button?' 'He has always pressed it, and he always will. We always let him and we always will let him. The moment is structured that way.' 'So,' said Billy gropingly, I suppose that the idea of, preventing war on Earth is stupid, too. ' 'Of course.' 'But you do have a peaceful planet here.' 'Today we do. On other days we have wars as horrible as any you've ever seen or read about. There isn't anything we can do about them, so we simply don't look at them. We ignore them. We spend eternity looking at pleasant moments-like today at the zoo. Isn't this a nice moment?' 'Yes.' 'That's one thing Earthlings might learn to do, if they tried hard enough: Ignore the awful times, and concentrate on the good ones.' 'Um,' said Billy Pilgrim. | Kaikki tämä on tapahtunut, suurin piirtein. Ainakin sodasta kertovat kohdat ovat kutakuinkin totta. Kaveri jonka minä tunsin ammuttiin tosiaan Dresdenissä siksi että hän oli ottanut teekannun joka ei ollut hänen. Ja toinen tuttu mies uhkasi tosiaan palkata gangsterit sodan jälkeen ampumaan hänen henkilökohtaiset vihamiehensä. Ja niin edespäin. Olen muuttanut kaikki nimet. Minä tosiaan kävin Dresdenissä Guggenheimin säätiön rahoilla (Jumalan siunausta niille) vuonna 1967. Se näytti aika lailla samanlaiselta kuin Dayton, Ohio, oli vain vielä enemmän avointa tilaa kuin Daytonissa. Siellä oli jauhautuneita ihmisluita maassa varmasti tonnikaupalla. Kävin siellä vanhan sotakaverini Bernard V. O'Haren kanssa, ja me tutustuimme taksinkuljettajaan, joka vei meidät siihen samaan teurastuslaitokseen minne meidät oli lukittu yöksi silloin kun olimme sotavankeja. Hänen nimensä oli Gerhard Müller. Hän kertoi olleensa jonkin aikaa amerikkalaisten vankina. Me kysyimme millaista oli asua kommunistisessa maassa, ja hän sanoi että aluksi se oli ollut hirveää, kun kaikkien täytyi tehdä lujasti työtä ja kun ei ollut kunnon kattoa pään päälle eikä ruokaa ja vaatteita. Mutta nyt oli jo paremmin. Hänellä oli mukava pikku huoneisto ja hänen tyttärensä sai erinomaista kouluopetusta. Hänen äitinsä paloi tuhkaksi Dresdenin tulimyrskyssä. Niin se käy. Hän lähetti O'Harelle joulun aikoihin kortin, ja näin siinä sanottiin: »Toivotan sinulle ja perheellesi myös ja ystävällesi Hauskaa Joulua ja onnellista Uutta Vuotta ja toivon että me tapaamme uudelleen maailmassa jossa rauha ja vapaus vallitsevat minun taksissani jos vahinko niin tahtoo.« Minä pidän kovasti tuosta: »Jos vahinko niin tahtoo.« En halua kertoa teille mitä tämä vaivainen pikku kirja on maksanut minulle rahaa ja tuskittelua ja aikaa. Kun kaksikymmentäkolme vuotta sitten palasin toisesta maailmansodasta kotiin, luulin että minun olisi helppo kirjoittaa Dresdenin hävityksestä, koska minun ei tarvinnut muuta kuin selostaa mitä olin nähnyt. Ja luulin myös, että siitä tulisi mestariteos tai ainakin että se tuottaisi minulle paljon rahaa, koska aihe oli niin suuri. Mutta minusta ei lähtenyt irti montakaan sanaa Dresdenistä silloin – ei ainakaan kirjaksi asti. Eikä minusta lähde monta sanaa nytkään, kun minusta on tullut vanha äijänkäppänä jolla on muistonsa ja Pall Mallinsa ja jonka pojat ovat aikuisia. Ajattelen miten hyödytön muistini Dresdeniä koskeva osa on ollut ja miten houkuttelevaa on silti ollut kirjoittaa Dresdenistä, ja mieleeni muistuu tunnettu limerikki: Oli nuorimies Amerikan Lapista, joka kalulleen näin alkoi napista: »Kaikki varani veit, minut sairaaksi teit, ja nyt et tippaakaan tiristä tapista.« Ja mieleen tulee myös se laulu joka kuuluu: Yon Yonson on nimeni, Wisconsin on kotini, olen työssä sahalla siellä. Ja kun ihmiset kadulla vastaani tulevat, he kysyvät mikä nimeni on. Ja minä vastaan: »Yon Yonson on nimeni, Wisconsin on kotini...« Ja niin edespäin, loputtomiin. Vuosien mittaan tapaamani ihmiset ovat usein kysyneet mitä minulla on tekeillä, ja tavallisesti olen vastannut, että tärkein työ on Dresdeniä käsittelevä kirja. Sanoin kerran niin Harrison Starrille, sille filmintekijälle, ja hän kohotti kulmiaan ja kysyi: »Onko se sodanvastainen kirja?« »On«, minä sanoin. »Eiköhän.« »Tiedätkö mitä minä sanon, kun kuulen jonkun kirjoittavan sodanvastaista kirjaa?« »En. Mitä sinä sitten sanot, Harrison Starr?« »Minä sanon: Mikset yhtä hyvin kirjoita jääkaudenvastaista kirjaa?« Hän tietysti tarkoitti, että sotia on aina, että ne on yhtä helppo pysäyttää kuin jääkaudet. Uskon minä siihenkin. Ja vaikkeivät sodat tulisikaan väistämättöminä kuin jääkaudet, jäljellä on aina silkka vanha tuttu kuolema. * Pari viikkoa sen jälkeen kun olin soittanut vanhalle sotakaverilleni Bernard V. O'Harelle minä tosiaan menin häntä tapaamaan. Sen täytyi olla vuonna 1964 tai niillä main – New Yorkin maailmannäyttelyn vuotena, mikä se sitten olikin. Eheu, fugaces labuntur anni. Youn Yonson on nimeni. Oli nuorimies Amerikan Lapista. [...] Ja aurinko laski, ja me söimme päivällistä italialaisessa ravintolassa, ja sitten minä koputin Bernard V. O'Haren kauniin kivitalon oveen. Kädessäni oli pullo irlantilaista viskiä kuin ruokakello. Tapasin hänen sievän vaimonsa, Maryn, jolle omistan tämän kirjan. Omistan sen myös Gerhard Müllerille, sille dresdeniläiselle taksinkuljettajalle. Mary O'Hare on sairaanhoitajatar, mikä on hieno ammatti naiselle. [...] Ja siinä ne muistot sitten suunnilleen olivatkin, ja Mary kolisteli yhä. Lopulta hän tuli taas keittiöön hakemaan lisä Coca-Colaa. Hän otti jääkaapista uuden jäätarjottimen, paiskasi sen pesualtaaseen, vaikka jäitä oli esillä vielä vaikka kuinka. Sitten hän kääntyi minuun päin, antoi minun nähdä miten vihainen oli ja että viha kohdistui minuun. Hän oli puhunut itsekseen, joten se mitä hän sanoi oli sirpale paljon pitemmästä keskustelusta. »Te olitte pelkkiä lapsia silloin!« hän sanoi. »Mitä?« minä sanoin. »Te olitte pelkkiä lapsia sodassa – sellaisia kuin nuo tuolla yläkerrassa!« Nyökkäsin että tämä oli totta. Me tosiaan olimme olleet tyhmiä ja kokemattomia sodassa, lapsuutemme lopussa. »Mutta et sinä siitä kylläkään sillä tavoin aio kirjoittaa.« Tämä ei ollut kysymys. Se oli syytös. »En – en tiedä«, minä sanoin. »Mutta minä tiedän«, hän sanoi. »Sinä uskottelet että te olitte miehiä ettekä lapsia, ja elokuvassa sinua näyttelee Frank Sinatra ja John Wayne tai joku muu noista komeista, sotaintoisista, saastaisista vanhoista miehistä. Ja sota näyttää olevan niin suurenmoista, joten me saamme niitä paljon lisää. Ja niissä sotivat lapset, sellaiset kuin nuo tuolla yläkerrassa.« Ja niin minä ymmärsin. Sota häntä niin vihastutti. Hän ei halunnut omien lapsiensa eikä kenenkään muunkaan lapsien kuolevan sodissa. Ja hän ajatteli että sotia osittain edistettiin kirjoilla ja elokuvilla. Joten minä kohotin oikean käteni ja annoin hänelle lupauksen: »Mary«, minä sanoin, »en usko että tämä kirjani koskaan valmistuu. Olen tähän mennessä kirjoittanut varmasti viisituhatta sivua ja heittänyt ne kaikki pois. Mutta jos koskaan saan sen valmiiksi, annan sinulle kunniasanani: siinä ei tule olemaan roolia Frank Sinatralle eikä John Waynelle.« »Tiedätkös mitä«, minä sanoin, »annan sille nimeksi 'Lasten ristiretki'.« Sen jälkeen hän oli ystäväni. *** Billy katsoi kaasu-uunin päällä olevaa kelloa. Hänen oli saatava kulumaan vielä tunti ennen lautasen tuloa. Hän meni olohuoneeseen, heilutti pulloa kuin ruokakelloa, avasi television. Hän joutui hiukan ajassa irralleen, näki myöhäisfilmin takaperin ja sitten jälleen etuperin. Elokuva kertoi amerikkalaisista pommikoneista toisessa maailmansodassa ja niistä urheista miehistä jotka niillä lenisivät. Billyn takaperin näkemä tarina oli seuraavanlainen: Amerikkalaiset koneet, täynnä reikiä ja haavoittuneita ja kuolleita, nousivat perä edellä Englannista sijaitsevalta lentokentältä. Ranskan yllä muutamat saksalaiset hävittäjät lensivät niitä kohti takaperin, imivät luoteja ja kranaatinsirpaleita pommikoneista ja niiden miehistöstä. Samoin ne tekivät maassa oleville rikkinäisille amerikkalaisille koneille, ja nuo koneet nousivat takaperin ilmaan ja liittyivät muodostelmaan. Muodostelma lensi perä edellä yli Saksan kaupungin, joka oli liekeissä. Pommittajat avasivat pommiluukkunsa, panivat käyntiin ihmeellisen magnetismin, joka kutisti liekit, keräsi ne lieriön muotoisiin terässäiliöihin ja nosti säiliöt koneiden vatsaan. Säiliöt varastoitiin siististi telineisiin. Maassa oli saksalaisilla omia ihmeellisiä laitteita, jotka olivat pitkiä teräsputkia. Niillä he imivät pommikoneista ja miehistä pois lisää sirpaleita. Mutta vielä oli jäljellä muutamia haavoittuneita amerikkalaisia, ja jotkut koneet olivat pahasti korjauksen tarpeessa. Ranskan yllä tulivat kuitenkin taas saksalaiset hävittäjät paikalle ja paikkasivat miehet ja koneet täyteen kuntoon. Kun pommikoneet pääsivät tukikohtaansa, teräslieriöt otettiin telineistä ja laivattiin Amerikan Yhdysvaltoihin, missä tehtaat toimivat yötä päivää, purkivat lieriöitä, erottivat niiden vaarallisen sisällön mineraaleiksi. Liikuttavaa kylläkin, tätä työtä tekivät pääasiassa naiset. Sitten mineraalit toimitettiin kaukaisilla seuduilla oleville asiantuntijoille. Heidän tehtävänsä oli panna ne maahan, piilottaa ne taitavasti, niin että ne eivät enää koskaan aiheuttaisi vahinkoa kenellekään. Amerikkalaiset lentäjät luovuttivat univormunsa, muuttuivat koululaisiksi. Ja Hitler muuttui vauvaksi, Billy Pilgrim otaksui. Sitä ei ollut filmissä. Billy vain päätteli. Kaikki muuttuivat vauvoiksi, ja koko ihmiskunta, poikkeuksetta, muodosti biologisen salaliiton, jonka tehtävänä oli aikaansaada kaksi täydellistä ihmistä, nimeltä Aadam ja Eeva, hän oletti. *** Jälleen kului kuukausi ilman välikohtauksia, ja sitten Billy kirjoitti Iliumin News Leaderin yleisönosastoon kirjeen, jonka lehti julkaisi. Kirje kuvasi Tralfamadoren olentoja. Kirjeessä sanottiin, että he olivat kuudenkymmenen sentin mittaisia ja vihreitä ja muodoltaan kuin imupumppuja. Heidän imukuppinsa olivat maata vasten ja heidän vartensa, jotka olivat äärettömän taipuisat, osoittivat tavallisesti kohti taivasta. Varren päässä oli pieni käsi, jonka kämmenpuolella oli vihreä silmä. Olennon olivat ystävällisiä ja he kykenivät näkemään neljässä ulottuvuudessa. He säälivät Maan asukkaita, koska nämä näkivät vain kolmessa. *** Billy luuli että tralfamadorelaiset olisivat ymmällään ja pelästyksissään kaikkien sotien ja murhan muiden muotojen vuoksi, joita Maassa oli. Hän luuli että he pelkäisivät Maan asukkaiden verenhimoisuuden ja hämmästyttävien aseiden yhdessä saattavan lopulta tuhota osittain tai ehkä täysinkin koko muun, viattoman maailmankaikkeuden. Tieteisromaanit olivat saaneet hänet luulemaan sellaista. Mutta sota ei tullut puheeksi, ennen kuin Billy mainitsi siitä itse. Joku eläintarhan yleisöstä kysyi häneltä oppaan välityksellä, mikä oli arvokkainta mitä hän Tralfamadoressa toistaiseksi oli oppinut, ja Billy vastasi: »Se miten kokonaisen planeetan asukkaat voivat elää rauhassa! Kuten tiedätte, minä olen planeetalta jossa on harjoitettu mieletöntä teurastusta aikojen alusta saakka. Minä itse olen nähnyt ruumiina koulutyttöjä, jotka minun omat maanmieheni olivat keittäneet elävältä eräässä vesitornissa; ja siihen aikaan maanmieheni olivat ylpeitä siitä että taistelivat puhdasta pahuutta vastaan.« Tämä oli totta. Billy näki nuo keitetyt ruumiit Dresdenissä. »Ja minä olen vankileireissä yöllä valaissut tietäni kynttilöillä, jotka oli tehty ihmisen rasvasta, ihmisten jotka noiden keitettyjen koulutyttöjen veljet ja isät olivat teurastaneet. Maan asukkaidenhan täytyy olla maailmankaikkeuden kauhu! Elleivät toiset planeetat vielä ole maan taholta vaarassa, niin pian ovat. Kertokaa siis minulle salaisuutenne, jotta voin viedä sen mukanani Maahan ja pelastaa meidät kaikki: kuinka voi planeetta elää rauhassa?« Billy koki puhuneensa komeasti. Hän oli ällistynyt nähdessään, että tralfamadorelaiset peittivät silmänsä sulkien pikku kätensä. Hän tiesi kokemuksesta mitä tämä tarkoitti: hän oli typerä. »Voisitteko – voisitteko sanoa – » hän sanoi oppaalle hyvin nolona, »mikä siinä oli niin typerää?« »Me tiedämme kuinka maailmankaikkeus päättyy – « sanoi opas, »eikä Maalla ole siihen mitään osuutta, paitsi että sekin pyyhkiytyy pois.« »Kuinka – kuinka maailmankaikkeus sitten loppuu?« sanoi Billy. »Me räjäytämme sen kokeillessamme lentävien lautastemme uusia polttoaineita. Eräs tralfamadorelainen koelentäjä painaa käynnistintä ja koko maailmankaikkeus katoaa.« Niin se käy. »Jos tiedätte tämän«, sanoi Billy, »ettekö voi sitä jotenkin torjua? Ettekö voi estää lentäjää painamasta nappia?« »Hän on aina painanut sitä ja tulee aina painamaan. Me annamme aina hänen tehdä sen ja tulemme aina antamaan. Hetken rakenne on sellainen.« »Siis«, sanoi Billy haparoivasti, »kai sitten ajatus sotien torjumisesta Maassa on typerä sekin.« »Tietysti.« »Mutta tämä teidän planeettannehan on rauhallinen.« »Tänään se on. Toisina hetkinä meillä on yhtä hirvittäviä sotia kuin mikään mitä olette nähnyt ja mistä olette lukenut. Me emme voi tehdä niille mitään, joten me yksinkertaisesti emme katso niitä. Me olemme kuin niitä ei olisikaan. Me kulutamme ikuisuutta katsomalla miellyttäviä hetkiä – kuten tätä päivää täällä eläintarhassa. Eikö tämä olekin mukava hetki?« »On.« »Siinä on asia jonka Maan asukkaat voisivat oppia, jos he yrittäisivät kyllin tarmokkaasti: olla välittämättä pahoista ajoista ja keskittyä hyviin aikoihin.« »Hm«, sanoi Billy Pilgrim. |